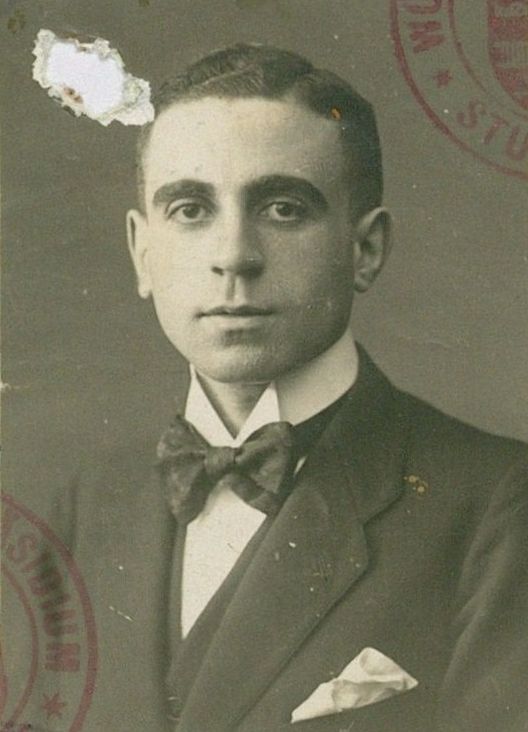

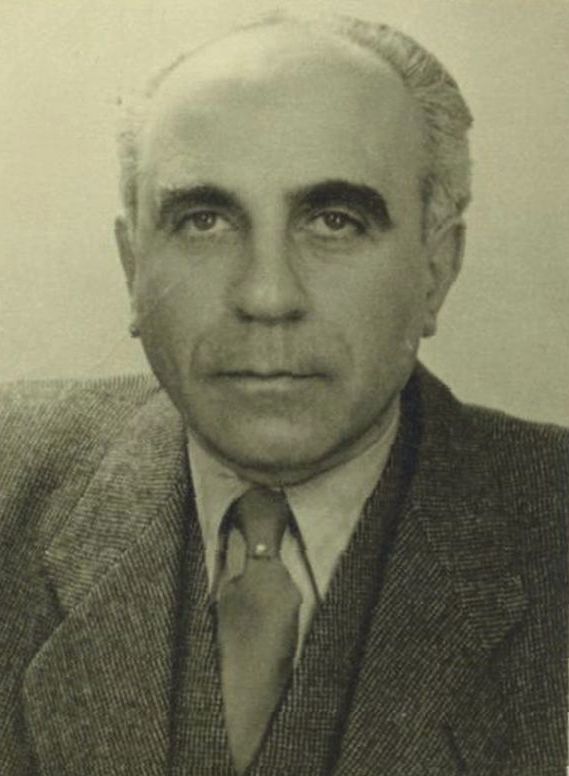

- Dr. med. Max Hommel (1867-1943)

Born on January 5, 1867 in Thalmässing/Bavaria

Murdered in the Ghetto Theresienstadt concentration camp

on January 19, 1943

Interned in Weißenstein in November 1941 - Esther Hommel, geb. Marx (1875-1940)

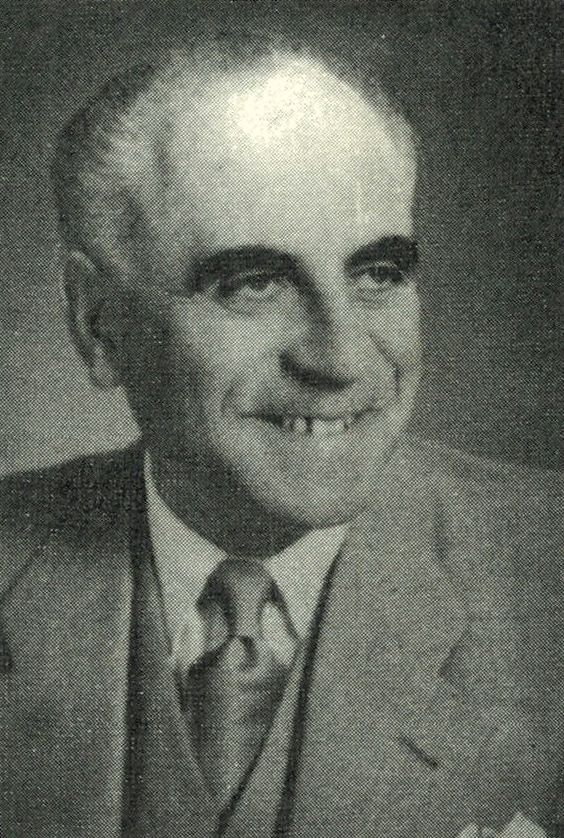

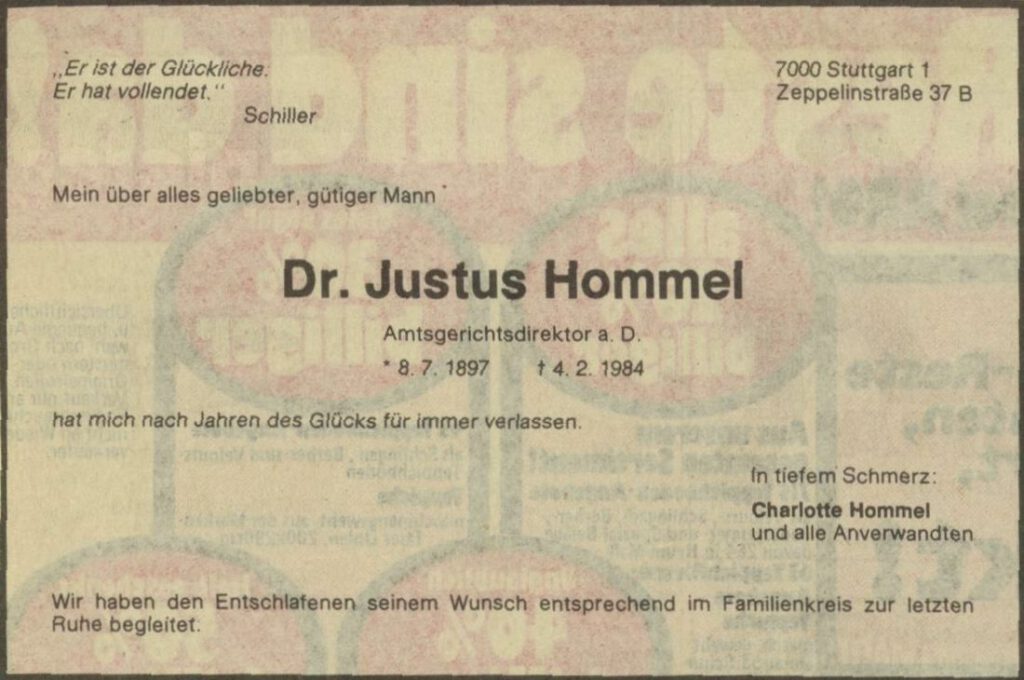

- Dr. jur. Justus Hommel (1897-1984)

Max Hommel’s origins, his youth and student years

The Hommel/Dachauer families in Thalmässing

When Max Hommel was born in Thalmässing, today the district of Roth/Bavarian Middle Franconia, the Jewish population in the town was 17%, or 202 people. There was a synagogue, a Jewish cemetery and a Jewish religious and elementary school here, where his father Samuel Löw (Löb) Hommel had taught since 1864.

(Source: Picture collection Helmut Minderlein, Thalmässing)

Samuel Hommel came from Gersfeld/Hesse and had moved to Thalmässing, where his wife Klara, née Dachauer, came from, whose family was employed by the local Israelite community. The couple’s eight children were born between 1866 and 1878, Max being the second on January 5, 1867. Samuel Löw Hommel was to teach in the town for 48 years and when he retired in 1906, he was given a ceremonial farewell and declared an honorary citizen of the market town. The honored teacher died in Nuremberg in 1912, his wife Klara two years after him in Bad Mergentheim, where their daughter Recha Strauss, née Hommel, lived. Both spouses were buried in Nuremberg. Samuel Hommel was posthumously awarded the Bavarian order ‘Luitpoldkreuz’.

School attendance, studies and military service

Max Hommel must have been a gifted pupil, so that he was the only one of his siblings to attend a grammar school. At the end of 1892, he wrote a curriculum vitae that covers his childhood and youth and also includes the years of his active military service:

Curriculum vitae

I, Max Hommel, wasborn on January 5, 1867 in Thalmässing, k. (k.= royal, author’s note) Bezirksamt Hilpoltstein, in the administrative district of Middle Franconia in Bavaria and belong to the Israelite denomination. My parents, Samuel Hommel and his wife Klara, née Dachauer, live in Thalmässing, where my father is an elementary school teacher. I live in settled financial circumstances, attended the Israelite elementary school in my home town until the age of ten and in the fall of 1877 I was admitted to the Eichstätt school (the Gabrieli-Gymnasium, author’s note), where I was taught for nine years and completed my humanistic grammar school studies in August 1886 with the final examination. In November of the same year, I went to the University of Würzburg to study medicine, attended four semesters of anatomical, physiological and scientific lectures and passed the Tentamen physicum there in August 1888. On October 1 of the same year, I joined the K. (= royal, author’s note) 3rd Jäger Battalion as a one-year volunteer and was discharged on April 1, 1889 as a reserve hospital orderly. From May 1889, I continued my medical studies at Munich University. I spent three semesters there, moved back to Würzburg in the fall of 1890 and passed my licensing examination at the university there on November 27, 1891 with the grade “sufficient”. On February 10, 1892, I received my doctorate in medicine, surgery and obstetrics from the Würzburg Medical Faculty on the basis of my dissertation “Hypertrophic Liver Cirrhosis”. On February 15, 1892, I joined the K. 11th Infantry Regiment as a one-year volunteer doctor in order to complete the second half of my active service, and since August 16, I have been doing a voluntary six-week period of service with the same regiment as a junior doctor in the reserve. As far as my health is concerned, I am of medium height (Max Hommel was 1.64 m tall – author’s note) and medium stature, have never suffered any serious illnesses and enjoy the best of health.

Regensburg, September 26, 1892

Dr. Max Hommel

Reserve junior doctor

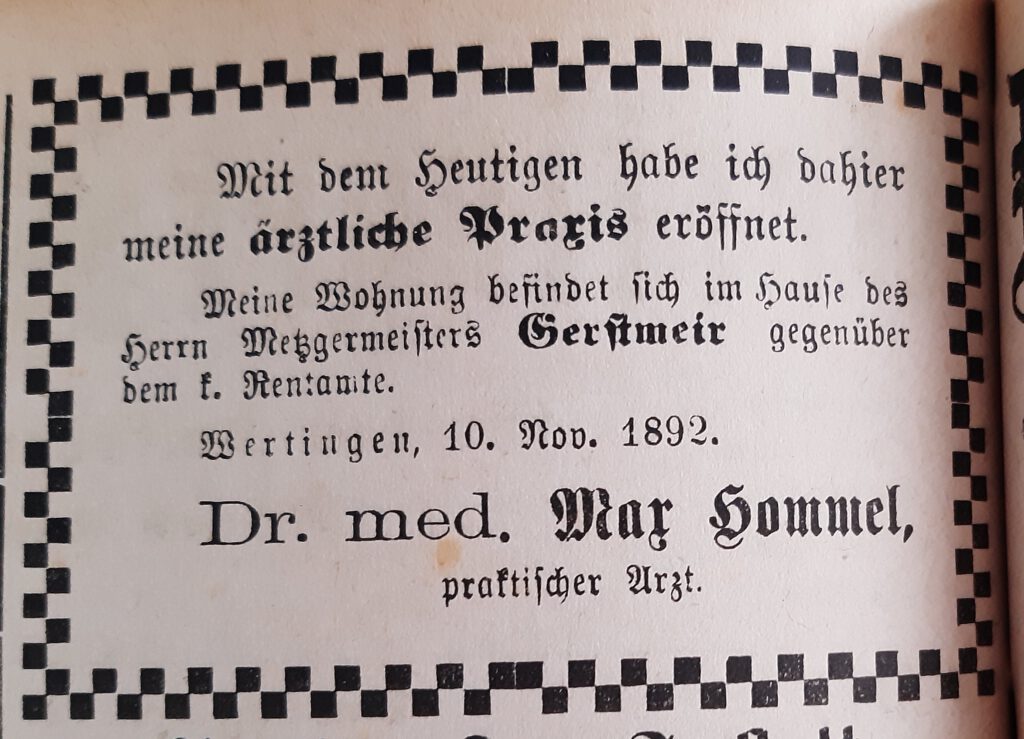

First professional experience in Wertingen and Ichenhausen

Shortly after completing his active military service, Dr. Max Hommel settled in Wertingen/Bavarian Swabia and opened his practice in the house of master butcher Gerstmeir on November 10, 1892.

(Source: Wertingen City Archives)

Wertingen had not had a Jewish population for a long time; Justus Hommel was the first and only Jew to settle there in the 19th century.

After just three years, on May 8, 1895, he said, also documented in a newspaper advertisement, “‘Farewell to all dear friends and patrons …'” and announced his move to Ichenhausen, about 50 km away. It has not been possible to determine what prompted him to move. In contrast to Wertingen – but comparable to Thalmässing – the small town of Ichenhausen in Bavarian Swabia/the district of Günzburg had long been home to a Jewish community. However, the Jewish population in Ichenhausen was significantly larger than that in Thalmässing; in 1890 it amounted to around 27% of the population. A contract between Dr. Hommel, the civic community and the ‘Armenpflegschaftsrat’ (Council for the Care of the Poor) has been recorded from the very beginning of his work. Dr. Hommel undertook to treat servants and the poor of Jewish denomination (free of charge).

Max and Esther start a family

In seiner Zeit in Ichenhausen traf Max Hommel eine wichtige Entscheidung: Am 7. Oktober 1896 heiratete er die acht Jahre jüngere Esther Marx. Sowohl die standesamtliche Trauung als auch die Segnung in der Synagoge fanden aber in Neu-Ulm statt. Trauzeugen waren Esthers Vater Hirsch Marx sowie der Kaufmann Nathan Gerstle, der aus Ichenhausen stammte und in Neu-Ulm wohnhaft war. Zehn Monate nach der Eheschließung konnte sich das junge Paar über sein erstes Kind freuen: Am 8. August 1897 kam ihr Sohn Justus in Ichenhausen auf die Welt, der Vorname erinnert an Max’ jüngsten Bruder, der als Kaufmann in Nürnberg lebte. Als Sohn Justus das Schulalter erreichte, besuchte er die die örtliche Grundschule.

Esther Marx from Freudental

Esther Marx was born on July 14, 1875 in the small Württemberg town of Freudental (then Freudenthal). Her parents were the leather merchant Hirsch Marx and Klara, née Strauß, who came from Berlichingen. Esther had two older and two younger siblings. In 1877, a few weeks after the birth of Esther’s youngest sister, her mother died and Esther had to grow up without her care.

It is surprising that her father Hirsch Marx only married a second time in 1885. Her father’s second marriage to Karoline, née Hess, produced three more children. In 1908, Hirsch Marx moved with his family to Zurich/Switzerland, where he died in 1919. However, Esther was probably lucky in misfortune: Emma Strauß, née Marx, a sister of Esther’s father and her husband Moritz Strauß, Esther’s maternal uncle, who had no children of their own, took in their niece Esther as a foster child. In 1896, the year of her marriage, Esther was still living with her foster parents, who had lived at 10 Moserstrasse in Stuttgart since 1890. Whether Esther received vocational training remains an open question.

When she married Max Hommel, it was Esther’s rich dowry that helped the couple get off to a good start.

26 successful years in Stuttgart

The Hommel family had been registered in Stuttgart since August 25, 1907. In February of that year, Esther’s aunt and foster mother Emma Strauß had died two years after her husband in Stuttgart and Esther inherited her estate. Perhaps this was the reason for the Hommel family to move to Stuttgart. Esther, Max and Justus initially lived on the second floor of the house at Kronenstr. 25, where Dr. Max Hommel also ran his medical practice. In the following years, it became apparent that Dr. Hommel was also active in Stuttgart’s Jewish community alongside his profession: in 1911, he gave a lecture on ‘Judaism and Race’ as part of the Berthold Auerbach Foundation, a topic that was already relevant at the time. From 1915 to 1916, Max Hommel was president of the Stuttgart section of the Jewish lodge ‘Bnei Brith’ (‘Sons of the Covenant’). This lodge was based on the Masonic lodges without belonging to their association. Its aim was to educate people about Judaism and to promote education within its own circle. Even today, right-wing extremist conspiracy theorists consider this lodge to be part of and proof of ‘Jewish world domination’. Dr. Hommel’s membership of the Jewish Community Board, an office he held from 1924 onwards, must also have taken up a lot of his time; he was re-elected in 1932. He was also a member of the administrative board of the Jewish nurses’ home in Stuttgart.

From the summer of 1918, the family’s home and practice were located at Schloßstr. 47.

Co-tenants in the newly built townhouse were a dentist, a colonel, a pastor’s widow and a retired prelate – a middle-class neighborhood! The 1920 address book shows that Dr. Hommel was available in his practice on weekdays from 2 – 3.30 pm and on Sundays from 10 – 11 am. Such short office hours were not unusual for general practitioners at the time; they probably spent most of their working hours making house calls. Saturday is not mentioned in 1920; Dr. Hommel probably observed the Sabbath rest at that time. The consultation hours in 1933 were different, as he was also available on Saturday mornings. The Hommel family lived in/used a 6-room apartment with adjoining rooms on the second floor of the house, which was destroyed in the bombing in 1944. The ‘genuine’ Biedermeier furniture, which Esther Hommel had inherited from her foster parents, must have been the jewel in the living room. As was to be expected in the upper middle classes, the family owned a piano and an extensive library with specialist literature and fine reading. For many years, Rosine Gamper helped Esther Hommel run the household as a domestic servant.

Dr. Max Hommel must have been a well-known and popular doctor, which was also reflected in his income, at least after the years of inflation. In the years before 1933, his annual taxable income averaged 12,000 Reichsmarks. Even in the 1920s, the family income was not enough to finance an apartment and tuition fees for his son Justus at Frankfurt University.

As a German patriot in the First World War

During the First World War, Dr. Max Hommel, like the majority of Jewish Germans, probably considered himself a German patriot. Although Max Hommel was not drafted due to his age, he volunteered his expertise and manpower to the warring German Reich.

Maria Zelzer writes in her book ‘Weg und Schicksal der Stuttgarter Juden’ about the new building of the Jewish Sisters’ Home in Stuttgart’s Dillmannstraße:

“The Board of Directors, with its Chairman Dr. Gustav Feldmann, considered it his duty to put the hospital, which had been completed apart from the interior fittings, and all its nurses at the service of the Fatherland. The new building was offered to the military authorities and in September 1914 it was fully equipped as Auxiliary Hospital VIII in Stuttgart with 30 beds. ( …) The medical management was in the hands of the Stuttgart Jewish doctors Dr. Max Hommel and Dr. Tannhauser, who were later awarded the (Württemberg) Wilhelmskreuz.”

(Source: Ludwigsburg State Archives)

Not enough of an honor: A letter signed by the Württemberg Minister of War, Otto von Marchthaler, dated October 19, 1917. It was addressed to the Royal Bavarian War Ministry/Medical Department. One of Marchthaler’s concerns was the “Promotion of the retired ‘Royal Bavarian Senior Physician of the Landwehr’ Dr. Hommel to staff physician”. The minister argues, “… that although Dr. Hommel is not used in his capacity as a former medical officer in the army service, i.e. he is entrusted with a wartime post, he has made himself worthy of recognition in the form of the requested Most High Proof of Mercy by the fact that he has now volunteered for three years of self-sacrificing service as head physician of the branch hospital “Jewish Nurses’ Home” in Stuttgart”.

Justus Hommel’s career

University studies in Stuttgart, Tübingen and Munich

Justus remained the only child of Esther and Max Hommel and, as we know at least from his father, he was fond of learning. From 1907, he attended the prestigious and historic Eberhard-Ludwigs Gymnasium in Stuttgart.

Die Liste der ehemaligen Schülerinnen und Schüler dieses Gymnasiums liest sich wie eine Aufzählung württembergischer intellektueller Prominenz.

Mit dem Abitur im Juni 1916 verließ Justus diese Schule, die er wahrscheinlich in guter Erinnerung behalten hat. In seinem Abschlusszeugnis wird als geplantes Studium das der ‚Medizin‘ genannt. Der Wunsch seiner Eltern?

Von Herbst 1916 bis Frühjahr 1917 begann er an der Technischen Hochschule Stuttgart ein ‚Studium der allgemeinbildenden Fächer‘, wohl in der berechtigten Annahme, dass er bald zum Kriegsdienst eingezogen werden würde. Tatsächlich musste er als Soldat am 1. Weltkrieg vom 30. Juli 1917 bis zum 15. Januar 1919 teilnehmen, zu seinem Glück aber nicht an der Front.

He later transferred to the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich, where he was enrolled in the summer semester of 1920 and the winter semester of 1920/21. His study book from his time in Munich has survived, which shows which lectures Justus attended: In addition to those in law, he was interested in one on ‘Talmud reading’ and one on ‘History of philosophy in the 19th century’. These are presumably indications of Justus’ interest in religious philosophy topics, on which he would later publish. Munich as a place of study was an embarrassing solution for Justus; here he found what was probably inexpensive accommodation with ‘Heimann’ ‘due to personal connections’, which would not have been the case in his preferred place of study, Frankfurt.

Justus then returned to the University of Tübingen and continued to study law there from the summer semester of 1921 until the winter semester of 1921/22. His leaving certificate is dated 14.03.1922.

(Source: Ludwigsburg State Archives)

In the spring of 1922, he also tried in vain to pass the First Higher Judicial Service Examination here. Although he passed all the examinations in the legal subjects, the Tübingen examination board under Prof. Dr. Carl Johannes Fuchs considered his work in economics to be inadequate. Justus Hommel suspected a political motive behind Fuchs’ attitude: “I had taken a pro-labor stance in my treatment of the subject and it was precisely this work that the (…) chairman of the examination board found fault with, saying that I had ‘politically exploited’ it “.

The rejection of Justus’ work became a political issue when two members of the Reichstag, known to his father Max Hommel, approached the Württemberg Ministry of Justice with a request for a review of the decision. However, the Minister of Justice, Eugen Bolz, did not see himself in a position to do so. He did, however, offer Justus Hommel the privilege of being allowed to repeat his legal clerkship exam in Tübingen, but he refused: “I could not and cannot bring myself to recognize the commission’s decision on my first exam as just by taking a legal clerkship exam in Tübingen without having done so.”

Degree in Frankfurt and professional experience in Stuttgart

However, Justus Hommel’s stance had drastic consequences: “The act of the Tübingen Commission throws me out of the career as a civil servant that I had aspired to and forces me to seek my livelihood in industry as a lawyer or in some other way”. As a replacement for the failed degree, he now sought a doctorate. To do so, he turned to the Faculty of Law at the University of Frankfurt, of which Prof. Dr. Sinzheimer, whom he held in high esteem, was also a member. Justus Hommel was granted an exemption, which was necessary as he did not fulfill the formal requirements (studies at Frankfurt University). His dissertation was probably based on the economics text with which he had failed in Tübingen. The title of the written work, which he submitted on July 2, 1923, was: ‘Das Subintelligendum des § 950 BGB’.

On December 20, 1923, he passed his doctoral examination at Frankfurt University and received his doctoral diploma on January 3, 1924. The names of the reviewers of his thesis are interesting: Hugo Sinzheimer, Hans-Otto de Boor and Friedrich Klausinger. Their very different biographies exemplify the misery of the German lawyers’ guild that soon followed. In the years after the First World War, Frankfurt University had become an open institution, and the (left-wing) ‘Institute for Social Research’ was founded there in 1924.

From August 1, 1923, Justus Hommel, who did not want to be financially dependent on his parents, worked as a trainee at a Stuttgart office for commercial and tax law matters and had the prospect of a managerial position in a Stuttgart company after completing his doctorate. He later wrote about his first years in Stuttgart: “1923 scientific assistant to a Stuttgart business consultant and association managing director, then in-house counsel of a Stuttgart trust bank, then in-house counsel of a Stuttgart electro-industrial company “. He then went into business for himself: from 1925 to 1935, he ran his own office in Stuttgart as a business consultant. His name appears in the Stuttgart address book from 1927 with the job title ‘Syndikus’, his office was located at Paulinenstr. 5, a year later at Friedrichstr. 20, his private residence remained his parents’ apartment in Schloßstraße until his flight in 1935. Justus Hommel’s office address at Friedrichstrasse 20 can be found in the Stuttgart address books under the heading ‘Gewerbe: Volkswirte, beratende und freie Syndici’ in the years 1928 to 1932 inclusive. In a restitution file, Justus Hommel writes that he was known and successful as a business lawyer (‘Wirtschaftsberater’) until 1933. This specialization is not surprising, as he had already concentrated on commercial law during his studies. He also wrote newspaper articles on economic topics and gave public lectures on this subject area.

Humiliation, expulsion, robbery and murder: the Hommel family

during the Nazi era

Justus Hommel: Professional and marriage ban

It is not known how the transfer of power to the Nazis in January 1933 was experienced by the Hommel family. Initially, Justus Hommel was probably the hardest hit: In a restitution file, he writes of being ‘displaced as a business consultant’ after 1933, so that he ‘could not even earn a makeshift living’. Thus, he will have been ‘on his parents’ backs’, a presumably humiliating situation. At this time, however, he still seemed to have hoped to be able to pursue his profession as a lawyer in a different setting: On June 30, 1933, he passed the Württemberg Second State Examination in Law (Große Juristische Staatsprüfung) before the Stuttgart Judicial Examination Commission and planned to open a law firm in the fall of 1933. This never happened. As a ‘Jew’, he was neither admitted to the bar (Nazi decree of April 17, 1934), nor was he appointed as a court assessor (civil service).

In addition, there was his private situation: Justus Hommel had met and fallen in love with Emma Bairle, a merchant’s daughter from Stuttgart who was four years his senior.

In 1924, Emma Bairle had still considered emigrating to North America, but she never did. Emma, who worked as a shorthand typist, bookkeeper and office clerk, belonged to the Catholic Church; what was decisive during the Nazi era, however, was that she was considered an ‘Aryan’ and a relationship with a ‘Jew’ became a criminal offense for both parties after the ‘Nuremberg Laws’ came into force on September 16, 1935 at the latest.

Justus Hommel describes his situation in 1935 in 1946:

“In the summer of the latter year, I was denounced to the Gestapo,

1. because of my relationship with a non-Jewish woman (to whom I was and am engaged),

2. Because of the dictation of allegedly communist texts.

Since the persecution of Jews who had relationships with non-Jewish women also began in Württemberg that summer, I had to leave Germany on July 25, 1935″.

Elsewhere, Justus Hommel names those who had allegedly betrayed him to the Gestapo, including a neighbor of Emma Bairle’s at Vogelsangstr. 32/2.

Max Hommel: involuntary retirement

Max Hommel experienced the professional restrictions later than his son. On January 1, 1938, his license to practice as a ‘Jewish’ doctor was revoked by the Ersatzkassen; however, he was initially allowed to continue practicing due to his ‘services in the First World War’. The financial consequences for him must not have been significant, as he mainly earned his fees from patients who were insured with (state) RVO funds. On October 1, 1938, the Nazi state then banned all ‘Jewish’ doctors from practising their profession and their ‘appointments’ were forcibly terminated. Of the doctors of Jewish origin in Stuttgart, only two were allowed to continue working as ‘Jewish health practitioners’ for ‘Jewish’ patients.

Indications that Max and Esther Hommel’s life was still relatively normal until 1938 are their trips to Switzerland, where they met their son and probably also visited other relatives. Conversely, Nanette Barth, later married Fischhof, a niece of Esther’s living in Zurich/Switzerland, often visited Stuttgart. When it comes to traveling abroad, the question is obvious: Did Max and Esther Hommel consider fleeing Nazi Germany? A sentence by Justus Hommel provides information on this: “My parents did not intend to emigrate”.

Forced relocation to ‘Jews’ houses’

Presumably on November 1, 1938, Esther and Max Hommel had to leave their apartment at Schloßstr. 47, which had been their home for over 20 years. The new address Militärstr. 68 (today Breitscheidstraße) in Stuttgart was a ‘Jews’ house’.

Here, Esther and Max were still able to use a separate 3-room apartment and bring a considerable part of their previous home furnishings with them. In Militärstraße, the Hommels also received a visit from Nanette Barth, whose testimony would become important in the restitution proceedings after 1945. After just nine months, the Hommels had to move again. The owner of the house at 68 Militärstrasse, the Jewish factory owner Oskar Weinschel, had to sell the house to the city of Stuttgart in the course of his flight to the USA, which made it available to ‘Aryan’ tenants.

The large town house at Rosenbergstrasse 103, where Esther and Max Hommel were subsequently forced to live, was built around 1935 and, like the neighboring house at no. 105, belonged to the Jewish factory owner Emanuel ‚Emil‘ Strauss und seiner Frau Rosa.

destroyed in 1943 (Source: Stadtarchiv Stuttgart)

The Hommel couple were also able to use their own 3-room apartment on the 4th floor of this house. Justus reported in the restitution proceedings: “My parents continued their former household in the last apartment in Rosenbergstraße”.

Esther Hommel’s death in 1940

Esther’s death is documented on August 11, 1940; she died of ‘diabetes mellitus’ as a patient in Stuttgart’s Marienhospital. The place was not a matter of course. Susanne Rueß writes in her book ‘Stuttgarter jüdische Ärzte während des Nationalsozialismus’ p. 38: “The admission of Jewish patients to Stuttgart hospitals was increasingly boycotted. After the ‘Reichskristallnacht’, all ‘non-Aryans’ were refused hospital treatment. The Catholic Marienhospital in Stuttgart and the Robert Bosch Hospital disregarded the existing regulations as far as possible and continued to treat Jewish patients.”

Justus Hommel described his mother’s death somewhat differently in 1946:

“My mother (…) was suffering from gallstones. She died on August 11, 1940 as a result of a sudden biliary suppuration caused by gallstones. The nature of the illness and the sudden onset of the final illness make it highly probable that the cause of the fatal illness was the emotional pressure my mother was under as a Jew at the time.”

Esther Hommel, née Marx, was buried in the Prague Cemetery in Stuttgart.

(Source: Dr. Joachim Hahn)

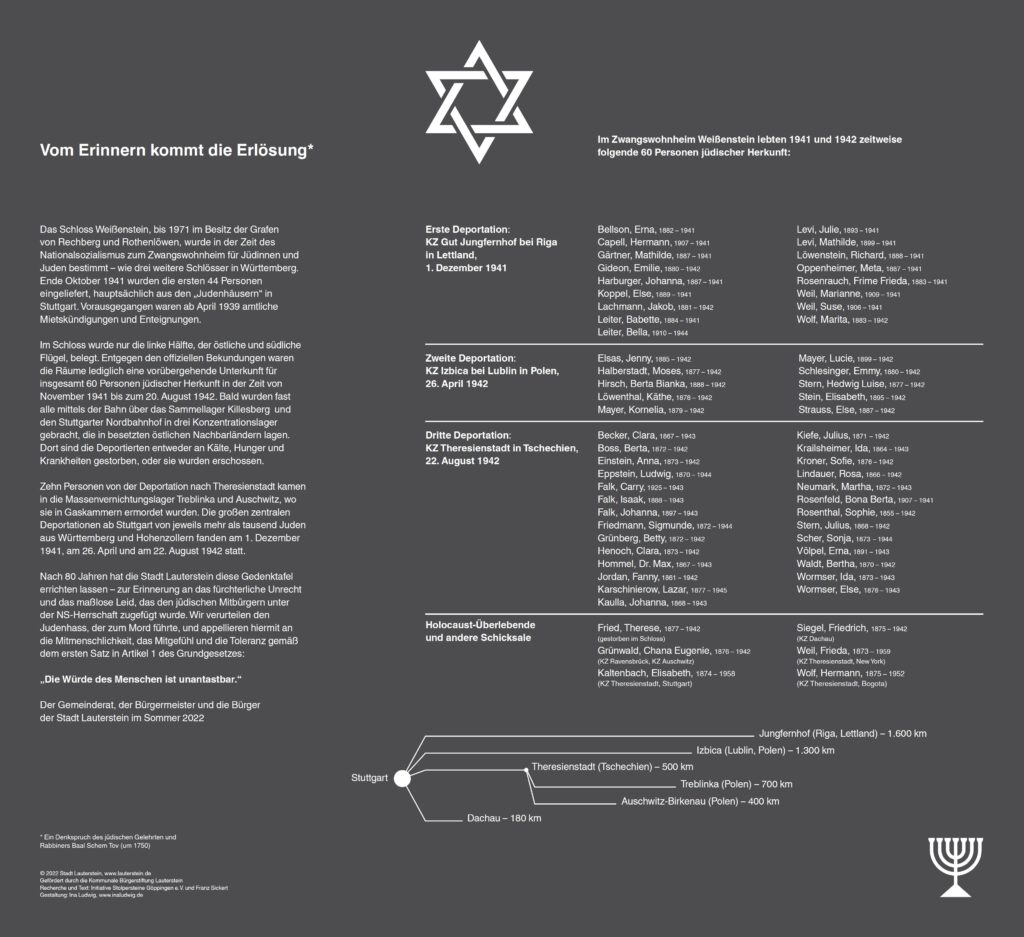

Max Hommel as an internee at Weißenstein Castle

Max Hommel lived alone as a widower in Stuttgart for over a year; from September 19, 1941, he, the once respected doctor and honored citizen, had to wear the discriminatory ‘Jewish star’. In mid-October of that year, he was informed that he would have to leave his Stuttgart apartment in the ‘Jews’ house’ at Rosenbergstrasse 103 on November 1, 1941. In addition to him, the two housemates Else Strauss and Marita Wolf were also forced to move to Weißenstein Castle in the district of Göppingen. A further eight people from the neighboring ‘Jews’ house’ at Rosenbergstrasse 105 were taken to the castle; they too must have been personally known to Dr. Hommel. The largely empty castle in Weißenstein (now part of the town of Lauterstein) had been provisionally prepared to accommodate the initial 45 people.

The housing situation was cramped, at least initially; whether the heating was sufficient in the cold and long winter of 1941/42 is doubtful. The same applies to the food supply. As a 74-year-old, Dr. Hommel was one of the older inmates and the only one with an academic education. Were there any former female patients among the inmates? Dr. Hommel’s medical advice was probably in demand. He was able to take a small part of his Stuttgart furniture with him to the castle; the majority that remained in Stuttgart was taken from him. During his forced stay at the castle, he was able to stay in contact with his son by letter. Dr. Max Hommel was one of the 16 inmates who had to live in the castle from the beginning until it was closed. When he left the castle, his few furnishings were left behind and subsequently auctioned off. The proceeds did not go to the owner, but later to the tax office of the nearby town of Geislingen/Steige: 379 RM.

On August 19, 1942, 27 of the last 28 residents of the forced residence were taken by train to the camp on Stuttgart’s Killesberg. After two terrible nights, a total of 1078 people from Württemberg, Hohenzollern and Baden were deported in primitive Reichsbahn wagons from Stuttgart Nordbahnhof to Theresienstadt concentration camp, where they arrived starving and thirsty at the nearest train station, Bauschowitz, on August 23. Max Hommel’s sister Recha Strauss and her husband Julius were also on the same transport.

The Nazi state paid dearly for the ‘mercy’ of being allowed to ‘live’ in the Theresienstadt concentration camp: through the ‘right to buy a home’. In return, Max Hommel was robbed of 20,000 RM by being deprived of his shareholdings.

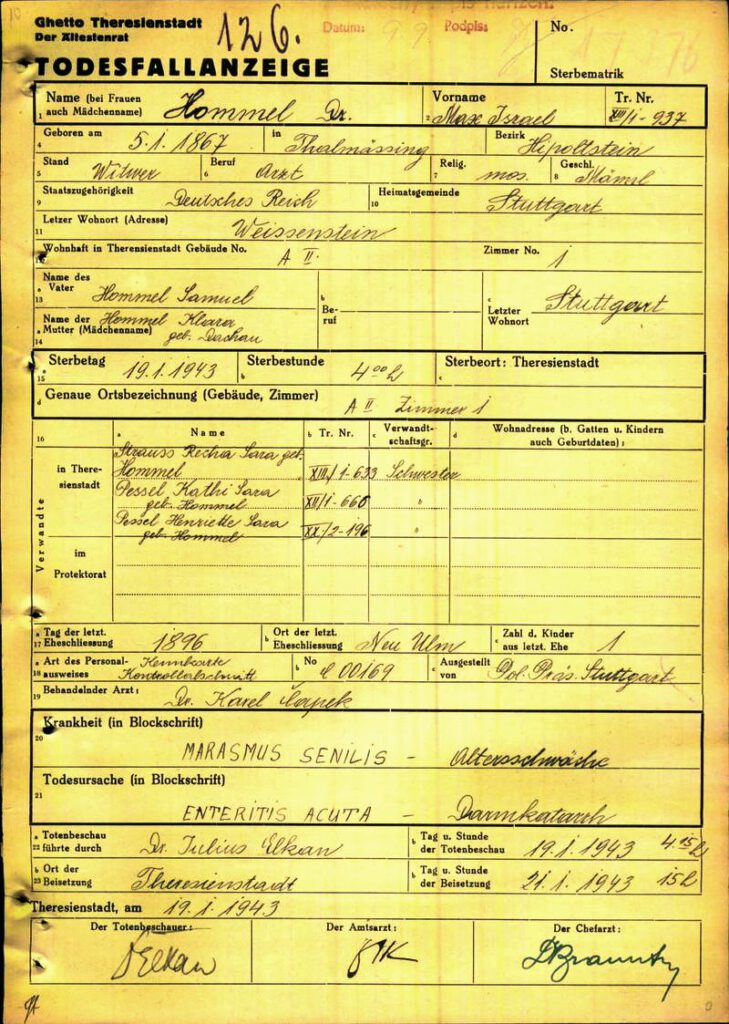

Misery and murder in the Theresienstadt ghetto concentration camp

Max Hommel was sent to Block AII, the former Jäger barracks, where old (male) prisoners had to live. Lack of food, inadequate health care, insufficient hygiene and finally the winter cold of 1942/43 characterized the ‘living’ conditions to which Mr. Hommel was exposed. On December 10, 1942, his sister Kathi Pessel, who was two years younger than him, died in the camp, which Max must have received with great sadness.

Max Hommel survived his sister for barely more than a month. The surviving ‘death notice’ states that ‘Dr. Max Israel Hommel’ died in his ‘room’ at 4 a.m. on 19 January 1943. The Jewish doctors, even prisoners who had to fill out the form, entered ‘old age’ as the illness and ‘intestinal catarrh’ as the cause of death. They were not allowed to write ‘murder’. In a restitution file, son Justus Hommel reported that his father had starved to death in the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Other murdered members of the Hommel and Marx families

Justus Hommel’s life in exile

Switzerland – Italy – Switzerland

After the transfer of power to the Nazis, Justus Hommel realized that he would have no professional future in Nazi Germany. From February to June 1934, he traveled, including to France, to find out where he could emigrate to and set up a business. Finally, he left Stuttgart on July 25, 1935, also to avoid arrest, and traveled to Zurich, presumably on a tourist visa (see above). The related Barth family had been living there for some time; Klara Barth, née Marx, was his mother’s youngest sister.

Justus stayed in the Swiss metropolis until January 1936 without being registered. When his tourist visa expired, he was faced with the question of whether he should stay in Switzerland. Living there as an ’emigrant’ would have meant a ban on work and thus financial dependence on relatives or (Jewish) aid organizations. Switzerland also only saw itself as a ‘transit country’, meaning that those who fled and were assigned a place to stay were only tolerated as long as their onward journey could not be realized. Against this background, it is understandable that Justus left Switzerland and moved to Italy, where around 4,000 German or Austrian Jews were living as refugees until 1938, including the Geschmay family from Göppingen.

Moving to Mussolini’s fascist Italy as a Jewish-German refugee sounds absurd at first. In fact, Italian fascism was not hostile to Jews for a long time, but this was to change in 1938. Justus Hommel spent around 30 months in Italy, where he spoke the local language. On January 20, 1936, he arrived in Bologna, where he stayed for a year and gave lessons at the Berlitz language school. A few months after his arrival, his German passport expired, which is why he had to visit the German consulate in Milan, where his passport was renewed for the last time on March 25, 1936. In Bologna, however, Justus Hommel was unable to earn his own living. Perhaps this was the reason why he moved to Bolzano, where he was registered from January 4, 1937. When Justus Hommel was asked by the clerk in charge of the counter there how long he wanted to stay, he replied: “Forever”. This wish was not fulfilled, but the first attached stamp ‘Temporary’ was later replaced by one with ‘Permanent’.

During his stay in Bolzano, he was able to earn a sufficient income by teaching languages. In 1937, according to his own account, he published in the German-language conservative Catholic newspaper in Bolzano ‚Dolomiten‘ an essay on religious topics. It has not been possible to clarify why Justus Hommel left Bolzano; a surviving correspondence indicates problems with the registration office. The decisive factor for him was probably the racist and anti-Jewish turnaround in Italy from July 1938, which was to be followed in September of that year by the order to expel ‘foreign Jews’ by the end of the year. Justus Hommel anticipated this: on July 11, 1938, he traveled back to Switzerland, specifically to Lucerne, where he was probably assigned a place of residence. He lived at various addresses in the central Swiss city for around two years. There he came into contact with Rudolf Rößler, the co-publisher of the anti-fascist, yet religiously oriented Lucerne-based Vita Nova publishing house, where Justus Hommel’s first book was to be published. It is astonishing that he was allowed to publish in Switzerland as a German emigrant. He was helped to survive by grants from the ‘Association of Swiss Jewish Refugee Aid’, which were granted from October 7, 1938 to December 1, 1942. As Justus Hommel – a stateless person since 1939 – was living in Lucerne, the University of Frankfurt revoked his doctorate on February 6, 1940. Justus Hommel was probably unaware of this nasty gesture and continued to sign with the title he had acquired. It was not until three years after his death, in 1987, that Frankfurt University came to its senses and declared the withdrawal of his doctorate to be unlawful.

In search of religious certainty

It is said that Justus Hommel began to grapple with questions of ethics, religion and faith as early as the beginning of his exile in Switzerland in 1936. He immersed himself in theological thought processes and subsequently turned away more and more from the Israelite faith of his family of origin. It is not known how his parents felt about this; it is also unclear whether his encounter with his fiancée, the Catholic Emma Bairle, contributed to his religious reorientation. Justus Hommel’s book ‘Fürwort der Religion’, published by Vita Nova in 1942, was the result of his ‘search’ and can be read as a declaration of faith in Catholicism.

In Swiss labor camps

From June 1940 until the end of November 1942, Justus Hommel was required to perform forced labor for Switzerland. This could be considered coercion, as he would have faced imprisonment and/or deportation to Germany if he refused. He shared his fate with many (often Jewish) emigrants and refugees from Germany and Austria. He was interned in the Swiss labor camps Felsberg/Graubünden, Sattelegg/Schwyz and for over two years in the school and labor camp in Davesco/Ticino.

Felsberg, which was set up as a camp on April 9, 1940, was the first of its kind in Switzerland and Justus Hommel was one of the emigrants who were registered early on. In both Felsberg and Sattelegg, the internees were obliged to build military roads, which meant hard physical labor. Justus Hommel fell ill in the Davesco camp, which led to his release from the Swiss camp system. As an inmate of a Swiss labor camp, he received a small wage and was able to recuperate on 50 vacation days a year. A few days after he was sent to the Sattelegg labor camp, Justus must have learned of his mother’s death. Circumstances did not allow him to attend her funeral and stand by his father. During the time Justus was interned in the Davesco labor camp, his father lived as a prisoner in Weißenstein Castle.

After his release from the Davesco camp at the end of November 1942, Justus Hommel lived in Zurich until the end of April 1943, but spent the rest of his exile in Lucerne, which he was not allowed to leave without permission. In 1943, the city authorities there banned Jewish refugees and emigrants from staying on the popular Quai area and the bridge – the local population felt harassed. As the defeat of Nazi Germany loomed, the Swiss authorities wondered what the emigrants/refugees would think and say about their time in Switzerland. One result of this reflection were offers of professional qualifications, to which Justus Hommel was also invited: He took part in a short legal training course in 1945, for example, which was held in Zurich. Towards the end of the war, Justus Hommel also joined two emigrant associations in Switzerland: The ‘Free Germany’ movement and the ‘Protection Association of German Writers in Switzerland’. Incidentally, the Swiss authorities wanted to force all (Jewish) emigrants and refugees out of the country as quickly as possible. There were other reasons why Justus Hommel also wanted to leave the country as soon as possible.

Justus Hommel’s new beginning in post-war Germany

A marriage made up, a new denomination

Justus Hommel wanted to return to Stuttgart immediately after the end of the war, but the American military administration did not allow him to do so. It was only after a year, on May 16, 1946, that he arrived in his home town. ‘Hometown? There was probably a decisive reason why he was drawn to Stuttgart despite all of this: he had barely arrived, on June 3, 1946, when he married his fiancée of many years, Emma Bairle, and the church-Catholic wedding took place on December 17.

Eleven years of life together had been robbed from the couple, and now that they were finally together, it was too late for children, Emma was already 53 years old. The couple’s first apartment was on Rosenbergplatz, where they lived as subtenants. Of course, there was no happy togetherness; Emma’s old mother, who had lost her apartment in the bombing, lived with them until her death at the end of 1948.

Catholic wedding? Yes, because in the same year, 1946, Justus Hommel had fulfilled another wish: He, who had previously described himself as ‘freireligious’, took convert lessons from the Catholic priest Carl Küven from the Stuttgart parish of St. Elisabeth, with the result that the Rottenburg Episcopal Ordinariate approved Justus Hommel’s admission to the Catholic Church on November 29, 1946.

(Source: Stuttgart State Archives)

Activities at the trial chambers and in the VVN

Justus Hommel had returned from Switzerland penniless, his stolen property and inheritance were still far from being available and in the first few months the couple lived on Emma’s income alone. Justus therefore had to and wanted to work and – obviously – in his trained profession as a lawyer. In June of that year, he applied to work in an appeals chamber of the trial courts. After the Nazi era, there were very few lawyers who had not served the Nazi regime; it was therefore no coincidence that Gottlob Kamm, Minister of Liberation in Württemberg, wrote to the Stuttgart military government at the beginning of July 1946: “I intend to appoint Dr. Hommel as chairman of an appeal chamber in Stuttgart”. Hommel as chairman of an appeal chamber in Stuttgart”. From September 5, 1946, Justus Hommel became chairman of the appeal chamber at the Stuttgart-Untertürkheim appeal chamber, not quite in accordance with his wishes.

In the months that followed, the Württemberg Ministry of Labour ultimately tried in vain to poach Justus Hommel, who specialized in commercial law, from the Ministry of Liberation. For a short time, Justus Hommel held the title of President of the State Labor Court, but he did not exercise this office; he resumed his activities within the Ministry of Liberation and became ‘Managing Chairman of the Appeals Chamber’ on December 15, 1946; in January 1947, his title was modified to ‘President of the Appeals Chamber’.

Justus Hommel found himself in various conflict situations during his dedicated performance of his duties. In August 1948, for example, a complaint was lodged against him after he had two witnesses detained for three hours in appeal proceedings. Subsequent proceedings for deprivation of liberty were discontinued at the end of 1948 and he returned to his post after a short leave of absence. His ‘most prominent case’ was probably the appeal proceedings of the former Nazi mayor of Stuttgart, Karl Strölin. At the end of 1949, the trial chamber institutions were dissolved and Justus Hommel’s first phase as a lawyer in post-war Germany came to an end.

It should be added that he was also admitted to the Stuttgart bar from September 25, 1946 to December 31, 1949, but did not practice this profession. From January 1, 1950 to April 4, 1951, Justus Hommel was temporarily unemployed. He applied for the consular service in the spring of 1950 without even receiving a reply. He saw this rejection as an indication of an impending “neo-Nazi Germany, as rightly seen abroad”.

Consequently, he had been a member of the VVN (Association of Persecutees of the Nazi Regime) since 1946 and used the time without a job to volunteer for the VVN. He advised on legal matters and, for example, formulated – apparently successfully – demands for the upcoming pension ordinance in 1950. This makes his resignation from the VVN on September 20, 1950 all the more surprising. Justus Hommel justified his resignation by stating that “one of its groups was dominating” within the association – without giving any further details about this “group”.

In fact, the percentage of persecutees from the communist resistance increased over the years since 1945, so that by 1950 they had become the largest group within the VVN in terms of numbers. The background to this development was the beginning of the ‘Cold War’ between the Western powers and the Soviet Union. Both the CDU (whose most prominent VVN member was initially Konrad Adenauer) and the SPD had put pressure on their party members to leave the VVN; cooperation with communists persecuted during the Nazi era was undesirable. As a result, many non-communist persecutees left the VVN, which was accused of being a sub-organization of the KPD (= Communist Party of Germany), which had been banned since 1956. According to the ‘Adenauer Decree’, those who remained loyal to the organization had to fear that they would not receive employment with the state. Justus Hommel was also threatened with this fate and presumably drew the consequences.

Restitution: Justus seeks compensation and restitution of his family’s stolen property

Shortly after his return to Germany, Justus Hommel sought financial restitution for the looted family property. As a trained lawyer, he decided not to be represented, as was usual in restitution cases. While he was still able to prove his parents’ financial investments, the value of his mother’s home furnishings and jewelry became a matter of dispute. His ‘opponent’, the German state, represented by the State Office for Restitution, also behaved as restrictively as usual towards Justus Hommel. Justus Hommel probably considered the offered result of the negotiations (decision of the Higher Regional Court of Stuttgart of February 25, 1956) to be inappropriate, as he filed an application for review with the Supreme Restitution Court in Nuremberg in 1957. However, this application was rejected.

The proceedings for compensation for economic losses caused by persecution (loss of income for him and his father) and for professional advancement proceeded without comparable problems. However, the German state refused to pay Justus Hommel compensation for his time as a forced laborer in Switzerland.

As a lawyer in the (Baden-)Württemberg civil service

From April 1951 to November 1, 1960, Dr. Justus Hommel worked as a public prosecutor at the Stuttgart public prosecutor’s office. From December 1, 1960 to October 31, 1963, he was a district court judge and later a senior district court judge, presiding over a court of lay judges at Stuttgart District Court. His last title, which was awarded to him on an honorary basis, was that of ‘Amtsgerichtsdirektor i.R.’. In 1964, immediately after his retirement, Justus Hommel worked part-time as a court clerk for the Stuttgart State Office for Restitution for just under a year.

Justus Hommel was one of the few Stuttgart lawyers of Jewish origin who entered the civil service in Stuttgart after the end of Nazi rule. Alfred Marx (1899-1988), a fellow student of Justus Hommel’s at the University of Tübingen, is well known among them. In 1965, Marx published the text „Das Schicksal der jüdischen Juristen in Württemberg und Hohenzollern 1933 – 1945“, in which Justus Hommel’s life is also briefly described.

Im Ruhestand

Die gewonnene Zeit im Ruhestand nutzte Justus Hommel als Schriftsteller für sein religionsphilosophisches ‚Lebensthema’: Im Jahr 1971, 29 Jahre nach ‚Das Fürwort der Religion‘, erschien sein zweites Buch, dessen Titel ‚Umkämpfter Glaube‘ lautet, und im Jahr 1976 veröffentlichte er zwei Bücher: ‚Auferstehung und Transparenz’ sowie den als Abschluss der Reihe gedachten Titel ‚Der „souveräne“ Mensch?‘.

Justus Hommel is likely to have seen himself as an outsider in Stuttgart’s intellectual circles: As a convinced Catholic Christian among mostly Protestant Christians, as a Christian among agnostics or atheists who were active in the Max Bense Circle beyond Stuttgart. He saw his ability to believe as a gift, just as other people can open themselves to music – or not. In March 1979, Justus’ wife Emma Hommel died and was buried in the Prague cemetery. Two months later, Justus Hommel, now 82 years old, married Charlotte Conzmann, a Protestant who was 24 years his junior. It is possible that Justus Hommel had known the Stuttgart-born woman for decades, as in the years 1947-48 the trained teacher worked for the Ministry of Liberation, as he did, but in her case in the administrative sector.

Justus Hommel’s estate

Dr. Justus Hommel, who last lived at Zeppelinstr. 37B in Stuttgart, died on February 4, 1984 in Stuttgart’s Diakonie-Klinikum and was buried in the grave of his first wife Emma in Stuttgart’s Pragfriedhof cemetery.

Charlotte Hommel died in September 1990; her grave, which has since been closed, was also in the Prague cemetery.

After Justus Hommel’s death, on July 3, 1984, his widow Charlotte established the ‘Justus Hommel Foundation’, endowed with 10,000 DM, at Stuttgart’s Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium, where Justus had graduated in 1916. The purpose of the foundation reads: “In accordance with the deceased’s detailed wish to preserve the beauty and purity of our German language, the award is to be given to the student who, after passing their school-leaving examination at the Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium, has shown a particularly well-chosen expression of the German language in their essays and lectures.”

Since 2022, a memorial plaque below the castle in Weißenstein/Town of Lauterstein has commemorated the Jews who were interned there, including Dr. Max Hommel.

On November 21, 2025, Gunter Demnig laid Stumbling Stones on Schloßstraße 47 in Stuttgart in memory of the Hommel family.

We would like to thank the city archives of Stuttgart, Neu-Ulm, Ichenhausen, Thalmässing, Wertingen, Dillingen, Tübingen, Zurich and Lucerne, the (historical) registry offices of Stuttgart, Bolzano and Bologna, the university archives of Tübingen, Munich and Frankfurt/Main, the Stuttgart cemetery administration and the diocese of Rottenburg, the Stuttgart Catholic parishes of St. Elisabeth and St. Fidelis, the Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium and its support association, the Bavarian Main State Archives in Munich and the Baden-Württemberg archives of the VVN – Bund Anti-Nazi League. Elisabeth and St. Fidelis, the Eberhard-Ludwigs-Gymnasium and its support association, the Bavarian Main State Archives in Munich and the Baden-Württemberg archives of the VVN – League of Anti-Fascists. Documents were consulted in the Ludwigsburg State Archives, the Stuttgart Main State Archives and the Württemberg State Library in Stuttgart. We were able to draw on the important book publications by Maria Zelzer and Susanne Rueß and we are grateful to Mrs. Irmgard Prommersberger for documenting the Jewish history of Thalmässing, as well as to Mr. Michael Volz from the pkc-Freudental for the information on Esther Hommel’s place of origin and family. Last but not least, we gratefully benefited from Dr. Joachim Hahn’s wealth of knowledge. Janina Pinger from the Göppingen town archives patiently helped us interpret Sütterlin texts. We are happy to substantiate statements in the text with references.

(16.02.2025 kmr)