The displacement of Jews from their homes from 1939 onwards

The establishment of the Forced Residential Home in November 1941 was one of the measures with which the Nazi administrations massively intervened in the lives of Jewish Germans. Already with the ‘Law on Tenancies with Jews’ of April 30, 1939, the ‘legal’ basis for the following injustice had been laid, namely to deny Jewish Germans the free choice of housing.

With the following measures, the Nazi administration pursued several goals: To separate Jewish Germans from non-Jews spatially and socially, to crowd them together in cramped housing units, and to make the housing that became ‘free’ available to ‘Aryans,’ with priority given to the housing needs of armaments workers and their families with the onset of the war. In many cities, non-Jewish landlords had given notice to their Jewish tenants. They could now only find a new apartment in ‘Jewish’ houses, and the ‘Jewish’ house owners had to tolerate the influx. This often resulted in crowded conditions in the ‘Jewish’ houses, which was a deliberate harassment and humiliation.

Existing Jewish institutions were also forced to take in far more people than the space actually allowed, for example at the Jewish old people’s home ‘Wilhelmspflege’ in Sontheim near Heilbronn. In some cases, Jewish institutions were also more or less forcibly rededicated, as in Herrlingen near Ulm, where the Jewish country school home became an old people’s home.

Another coercive measure consisted of forcibly quartering Jewish residents from towns in rural communities where a Jewish population had traditionally lived, for example in Haigerloch.

Finally, (largely empty) derelict castles were misused as forced dormitories for mostly elderly Jewish people. In Württemberg these were the castles of Dellmensingen, Eschenau, Oberstotzingen, Tigerfeld and Weißenstein. Weißenstein Castle, with 60 “resettled” (but only about 40 lived in the castle at the same time), is one of the smaller institutions, but existed longer than others, from the end of October 1941 to August 1942.

Weißenstein Castle in the former town of Weißenstein

Weißenstein, which has been a sub-municipality of the town of Lauterstein since 1974, is located in the east of the district of Goeppingen, which was established in 1938. The town lies about 20 km east of Göppingen in a deeply cut valley of the Swabian Alb. Weißenstein had about 800 inhabitants in 1941 and was characterized by agriculture and forestry, buildings for the local count and the Catholic faith.

In the last, barely democratic Reichstag election of March 5, 1933, 48 % of the votes in Weißenstein went to the Catholic-oriented Center Party, 6 % to the SPD and 45 % to the NSDAP. The fact that the NSDAP did not become the relatively strongest party at that time is exceptional in a Reich-wide comparison.

In Weißenstein there was no established Jewish population in the 20th century. However, Jews were allowed to settle temporarily on the territory of the Lords of Rechberg in the early modern period, unlike in the surrounding Württemberg and Ulm areas. A negatively outstanding event in the local history of Weißenstein was the cruel execution of the Jewish criminal Ansteet in 1553 at the foot of the Galgenberg. Even though the people of Weißenstein had no Jewish neighbors in the village, a personal encounter between non-Jews and Jews was possible, because several Jewish families, including the cattle dealers Lang, lived in the community of Süßen, which was only 11 km away.

In addition: as a ‘climatic health resort’ Weißenstein had also attracted Jewish vacation guests from Stuttgart and the surrounding area since the beginning of the 20th century. The only synagogue in the district stood in Göppingen, but had been destroyed by Nazi gangs in the pogrom night of November 9-10, 1938. The last rabbi from Goeppingen had fled Germany afterwards.

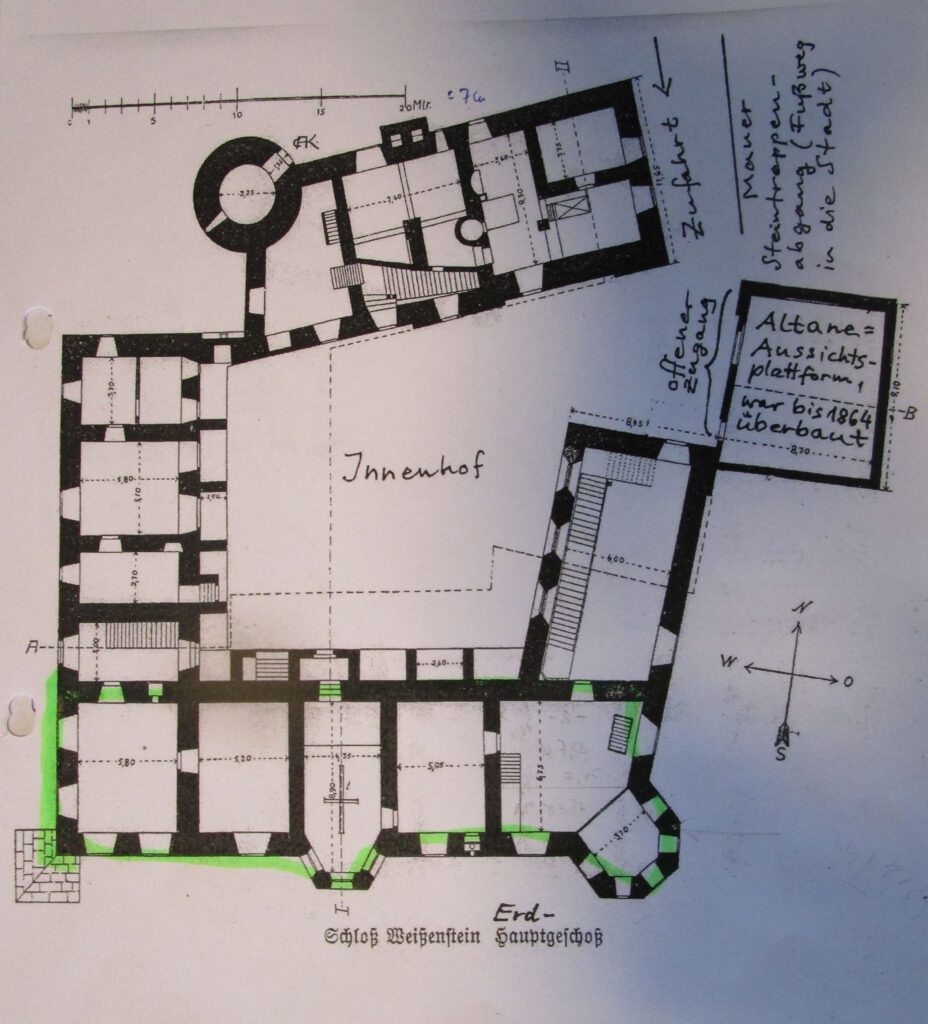

Weißenstein Castle, as it appeared in 1941, was based on extensions and renovations from the 17th and 19th centuries. It is located above the town on the steep hillside on a tuff terrace, which was formed by lime deposition of water from the nearby trout hole (karst spring).

For centuries the castle was in the possession of the noble family(ies) of Rechberg, it was next to the castle Rechberg (since 1865 a ruin) their second ancestral castle, but was not inhabited by the family since the twenties. The Donzdorf castle became the main residence. Until the beginning of the 19th century, the von Rechbergs were also the local lords of Weißenstein and the surrounding area. In 1941, Joseph Graf von Rechberg und Rothenlöwen, who was born in Weißenstein in 1885, was the owner of Weißenstein Castle, other castles, large estates and many agricultural and forest areas in the surrounding area.

Declared a compulsory residence by contract

In the summer of 1941, consultations took place as to whether a ‘residential home’ for Jews could be established in Weißenstein Castle. A meeting in the Count von Rechberg’s Donzdorf castle was attended by: the Count as the owner of Weißenstein Castle, representatives of the Göppingen District Office, the Wuerttemberg Ministry of the Interior, the Gauleitung, the Gestapo, the Hirth Motor Works, and the Weißenstein mayor August Wahl. The advisory board considered (by a majority?) the castle to be suitable. In addition to criteria such as ‘vacant, cheap and without alternative use’, the fact that Weißenstein’s train station was only a good kilometer away from the castle may also have contributed to the selection, since the Nazi state was already planning the deportation and murder of German Jews at that time.

In the Weißenstein council minutes of September 19, 1941, it becomes clear that the town of Weißenstein had to conclude three partial contracts:

- with the Count von Rechberg’s Central Chancellery for the use of the southeast wing of the castle.

- with the Jewish Religious Community of Württemberg e.V. (which was bound by instructions to the Nazi authorities).

- with Hirth – Motoren G.m.b.H Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen.

A fourth, decisive ‘contractual partner’ is not mentioned: The NS – state with its state and party organizations such as Gestapo and SS, which had the last word.

Winners and losers

A short summary of the contracts:

1. The contract of 18.08.1941 between the city of Weißenstein and the Rechberg’sche Zentralkanzlei states: The owner of the castle, the Rechberg’sche Zentralkanzlei receives from the city of Weißenstein a comparatively small rent of 600 Reichsmark (RM) per year. This becomes clear if one compares this amount with the approx. 5000 RM that Alexander von Bernus, as owner of the comparable castle in Eschenau, was able to pocket for 9 months of use as a forced old people’s home. Probably it was a concession of the count towards the city of Weißenstein. In the best case, the non-Nazi Josef von Rechberg was also uncomfortable with indirectly enriching himself from the predicament of the Jewish castle residents. The town probably paid a total of 525,- RM to Rechberg’s central office, because the month of August 1942 was fully counted.

2. The contract of 26.09.1941 between the city of Weißenstein and the Jüdische Kultusvereinigung Württemberg e.V.: the city received 9, –RM per person per month from the JKVW, but at least 360 RM per month. The contract thus assumed a maximum occupancy of the rooms of 40 persons, which was to correspond to reality. On two months (November 1941 and February 1942), slightly more than 40 persons may have lived in the castle, but the monthly settlement amount never exceeded 360 RM.

In the contract, the city had undertaken to carry out some improvements and expansion of the infrastructure in the castle: Construction of a kitchen facility, a washroom, improvement of the toilet facility, improvement to the water supply line and in the electric light line. To what extent and in what quality these contractual obligations were fulfilled can no longer be traced with certainty. In total, the town of Weißenstein received a total amount of 4864.50 RM from the Jewish Community of Württemberg. October 1941 was already calculated as half a month and charged with a fictitious 41 residents.

Not unexpectedly and maliciously, the Jewish religious community also had to pay for the forced housing of its members (including the Christians among the residents, who of course were not members). So-called ‘home purchase contracts’ in which individual residents had to pay for accommodation in the castle are not known, however.

3. The contract of 12.11.1941 between the city of Weißenstein and the company Hirth Motoren G.m.b.H. Stuttgart-Zuffenhausen. In the third paragraph of the contract, Hirth Motoren G.m.b.H. undertook to take over and fulfill the tasks that the town of Weißenstein had contractually assured the Jewish Community of Wuerttemberg, namely to set up a kitchen, washroom, etc. This was not free of charge, however. This, of course, was not free of charge:

“The city of Weißenstein leaves to the company Hirth-Motoren G.m.b.H. 50% of the monthly rent received from the Jewish Religious Community Württemberg e.V. and this until the company Hirth-Motoren-G.m.b.H. is satisfied for its expenses”.

When exactly this was the case, i.e. what amount the Hirth-Motorenwerke spent on the renovation, is not known. On April 10, 1942, the town of Weißenstein transferred 992.25 RM to the Hirth Motorenwerke, exactly half of the amount it had received from the Jewish Religious Community of Württemberg until then. How the subsequent months were settled has not been handed down. Thus, it is also not clear how many Reichsmark the town of Weißenstein ultimately ‘earned’ from the forced residence.

The city of Weißenstein as well as Rechberg’s central office are ‘supporting actors’ in the evil game, also from the financial aspect. The winner is the armaments factory Hirth, which in this way gained valuable living space in Stuttgart. Background: The Hirth factories had been taken over by the Heinkel aircraft factories in June 1941 and 80 families of Heinkel armament workers were to move from Rostock to Stuttgart.

The losers were the Jewish religious community of Württemberg and, of course, the people who were forcibly quartered in the castle.

The structural situation in the castle

At first, at least two floors of the southern and partly of the eastern wing had to be provisionally prepared for the forced stay of many people, probably also with the help of local craftsmen. However, the amount of money provided by the Hirth/Heinkel company was not sufficient. The Jewish Community of Württemberg had to contribute more than half of the Hirth/Heinkel amount and was obliged to take care of the further maintenance.

This involved the provisional installation of lighting fixtures, water and sewage pipes, stoves and cooking facilities, as well as room divisions. The washroom on the first floor, which still existed at the time of the displaced persons (who were accommodated in the castle after the war), was probably installed at that time. Here several people could wash at the same time at a round basin, in the center a column with eight taps. The total living space available to the Jewish inmates was about 400 square meters; the respective use of the rooms can no longer be traced with certainty.

Only one toilet, located on the second floor, was available to the inmates, who numbered over 40 at times – other temporary toilets outside the building are possible. The primitive heating system consisted of old tile stoves and individual ovens. After the structural preparations, which were intentionally inadequate, the furniture transports from Stuttgart began, probably by train and then by trucks, furniture vans or peasant carts to the castle.

Life in a forced community

Probably until November 1, 1941, 42 Stuttgart residents were assigned mainly to the south and (partly) the east wing of the castle. Officially, the mostly displaced from “Jewish houses” were only allowed to bring one table, one chair, one bed and one wardrobe per person. However, according to what Weißenstein citizens were able to purchase at auction after the dissolution of the forced dormitory in August 1942, the arrangement was not strictly enforced. There were also carpets and decorative cabinets among them, in short ‘nice things’ with which the new inmates associated ‘home’.

A vague insight into the room and living situation at the beginning of the forced dormitory is given in the letter written by Sofie Kroner on November 14, 1941 to her daughter who had escaped to the USA:

“The dormitory – we are together there and also the dining room are very pleasantly heated. Above me lies Miss Levi, who always went with the Gutmann, dear Nelly. I have already furnished my little corner quite nicely, as the manageress Mrs. Falk – formerly of the laundry in Stuttgart – praised me very much. Several inmates already emphasize that I am a brave, good and modest woman – what more can one ask! Otherwise, there are lively disagreements among ‘people among themselves’, we are over 40 people in total. I keep neutral because I love peace.”

Mrs. Kroner visibly makes an effort to gloss over her living situation to the worried daughter. It nevertheless becomes clear that there was hardly any ‘privacy’ in the castle and that the living situation was conflictual. The living situation appears much more relaxed in the protocol of October 6, 1948, when the tax official Paul Mayer was questioned:

“The Jews, all of them elderly persons, the number is not known to me, lived in the castle in one wing on three floors. In the individual rooms occupied by the Jews, they had placed their private furniture, which they had brought with them from their earlier apartments in Stuttgart. They themselves slept in their own beds, and I had the impression that the Jews at that time were still very well provided with trousseaus and the like, although in part there were many older things.”

There are indications that Mayer, however, describes a different time period of the forced dormitory than Mrs. Kroner. Namely, he mentions ‘Heilig’ as the name of the mayor, who did not take office until March 1942. If Mayer’s recollections refer to the time before the last deportation in August 1942, then only 27 people lived in the castle and more privacy would have been possible in the remaining space.

Many of the inmates may have already known each other from Stuttgart, where most had lived in assigned apartments. In two Stuttgart ‘Jewish houses’ alone, a total of 13 people lived who later met again in Weißenstein: eight in Rosenbergstr. 105, five in Wielandstr. 17. Apart from friends and acquaintances, people who were closely related also lived in the castle. The only family was the Jewish caretaker couple Johanna and Isak Falk with their daughter Carry. Sibling couples were: Julius Stern and Anna Einstein, née Stern, Marianne and Suse Weil and Ida and Elsa Wormser.

Mothers and daughters: Sofie Rosenthal and Johanna Harburger, née Rosenthal, Kornelia Mayer and Lucie Mayer, possibly also Babette Leiter and Bella Weil, née Leiter. Hermann Wolf and Frime Rosenrauch were related: their son Heinrich Rosenrauch was married to Hermann Wolf’s daughter Alice. (The younger generation, however, did not live in the castle).

Even though a total of 60 people inhabited the forced dormitory during its existence, only 43 of them could have met there. The reason for this is that 17 of the 42 people who (demonstrably) lived in the castle from November 1941 on were already deported to Riga / Jungfernhof concentration camp on December 1, 1941. 15 other Stuttgart residents did not arrive at the Schloss until the beginning of February 1942.

It is not possible to determine exactly when the two persons who were not from Stuttgart arrived. Only 16 persons remained here for 10 months from the beginning until the dissolution of the institution at the end of August 1942. It has been handed down from other forced residential homes that the residents were allowed to receive visitors. At least one visit is also documented for Schloss Weißenstein: Heinrich Rosenrauch met here with his mother Frime about 6 weeks before her deportation.

Women, men, old, young, housewives and artists

The cramped living space in the castle was shared by 48 women and 12 men. The youngest of all was Carry Falk, born in 1925; at the other end of the age spectrum was Sofie Rosenthal, born in 1855. While the average age was 56, which kept us from talking about a ‘retirement home’, the 70 to 79 – year olds made up the numerically strongest birth decade with 24 people, followed by the 60 to 69 – year olds with 15 people. 31 persons had already lost their spouse, 19 persons were single, 6 divorced and only 4 married. In terms of social affiliation, the upper middle class dominated, often merchant families, including many self-employed. The social spectrum ranged from members of the upper middle class, such as Johanna Kaulla or Rosa Lindauer, to the less privileged, such as the domestic servant Mathilde Gärtner.

The only academic was the retired physician Dr. med. Max Hommel. Among the women, those who worked in creative professions stand out: The painters Elisabeth Kaltenbach and Käthe Löwenthal, the writer Ida Wormser, who published under the pseudonym ‘Linden’, and the self-employed photographer Erna Bellson. How did the inmates spend their time in the castle?

Boredom probably prevailed and the fear for their own lives, at the same time for those of friends and relatives. Probably as many letters as possible were written – the only chance for contact with the ‘outside world’. Unfortunately, so far we have only the letter quoted above. Those who could sew and knit must have had a lot to do, if there was not a lack of material: Already since January 1940, the ‘Reich clothing cards’ for Jews had been canceled. New clothing could no longer be purchased; the existing clothing had to be preserved as best as possible.

General Administration

Isak Falk (54), known as the “administrator” and “janitor”, was responsible for all matters concerning the inmates of the home throughout the entire period. His wife Johanna (45) and his daughter Carry (17) assisted him as caretakers and kitchen staff. The Falk couple had run a laundry in Stuttgart from 1932 to 1939, after which they worked in the administration of the Jewish old people’s home in Sontheim near Heilbronn until its forced closure. Johanna Falk is referred to by Sofie Kroner in the letter excerpt reproduced above as ‘Leiterin’. This indicates that the Falk couple considered their main areas of work (office work and field work) to be of equal importance. Their daughter Carry, who had attended the Jewish boarding school (originally an orphanage) ‘Wilhelmspflege’ in Esslingen from 1939, will have received housekeeping training there – pragmatic preparation for a hoped-for life in emigration.

The Falk family was thus one of the few Jewish Germans who in 1941 / 42 were allowed to engage in occupational work that could not be described as forced labor. Admittedly, their living conditions ultimately differed little from those of the ‘normal’ inmates, whose fate they also shared.

The 34-year-old Berta Bona Rosenfeld may also have belonged to the ‘staff’ during the first two and a half months. However, on January 17, 1942, she had to transfer to the forced residential home Schloss Eschenau near Heilbronn as an assistant and from there to the forced retirement home Schloss Dellmensingen at the end of April.

Only Mr. and Mrs. Falk were allowed to go to surrounding towns for supply purposes. Mayor Wahl had arranged for the laundry of the Schoss inmates to be washed primarily in the communal washing facility of the savings and loan association in Nenningen (the neighboring village of Weißenstein).

This task will probably have been organized and also partly taken over by the expert Johanna Falk. In comparison with the forced old people’s home at Dellmensingen Castle, it is noticeable that in Weißenstein there were few care personnel on hand: it was different in Dellmensingen: There, at least 16 persons, among them professionally qualified, looked after the 128 inmates. Were the (on average younger) inmates of Weißenstein Castle more able to care for themselves?

An exception: The hairdresser comes to the castle

As of May 29, 1942, it was valid in Nazi – Germany: Jews are forbidden to visit barbershops. A decision that was to contribute to the humiliation and further exclusion of the Jewish population. However, the inmates of the castle could enjoy regularly groomed hair. The reason for this can be found in the affidavit of the master hairdresser Franz Biegert, Böhmenkirch, a member of the NSDAP:

“In the fall of 1941, the head of the local group and mayor August Wahl instructed me to serve the Jews housed in Weißenstein Castle, which I accepted and served them (men and women) every Monday. In January or February 1942, A. Wahl and I were reported to the district leadership and threatened with expulsion from the party, but I nevertheless continued to serve the Jews at the request of the local group leader and mayor.”

Cold

Keeping the high rooms in the castle warm, as Mrs. Kroner still praised, became a problem in the course of the winter from 1941 to 1942. A very severe, snowy winter set in with December and lasted until February 1942. The average temperature was – 4°, on some days the thermometer dropped to minus 15°.

The quota of heating material granted by the SS to the castle inmates was not enough, because it was still exceptionally cold until the beginning of April. The then mayor and NSDAP local group leader August Wahl, an enthusiastic member of the Nazi party since 1930, had nevertheless intervened on behalf of the Jews in the castle and procured 150 hundredweight of coal and additional firewood.

As of January 10, 1942, Jewish Germans were required by Nazi decree to hand over all wool and fur items; how strictly this was handled in Weißenstein is not clear from the files. When it became clear that the people in the castle were suffering from cold, blankets were secretly brought to the castle by the inn ‘Schenke’ and friends of the landlord family Nagel.

Enough to eat?

With the beginning of World War II due to the invasion of Poland (early September 1939), food was generally only allowed to be distributed upon presentation of food stamps. Those for the Jewish Germans were marked with a red “J”. The quantities of basic foodstuffs available to them were, however, significantly lower than for non-Jewish citizens. The castle inmates must have already known hunger from Stuttgart, especially since they were forced to shop in Stuttgart’s only ‘Judenladen’ from April 1941, which was only inadequately supplied with food.

In addition, from April 6, 1942, the weekly ration of bread and meat for the reference cards was reduced throughout Germany. This will also have affected the already reduced food rations of the Jews. Hunger presumably became a constant companion in the castle as well, even though the most drastic restrictions (no meat, no milk, no eggs) for ‘Jews’ were not enacted until September 1942, when the forced residence had already been dissolved. Until then, meat was probably supplied at least within the narrow limits of the ‘J’ food cards.

Mayor Wahl had instructed the shopkeepers to supply the Jews “on a regular rotational basis.” It is known that the butchers Julius Schielein and Bernhard Kuhn (Sonnenwirt) supplied the home residents with meat (beef as a rule), although the animals were not killed by slaughtering, as required by Jewish religious laws. The administrator Isak Falk was able to obtain further food on reference cards from the Weißenstein stores.

On the subject of food supplies, the Spruchkammer file of 26.1.1948 on Mayor August Wahl also provides information. Regarding his exoneration it states:

“In a market garden he continuously procured fruit and vegetables and, when the market gardener initially refused, made the delivery possible after all by having the invoices written in his name. Because of this behavior he was reprimanded by the district leadership. The person concerned links his sudden enlistment in the Wehrmacht to this behavior of his.” The nursery was the horticultural business of Walter Bleich in Donzdorf. The latter declared in lieu of oath on December 15, 1946:

“When the Jewish residential home in Weißenstein was established in 1941, Mr. Wahl, who was mayor of Weißenstein at the time, personally entrusted me, the master gardener Walter Bleich in Donzdorf, with the supply of vegetables for this residential home. He completely agreed with me that I carried out these supplies abundantly and sufficiently. With his knowledge and agreement – the invoices and receipts all passed through his hand – the kitchen was sufficiently supplied with vegetables and salads, apples and lemons and spices throughout the winter until the dissolution of this dormitory in the summer of 1942. For him as the mayor in charge, this course of action meant a great risk, because the National Socialist state had no understanding for it at all.”

Mayor Wahl had also rented a brewery cellar in order to be able to store the quantity of potatoes he had secretly bought privately for the castle residents. As an ‘Aryan’ and NSDAP member in a political office, Mr. Wahl was allowed to get away with a lot: even being ‘nice to the Jews’ – in the end also just an indication of the arbitrariness to which Jewish Germans were exposed.

In the first months of the forced residence, the operators of the inn ‘Schenke’ had courageously taken care of the food supply of the castle inmates: Hedi Nagel, the still underage daughter of the innkeeper’s family, (described by a local Nazi in a letter as a ‘champion of political Catholicism’), secretly brought food from the inn’s kitchen to the castle. Also, locals are said to have deposited milk in containers in a hidden place behind the castle.

All the recollections and statements about sufficient food supply come from local eyewitnesses or from those politically responsible such as Mayor Wahl and his ‘exoneration witnesses’. However, many questions remain unanswered, which could have been answered only by the former castle – inmates. There are indications that hunger remained a constant threat for them.

For example, those inmates who were still able to walk and who ran the risk of being denounced for leaving the castle tried to exchange valuables for food. Among them was Mrs. Chana Eugenie Grünwald (66), when she, presumably without wearing the discriminating ‘Jewish star’, went to the village of Treffelhausen, about 1.5 km away from the castle. According to the interrogation testimony of Oberwachtmeister der Reserve Moll of the Weißenstein police station, such attempts to exchange additional food had been “generally known”, which means that they had already occurred several times. It was probably tolerated a few times, but not in this case: Mrs. Grünwald was denounced on the occasion of her clandestine excursion, arrested and sent to Ravensbrück concentration camp as a ‘political’ prisoner on August 14, 1942. Her life ended on October 7, 1942 in the extermination camp Auschwitz.

Another indication of the inadequate supply situation: The diagnosis “scurvy” (deficiency disease due to lack of vitamin C) was registered at the time of Therese Fried’s death. She was the only person to die directly at the castle.

Medical care

While the Stuttgart Jewish physician Dr. Viktor Steiner was able to care for the health of the inmates in the forced old people’s home at Dellmensingen Castle (and other institutions), those in Weißenstein were left without medical care. The physician responsible for the Weißenstein castle, Dr. Josef Mangold from Donzdorf, was only allowed or required to make control visits to the castle from time to time to determine whether there was a parasite infestation or epidemic outbreak. (The fact that local lore spoke of ‘venereal diseases’ indicates anti-Semitic prejudice). Whether Dr. Mangold provided medical care without ‘commission’ is not known. Dental care has not been handed down.

Admittedly, there was also a physician among the Weißenstein inmates: Dr. med. Max Hommel, retired general practitioner. Unlike Dr. Steiner, however, he had no mandate to practice and thus no access to medicines and medical equipment. Presumably, however, his advice helped sufferers in ‘minor cases’. He apparently could not sufficiently help the castle resident Friedrich Siegel (67). In his distress, Mr. Siegel did not adhere to the exit restrictions and went to see a doctor in the village of Böhmenkirch, about 4-5 km away. Afterwards, Mr. Siegel stopped at a tavern there, where he is said to have made ‘pacifist remarks’. A visitor to the pub must have denounced him, and the local police officer arrested Mr. Siegel. He was briefly interrogated, but then released for the march back to Weißenstein. A week later, a Donzdorf gendarme arrested him in the castle. On August 21, 1942, he was sent to the Dachau concentration camp. There he died on October 11, 1942, officially of “failure of heart and circulation due to intestinal catarrh” in the prisoner infirmary.

In the castle directly, however, as mentioned above, Therese Fried, née Falk died of scurvy on March 20, 1942. Her death not only raises questions about the nutritional situation, it also indicts the inadequate medical care of the castle inmates. Today, her grave can be found in Göppingen’s main cemetery, Israelite section. However, it is possible that Mrs. Fried’s body was first buried in Weißenstein and only later moved to Goeppingen.

While 14 of the 128 inmates died in the forced old people’s home at Dellmensingen Castle, there was only one death in Weißenstein. Whether this discrepancy can be explained by the different average age (in Dellmensingen the people were on average 12 years older) or whether the care situation in Weißenstein was comparatively better must remain open. In any case, the better medical care in Dellmensingen did not guarantee greater chances of survival.

On Faith

According to the racist delusion criteria of the Nazis, from 1938 on also Christians were considered ‘Jews’ if they had Jewish-believing parents and grandparents. (They were all given the additional first name Israel or Sarah in their identity cards). For this reason, there were also several Protestant Christian women among the inmates of the forced home. Known so far are: Elisabeth Kaltenbach, Johanna Kaulla, Käthe Löwenthal, Meta Oppenheimer and Elisabeth Stein. That other inmates defined themselves as non-religious is possible.

The vast majority adhered to the Jewish faith, but pastoral care by a rabbi was not possible. In order to hold a Jewish service, religious laws require the ‘minyan,’ a quorum of ten or more Jews of religious age. This requirement was met (mathematically) in the forced residence only for a short time, namely between the beginning and the end of November 1941. After that, there were no longer 10 Jewish men living in the castle at any time. Since Sophie Kroner was the widow of a rabbi, it is conceivable that she was sought out as a contact person for questions of faith. Perhaps she also led a prayer group. On the first floor, in the middle of the living quarters of the castle’s residents, was the castle chapel, which, however, was not available for use.

In a parish report written down after the war, the local Catholic priest Josef Mühleisen reported that he had secretly received a Catholic woman of Jewish origin for confession and communion in his church shortly before her deportation from the castle. Unfortunately, his statements about the person: “Catholic concert singer from Mainz” could not be assigned to any of the inmates so far.

Contact with the local population

The space for movement for the inmates of the castle was very limited. Officially, only the inner courtyard of the castle, with the exception of the Altane, as well as the access road on the north wing up to the bridge, and the path behind the castle along the hillside were permitted for going out (one cannot speak of walking). Thus, the citizens of Weißenstein could hardly see anything of the inmates from the village. They lived in a ghetto even without fencing. In the Ludwigsburg Spruchkammer files ‘In Sachen August Wahl’ of January 26, 1948, the mayor of the time is credited:

“He also gave the evacuees greater freedom of movement on his own responsibility.”

More specifics are unfortunately missing.

Even though the inmates were generally not allowed to leave the castle grounds, there were a few places outside that they were allowed to go to. They could settle their financial affairs, for example, at the branch of the Württembergische Landessparkasse. This was run by Emma Wamsler (house on Hauptstraße opposite the post office) during the opening hours of her grocery store. In general, the Wamsler family’s store seems to have been where most of the contacts were made. The caretaker, Mr. Falk probably needed a helper to carry the purchased goods for his regular shopping. The thought is obvious that he thus alternately enabled one or the other to leave the castle once ‘legally’. Most likely this is how the friendly contact between Julius Stern and the Wamsler family came about. The multiple visits of Julius Stern to the Wamsler family (later photo Wamsler couple) are a sign of courage (on both sides) and represent the exception to the rule.

In the memory of contemporary witnesses, there is also talk of two approximately 15-year-old and two approximately five to seven-year-old ‘Jewish’ girls who lived at the castle and also attended the Weißenstein school. Since the list of Jewish inmates of the castle has now been clearly established and, apart from Carry Falk, no young people were among them, it is unlikely that those remembered were ‘fully Jewish’ children whose parents lived in the forced residence. Even more so if the memory of school attendance is true: Jewish children had to leave the public (elementary) schools already after the pogrom night in 1938.

Deported, murdered and robbed

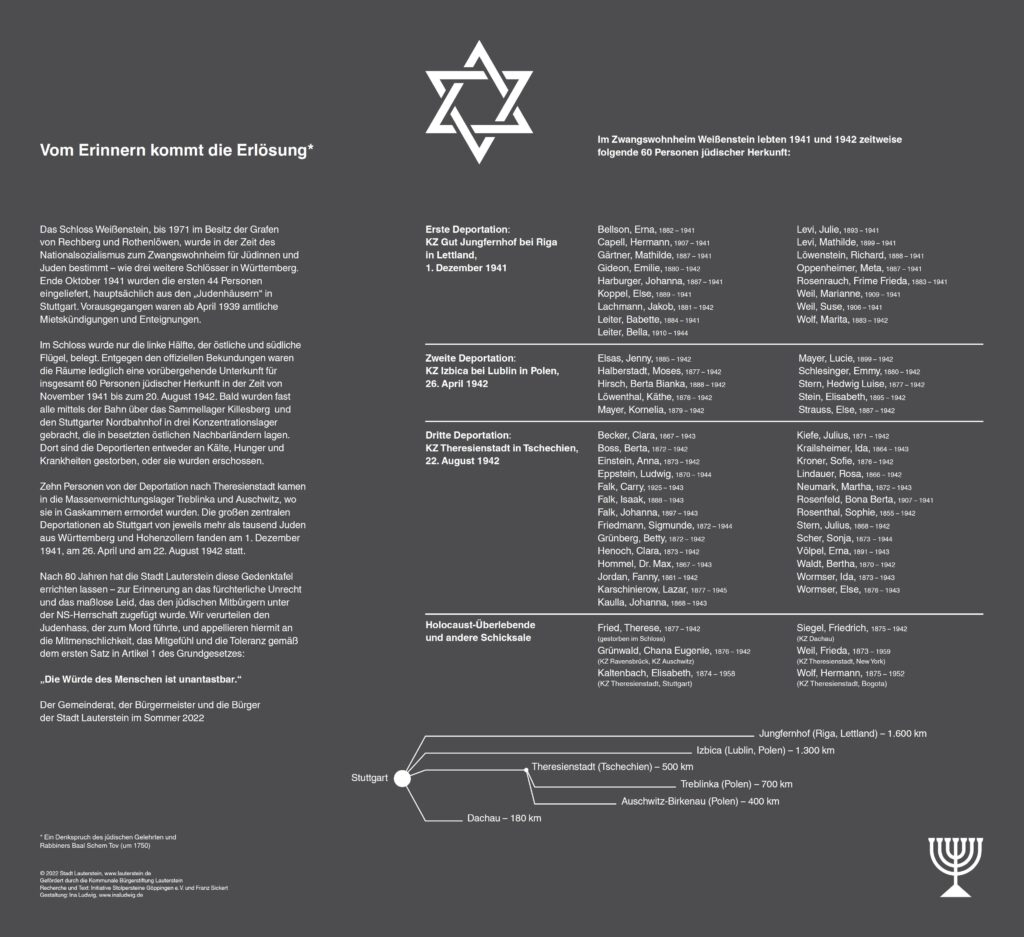

The stay in Weißenstein Castle was for all inmates an oppressive waiting for deportation and murder. The memorial plaque on the Weißenstein church square provides information about who was deported, when and where. Only three of the 60 people who were housed in the castle survived the Shoah.

The last hours of the castle inmates in Weißenstein are documented by later interrogation protocols, at least for the first deportation at the end of November 1941. (Detailed in Karl-Heinz Rueß, Die Deportation der Göppinger Juden, p. 29ff.) There were few officials who were actively involved in the first step of each of the three deportations, i.e. the expulsion from the castle: the policemen Michael Frank from the Donzdorf police station and his Weißenstein colleague Andreas Moll. They did ‘duty according to regulations’, searched the luggage of the Jews for ‘illicit items’ and carried out a body search on the men. For the women, this was to be done by the Weißenstein midwife Maria Hänle.

K. – H. Rueß (see above p.32) writes about this: “When she arrived at the castle at 4:30 in the morning, the reason for the summons was only revealed to her on the spot and the expected task was explained. Marie Hänle refused to be strip-searched in the presence of men. Finally, she was told that a pat-down of her clothing would suffice. When she realized that little value was attached to the examination, she abandoned her task after having patted down several women. She was not called to the castle during the later deportations.”

The policemen accompanied the outcasts to the train station and rode with them on the train to Stuttgart to ‘hand them and their last cash over’ to the Gestapo. It is believable that none of the policemen behaved in an unfriendly or even cruel manner. Both men ‘functioned’ unobtrusively as cogs in the machine of robbery and murder set in motion by the Nazi Germans. Among the men still mentioned were Chief Inspector Niess of the Geislingen tax office and his colleague, retired enforcement officer Paul Mayer. Both ‘administered’ the robbery of the Jews. Still completely caught up in the language of the Nazi era, Paul Mayer stated in 1948:

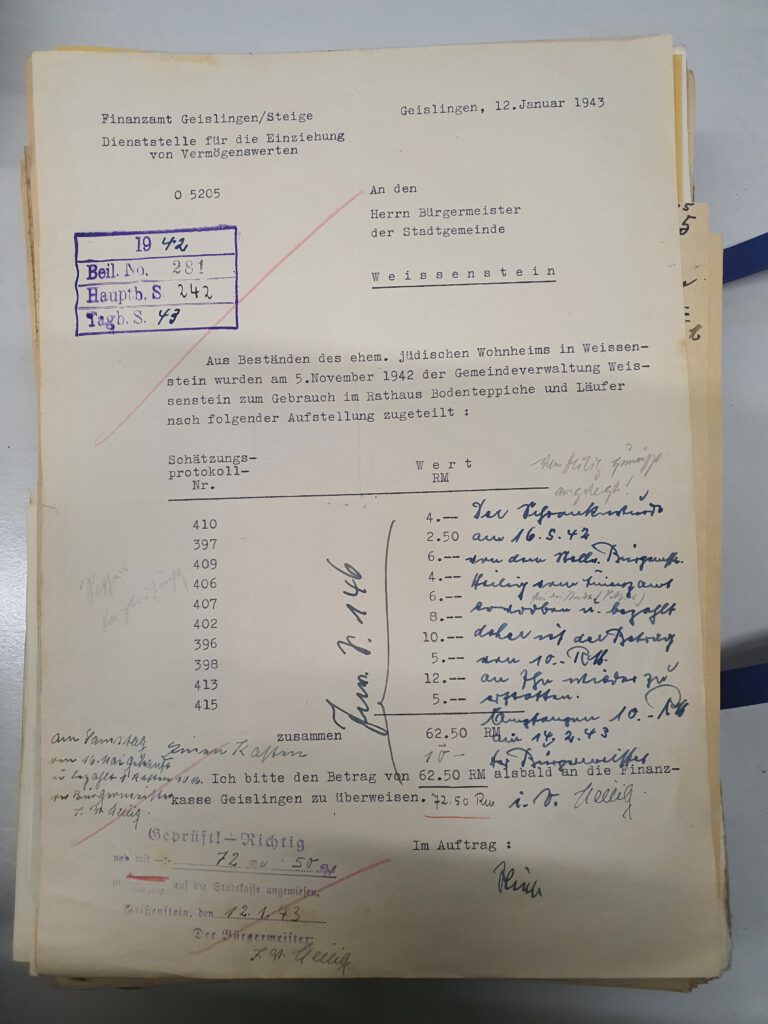

“Already at the time of the first removal of the Jews, we recorded the Jewish property and evaluated the individual items such as furniture, trousseaus and other items with Mr. Rösch, the municipal auctioneer of Geislingen. At that time, after the departure of the first Jews, there was an auction at which I myself was present with Mr. Niess and Mr. Rösch. The auction took place in the castle. The proceeds of the auctioned items were kept in a file by Mr. Rösch and the cash proceeds were settled with the tax office. The cleaning ladies (from Weißenstein) received some old items from the Jewish estate from Mr. Niess for their work. I myself, as well as Mr. Niess, took nothing away from the things.”

Apart from the German state, some Weißenstein families also profited from these auctions.

As an invoice testifies, the town of Weißenstein also bought a few carpets that had belonged to the former castle inmates.

Memory on the spot

Family memories of the forced dormitory and its inmates existed and still exist in Weißenstein. But in the decades after its dissolution, no one made it their business to collect them and document them in a local historical framework.

It was not until 1988, in the appendix to the new edition of Dr. Aron Tänzer’s book ‘Jews in Jebenhausen and Göppingen’ that the then Göppingen town archivist Dr. Karl-Heinz Rueß published a preliminary list of names and life data of Weißenstein castle inmates.

Mr. Rueß deepened his research and in 2001 was able to contribute a five-page text to the brochure ‘Die Deportation der Göppinger Juden’, which he wrote. Initially independently of each other, Franz Sickert, a native of Weißenstein, living in Mutlangen, and Klaus Maier-Rubner of the Initiative Stolpersteine Goeppingen began since about 2018 to deal with the subject of forced residence Schloss Weißenstein.

Franz Sickert benefited from the fact that he could fall back on contacts in the village. Based on the publications of Dr. Rueß, the research was continued together. Since most of the Schloss Weißenstein inmates had previously lived in Stuttgart, it was possible to obtain information in many cases from the biographical texts written by members of the Stuttgart Stolperstein initiatives.

Helpful in the overall context of the forced dormitories were also the qualified publications on the similar institutions in Dellmensingen, Eschenau and Herrlingen. In 2021, there was a close exchange with the city administration of Lauterstein, where Weißenstein is now a sub-municipality, especially with Mayor Lenz. The idea arose to commemorate the inmates of the forced dormitory with a memorial plaque.

Ina Ludwig at the unveiling of the commemorative plaque

On September 18, 2022, this plaque, designed by the graphic artist Ina Ludwig (Stuttgart), who comes from Weißenstein, was unveiled on the church square (Im Städtle 33). Since the end of October 2021 (after exactly 80 years), the history of the home and its inmates was published by Franz Sickert in twelve episodes in the Lauterstein newsletter.

In 2022, interested parties were given intensive insights into this oppressive period of local history at an ecumenical service in the Weißenstein church and at a public information event held by the community in the TV hall. In the castle itself, the current owners, the Kage family, commemorate the history of the building during the Nazi era with an information board. In the future, the still missing biographies of castle inmates will be researched and published here.

(24.04.2023 Klaus Maier-Rubner and Franz Sickert)

Leave a Reply