Hauptstr. 11

Love Match with a Foreigner

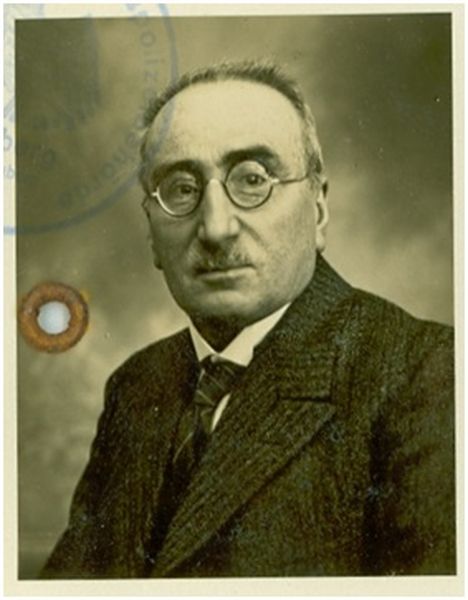

Irma May from Camberg married Julius Fleischer from Göppingen in November 1919, a true love marriage, which was unusual on the middle class of that time. Irma’s father Moritz May was the owner of a metal goods wholesaler and very successful. In Irma’s family – she was the only child of Hedwig and Moritz May – Jewish culture was cultivated, which did not exclude good living and art. Later in Göppingen Irma Fleischer also cultivated her cultural heritage: she went to the Stuttgart opera frequently and was interested and well informed about fashion.

Her daughter Doris-Sylvia remembered that her mother was seen as somewhat extravagant in conventional Göppingen, as well as in her husband’s family: “The ladies of father’s family bought their clothes to last – the cloth was certainly the best quality – while mother had new clothes every season.” Her daughter’s fashionable appearance was also important to her: “I knew that my skirts were shorter than those of my schoolmates – mother had said they were dressed like peasants – but children like to conform.“

Between 1920 and 1927 the children Arnold, Doris-Sylvia, Susanne and Richard were born. As is common in the upper middle-class of this time, the children were cared for and brought up by a governess. Hedwig (“Hede”) Herbster from Gosbach was especially fondly remembered by the Fleischer children. Hede stayed in contact with the family even after she stopped working for them and she later even openly contradicted the Nazis. She made a public announcement that she had gotten to know Jews as decent and honorable people. It wasn’t until she was threatened with a concentration camp that she fall silent.

Julius´ Vocation

At the time of their marriage, Julius Fleischer was regarded as a “good catch” because he and his younger brother Arthur were the intended successors in the management of their father’s corset factory – a position which he did assume after the death of his father, Samuel Fleischer. Julius got an education at famous Reutlingen ‘Technikum’ in 1900 7 01. If it hadn’t been for his familial responsibilities, Julius Fleischer would have studied medicine and the art of healing in a wide sense was to remain a decisive factor in his life. Over the years he withdrew more and more from the management and followed his calling. While not as a doctor he did practice as a healthcare practitioner, healer and inventor of natural medicines. In his own laboratory he created elixirs; one of these with the name “Olvicor“ is remembered by contemporaries. For many years Julius Fleischer was an active member of the Göppingen Kneipp Society, among other things as the treasurer. Especially people from the surrounding small towns valued Mr. Fleischer’s advice and help which meant he was often on the road on his bycicle. His wife did not always talk in favour of her husband’s new “occupation”. Later their daughter Doris (Sylvia Hurst) writes: “Twenty years ago mother had married a manufacturer of corsets, he was now a doctor of naturopathy, a mystic.” Mrs. Margret Duisberg, a friend of the Fleischer family, writes: “Julius Fleischer was held in high regard by the people here– outwardly modest, he was considered very knowledgeable and helpful and you always felt like he knew a lot!”

Friends with Albert Einstein

Julius Fleischer’s circle of friends extended far beyond Göppingen. His children Doris and Richard remembered that the doctor and author Friedrich Wolf visited their father; he was also a supporter of alternative medicine. The most famous visitor and friend of Julius Fleischer was certainly Albert Einstein, who was actually a (very) distant relative and was called “uncle” by the children. Sylvia Hurst writes about this: “As a child, he [A.E.] and his sister Maja spent many of their school holidays with our family as the children (of both the Einstein and the Fleischer family, – kmr) were of the same age. My father and he became lifelong friends. Father very seriously believed his extraordinary gift of medical clairvoyance was God given; his one-ness with nature was a part of it. The latter he shared with Albert, both claiming they could feel the forces of the universe and the cosmos.” Besides the intellectual similarities, the quality of Irma’s noodles, “Spätzle”, were supposedly also one of the reasons for Einsteins’ visits. Then again the Fleischer children also looked forward to the generous presents from “Uncle Albert”. Besides these prominent Jewish friends, Julius Fleischer’s circle of friends was made up mostly of non-Jews.

A Surreal Nightmare

Julius Fleischer was initially unconcerned about the strengthening of the Nazi movement. Sylvia Hurst writes: “The Jewish population in my town was divided into two groups: the ones who believed in emigration as an immediate and urgent measure, and the group, to which my parents belonged – or I should say my father – maintained that Nazism was a crazy and unreal dream, and that the bad times must pass. However, just to be on the safe side, Father went to the American Consulate in Stuttgart to obtain a Waiting Number.”

The transfer of power to the Nazis marked the rapid ostracism and disenfranchisement of Jewish citizens. Julius Fleischer was forced to step down as president of the Kneipp Society. Former acquaintances, including many artists who had utilized Fleischer’s hospitality for weeks at a time, avoided their former benefactor. Neighbours on Hauptstr. hung up signs on the doors to their stores which say “Jews not welcome here”. Of their own initiative, as Richard Fleischer remembered, the neighbours delivered daily telephone reports about “the Jews” to the police.

The family’s financial situation got worse and worse. Sylvia Hurst wrote about the year 1937: “Father’s income was nil; he considered it wrong to charge for his gifts, and he mostly supplied his ‘patients’ with the medicaments free.”

To the police station

During the Pogrom Night on November 9th, 1938 Irma Fleischer was visiting her parents, who lived in Frankfurt am Main. Daughter Doris and son Richard were not at the logdging in Hauptstraße in Göppingen too. Silvia Hurst, née Fleischer, writes in her book “Laugh or Cry” about the based memories on her siblings Arnold and Susanne: “It was in the early hours of the morning when two SA men demanded entrance to look for Julius Fleischer. He managed to yell to his children Susanne and Arnold, “I’m just going to the police station with these gentlemen. For inquiries. I’ll be back soon. You’d better go back to bed, both of you. If I am not home by breakfast, ring your mother. Not to worry.” Julius Fleischer got to be imprisoned and humiliated in Dachau concentration camp for the time of a whole month.

Mrs. Hurst writes on: “I received a cheerful letter from him, saying he was in good health. He wrote that his breathing exercises had kept him quite fit during his stay at the camp.” When she later saw her father, it became clear that these words had been written to calm her. “I had a shock when I saw my parents again. Father looked so thin and the crew cut was terrible. I remarked on it; Mother smiled, ‘It’s much better now. You should have seen him when he came out of the camp. He was shaven close then.’ Mother looked fragile; I noticed a white streak in her hair.”

Son Richard had traumatic experiences as well. The boarding school “Wilhelmspflege” in Esslingen where he stayed was raided in the Pogrom Night. All the equipment was demolished and the teachers were tortured. Richard remembered in a letter to Peter Conrad on 26th of November 2009: “The noise. The cries. The teachers tried to protect the helpless children of the mob. Not the slightest chance.”

Robbery – the elder children take flight

At the beginning of the year 1939 Jews were forced to give all of their valuables to the German government. The family was already impoverished and now also lost personal mementoes such as a valuable pearl necklace which Julius had given to his wife as a wedding present. A ridiculous 13 Marks are credited for this piece of jewellery. “The Nazi official must have suffered from writer’s cramp” was Julius Fleischer’s comment on the robbery.

The couple’s plans to emigrate to England fall through because a relative living there did not see herself in a position to act as a guarantor for them. As a matter of fact, she had already acted as a guarantor for several other closer relatives. At least it was possible for their older son Arnold to flee to London in April 1939 by accompanying an older relative. In July his sisters Doris and Susanne followed him as part of the Refugee Children Movement.

During the war Arnold Fleischer was deported from England to Kanada as a “hostile foreigner”. There he worked in a lumberjack camp. After the war he received Canadian citizenship, married and got to be a successful corporate and tax consultant. He died in the age of 48 in 1968 without any children of his own.

Susanne Fleischer emigrated to the US, got married the Doctor Philip Nassau and had a daughter and a son. She died 1975 after a car accident.

Doris-Sylvia Fleischer (married name Sylvia Hurst) stayed in England, worked in various creative occupations, e.g. as fashion designer, and gave birth to a daughter.

During their time in England, the Fleischer children had almost no opportunity to find out anything about their parents and their youngest brother. Their parents had decided not to send Richard, born in 1927, alone to a foreign country – an understandable decision with terrible consequences.

Richard recalled from his time in Göppingen that the remaining family had to share their remaining apartment at Hauptstraße 11 with the Sally Frank family: “The Franks lived with us in a one-room apartment. They had a big white-haired dog called ‘Roland’. I was very lucky to see them alive again in Pirmasens in 1945.”

Other Jewish people were also temporarily assigned to the Fleischer family’s apartment: Wilhelm Fleissig lived at this address from May 1940 to May 1941 and the Eislingen family Lerner was registered here for one month in 1939. It is uncertain whether the Fleischer family were able to remain in their original home until their deportation. They were probably driven out of their home altogether and were housed in the ‘Jews’ house’ at Mörikestrasse 30, where Jewish families or individuals had been forcibly evicted.

There are letters preserved from Hedwig Frankfurter, Sara Zitter and Isidor Fränkl dated between the years 1939 – 1941. The three of them were of different regional and social heritage. Most probably they were not in close contact with one another before the time of the Nazi regime.

Since times of affliction the name of Julius Fleischer is mentioned by all of them. Because of this letters it can be assumed that Julius Fleischer fostered the contact between the family members left, after many other jewish family had shunned.

He ensured the contact within the remaining jewish community members, as rabbi Wallach out of Laupheim most probably was not that familiar with all of them, moreover he stayed in Göppingen only until August 1939.

Destination: Riga / Camp “Jungfernhof”

On November 28, 1941, after one night in the Schiller School gym, Irma, Julius and Richard Fleischer were “accompanied” by officials of the Göppingen police to the train station. Richard wrote about the first stop at the camp on Killesberg in Stuttgart: “Yes, I remember Killesberg. The sickening smell, the disconcertment. Sleeping on the floor. The queueing up for the toilet. But the worst how the Gestapo treated dad, witnessed by me as terrified little boy.” (Letter to Peter Conrad on 29th of September 2009)

The way on the family was deported to Riga to camp Jungfernhof, a previous agricultural estate. There Julius Fleischer died a miserable death on February 26, 1942 as result of frostbite. Exactly one month later Irma Fleischer was murdered, probably shot to death or asphyxiated to death in a wagon purposely prepared for. Richard Fleischer, 14 when he enters the deportation camp, survived the torture of several work camps. He recorded his sufferings in a letter in 1945. (See end of this article)

The mother of Irma, Hedwig May, was deported in September 1942 from her makeshift in Frankfurt to the ghetto Theresienstadt. May 1944 she was murdered in Auschwitz.

In May 2014 two Stolpersteine were laid in Bad Camberg, where the parents of Irma Fleischer, Hedwig and Moritz May, originally domiciled.

The historian Martina Hartmann-Menz documented the fate of the couple thoroughly:

http://www.bad-camberg.info/cms/index.php/wissenswertes/stolpersteine/steine/2384-hedwig-may

http://www.bad-camberg.info/cms/index.php/wissenswertes/stolpersteine/steine/2383-moritz-may

The brothers of Julius, Bernhard and Arthur Fleischer, the cousins Rosa Fleischer and Emilie Goldstein were murdered, the cousin Pauline Guggenheim assisted suicide.

We were able to obtain a lot of the information about the Fleischer family from Sylvia Hurst’s book “Laugh or Cry” and we would like to thank late Richard Fleischer for his willingness to answer our questions. After the war he emigrated to the United States, where he met his spouse June. He was successful in his own business as a tiler. He retired on an idyllic location near a lake in Canada. In July 2010, a few weeks after visiting Göppingen, he unfortunately died on cancer.

Sylvia Hurst died in July 2016, the same year her old friend Margret Duisberg, who as well shared memories with us, passed away. Not being of jewish origin Margret Duisberg never departed out of Göppingen.

We are also thankful to Peter Conrad, the local historian out of Rodalben / Paladine, who disclosed the letters he received from Richard Fleischer. Thank you too to Martina Hartmann-Menz out of Elz, who helped us by sharing information and photos about the parents of Irma Fleischer.

On May 1, 2010 Gunter Demnig laid the Stumbling Stones for Irma and Julius Fleischer in front of the house at Hauptstraße 11. Richard Fleischer, Sylvia Hurst and some more family members were present. Students from Freihof-Gymnasium also provided information about the murder victims and assumed the sponsorship for the stones.

30.08.2025 (kmr/ir/wb)

Letter from Richard Fleischer written in 1945

This letter was given to us by Richard Fleischer’s cousin Erwin Fleischer on the occasion of the visit of expelled Jews in Göppingen at “Maientag” in 1984.

Below is a typed version of the letter.

Dear Eva,

Today, November 7, was the happiest day. It has been weeks since I have felt as happy as today when Aunt Bernhard gave me the letter. I was very, very appy to finally hear from you, dear Eva, that my siblings are doing well. It is very sad that your dear father and mother are no longer alive to enjoy the happy times that are coming. I remember in our concentration camp we also knew that Dutch and French Jews arrived near Lublin in the spring. The name of the camp was Izbica. Most of the transports that arrived were already gassed in the trains. I heard that Uncle Bernhard, who lived in Stuttgart until 1943, was sent to the camp Mauthausen with eight other Jews and eight days later the news came that he and five others from the transport were shot as they tried to flee. His ashes were returned and buried in the cemetery “Pragfriedhof” in Stuttgart. But in 1944 exactly this spot was hit by bombs so that I can no longer find the spot. A Jewish woman who is married to an Aryan told me all of this and I definitely believe that it’s true. Now I want to tell you about my humble self.

I was arrested on November 26, 1941. Four days before we had received the order from Stuttgart to pack food and the most necessary things. We were allowed to take along a suitcase of 50 kilos, which was sent away and which we never saw again. In the night from November 26 to the 27 we had to sleep in the gym of Schiller School like dogs without beds or blankets. On the same day we were examined by the Gestapo and all of our money and valuables were taken away. Do you remember Frank, Sauter and Östreicher? These were the fine gentlemen who examined us. On the morning of the 27th we were herded like criminals to the train station. It was still pitch dark and we were accompanied by the hooting of the street urchins and “our” lord mayor Dr. Pack was also there. As a farewell he shouted, “Go to hell, you pack of pigs.” We arrived in Stuttgart and stayed there until December 1. At 4:00 in the morning we were put into train cars at Nordbahnhof and rode three days and four nights in unheated wagons to Riga. We only got water twice on the way. We almost died of thirst before we arrived. When we disembarked we were hit and yelled at like cattle. In 10 minutes there were 28 dead. We got the right impression immediately. To still our thirst we ate ice and snow. We were herded into a couple old barns and sheep stalls and to make it short – that’s where we stayed. We stayed there in the ice and snow until the end of March. In our baracks 18-25 men died every day because they had frozen to death during the night. Many more died of typhus, dysentery and frostbite. At the end of March a transport of more than 2000 women, children and old men was assembled and taken to Dünamünde. Not until later did we learn that all of them had been gassed. And so from the 6000 people in January the transports reduced us to 450 people. We stayed in this concentration camp until March 1943. Then we were in the Riga ghetto for one month and after that we were in the big Riga concentration camp. Already in February 1942 my dear father died of blood poisoning. Within 10 minutes he got frostbite on his hands, feet, ears and nose and because there was no medical assistance whatsoever, his extremities began to decay and two days later he died unexpectedly. It was February 26. One month later on March 26 mother was taken away. We ourselves had to load the people into the cars where they were then gassed. It was a real dog’s life. In rags, unwashed, hungry, full of lice, leprous we went to work day for day. Real drudgery and working in masses. Beatings were a daily spectacle, for the smallest things we got 25-50 on our bare bottoms. A lot of people died as a result.

In these few years we moved around all of Latvia. In June 1944 we were sent to Kurland. We had to walk 260 km in the hot sun without any water; finally I could flee with a few comrades into the “jungle”. We were separated because of the search parties and many of my comrades were shot. And so I roamed through the forest for weeks until the Latvian police arrested me. I was in the Windauer prison for one week and then seven weeks in Liban in an SS bunker. We were half starved and festered when the last transport of Jews from Latvia was brought to the ship in the Liban harbor. In the bunker there were 22 of us prisoners. Every night we had to take turns sleeping; only 11 could sleep at a time and that not easily. It was terrible. Our daily rations were 285 grams of bread, for lunch ½ liter watery soup and in the evening five potatoes of which two were rotten. On October 12, 1944 we arrived in Gdansk, in a new concentration camp called Stutthof near Gdansk. New trouble and oppression. We stayed there for one month. It was the worst. We were driven out of the barracks at 5:00 in the morning and had to stand outside in all kinds of weather – wind, rain or snow – until 8:00. Every morning and evening we received 100 grams of bread and every morning at 10:00 ½ liter soup. After that we went to Gdansk to the submarine shipyard Schickau. It was ridiculous. There were 1000 Jews, 2000 Italians and just as many Poles and Russians with few Germans. We had to build submarines and we had no idea how. We stayed here until the end of January; the Russians were getting closer and we were marched to the concentration camp Lauenburg. In snow and ice with nothing to eat except for three raw potatoes a day and at night sleeping in wet, cold churches we were forced onward. We couldn’t go on, to the left and right of the road people fell into the ditches and stayed there. People who had saved themselves for the last three years, because we were the strongest. Always being struck by the blows of the SS, it cracked left and right, those who really couldn’t go on were put out of their misery by a shot in the back of the neck. It brought tears to the eyes of those of us who had already seen so much suffering and blood with cold indifference. On clear ice, slipping more than walking, in wooden shoes, carrying the SS’s heavy baggage, we crept on. From 4600 prisoners we arrived in a former R.A.D. camp [Reichsarbeitsdienst = Reich Labor Service] on the third evening, where others from concentration camps already were. Our numbers had shrunk to 480. We wanted to continue the next morning, but we couldn’t because there was typhus in the camp. We stayed there for four weeks without bread, only ½ liter watery soup, daily work in the stone quarry. We were down to 120 men when the Russians freed us on March 10. Out of curiosity the Russians weighed us. I weighed only 32 kg, the most was 45 kg in the strongest men. After that we were in a sanatorium for eight weeks, where we slowly recovered with the help of excellent care and food. We were given food five times a day, only white bread, butter, sugar, coffee, plenty of cocoa and nevertheless all of the men except for 30 died and these were released healthy. I myself was almost unconscious for four weeks, ate almost nothing and slept in a bed, which we had to get used to again. After that I reported to the Russian militia. I was trained for three days to use a machine gun and fought against the SS troops and gangs. They felt our vengeance, there was no pardon and there were no prisoners. I swore that for every scar on my back I would kill 10 SS. And I kept my word. At the end of the war I was in many different cities such as Berlin, Leipzig, Bitterfeld, Halle, Dresden, Magdeburg and in Vogtland. Finally I was in a large manor near Magdeburg as an overseer and interpreter because I speak Russian very well. On October 1 of that year I left my troop with many blessings and arrived in Göppingen on October 4. I found a room with Frau Munz née Wassermann where I stayed. On October 10 or 11 I met Mrs. Bernard, who I didn’t know at all, and she arranged for a good position for me with the US military government in Esslingen, where she herself lived. I’m very satisfied with the position and Tante Bernard is very delightful and treats me like her own son. I’m going to stop now, it’s already 11:00, I have to go to bed. I’m sending you a picture of me. Please send these pages on to Aunt Paula and she should send them on to Suse, Doris and Arnold. Please write them that they should send me pictures of themselves and my dear parents as soon as possible. I lost all of them in the concentration camp. Next time I’ll write to you about my current job. Greetings and kisses.

Love, Your cousin Richard

Leave a Reply