Seestr. 6

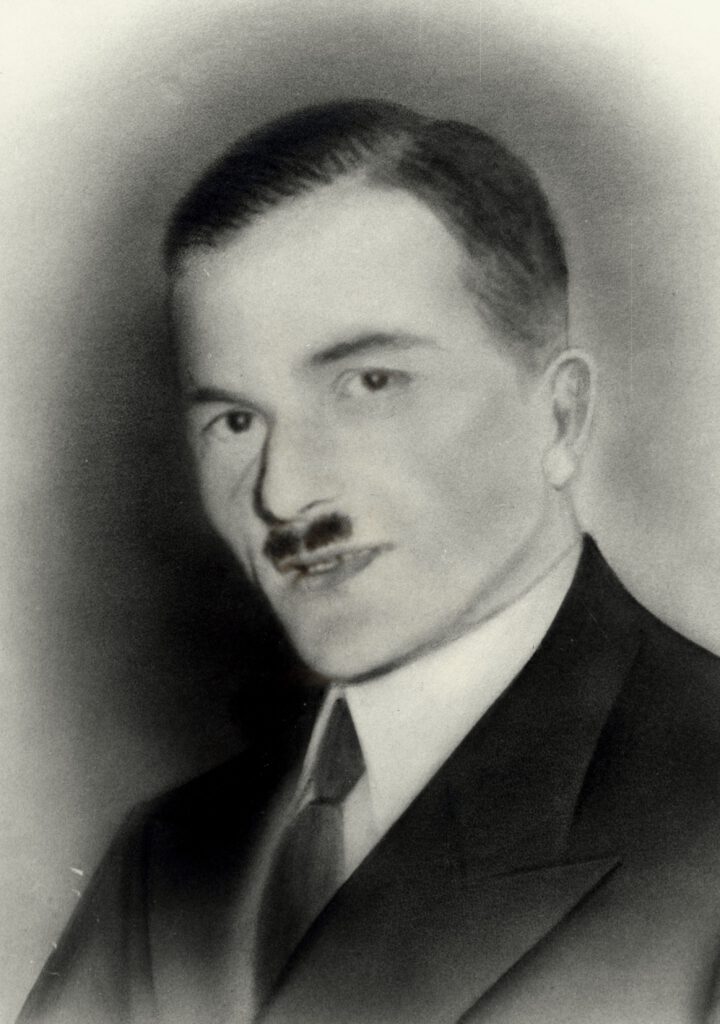

Eduard Löwenthal was born on May 6, 1899, in Pirmasens in the Palatinate, the son of David Löwenthal. His father was a bookbinder and was born on March 15, 1847, in Danzig. His mother was Magdalena Mayer, divorced Schneider. She was born on June 30, 1855, in Burgalben (today Waldfischbach-Burgalben), and worked in the footwear industry. According to known documents, Eduard had three older half-sisters from the first marriage of his mother and an older brother Emil who was born on July 27, 1895. According to family stories, his older brother emigrated to America, but despite his brother’s encouragement, Eduard remained in Germany. Eduard’s parents were divorced on November 24, 1916, in Zweibrücken.

Unfortunately, it was not possible to determine how Eduard Löwenthal came from Pirmasens to Württemberg. He must have lived in Esslingen on Neckar beginning in November 1928, then from May to November 1929 at Gerbergasse 10 in Göppingen. He married Theresia Deibele, a Catholic factory worker from Wäschenbeuren, on November 9, 1929, in Göppingen. And a few days later, on November 27, 1929, their first son, Walter Löwenthal, was born in Sparwiesen.

The young initially lived in Göppingen before moving to Wäschenbeuren around 1930. There the family continued to grow: in 1931 their daughter Pia was born, in 1934 their son Raimund. All three children were baptized Catholic.

Around 1933/34 the young family moved to Pirmasens for four months where Eduard worked as a shoemaker. However, Theresia was so homesick that the family returned to Wäschenbeuren. The family lived there under poor circumstances at Wettegasse 149, but without support from the community. The community-owned apartment where they lived consisted of a room and a small bedroom without a window, the toilet was a barrel. Really modest living conditions!

Eduard Löwenthal was trained as a shoemaker. In the last year of World War I, he had to fight on the front from February 8, 1918, to August 31, 1919, as an infantryman of a Bavarian infantry regiment (the Palatinate was part of Bavaria).

After marrying Theresia in 1929, Eduard Löwenthal wanted to settle in Wäschenbeuren as a shoemaker. However, he was denied permission to do so because “locals had to be taken into consideration first”. From 1930 to 1932 Eduard therefore worked as a laborer for the municipality of Wäschenbeuren. He was unemployed for a year and then worked intermittently for the municipality. Beginning in summer 1934, he always worked in the Jewish cemetery in Jebenhausen during summer. The Jewish community always supported him financially and also gave him gifts.

Between 1935 and 1938 Eduard Löwenthal worked briefly in Göppingen for the Leonhard Weiss Company, the Kinessa Company, the Frankfurter & Bros. Company, the Israelite Congregation and as a carpenter for the Speiser Company.

Because he had a goiter that caused increasing difficulty in breathing, he was repeatedly unable to work.

For a short time Eduard Löwenthal was also the owner of a carnival boat swing (located in Lorch), which was set up in Wäschenbeuren a few times. Before the move to Pirmasens, however, it was sold. At carnivals during 1936-37, Löwenthal operated the boat swing of a Mr. Rebmann on weekends as well as on Pentecost 1938.

On the basis of these facts, it can be clearly demonstrated that Löwenthal was always employed and that he alone supported his family.

Arrest and the Road into Death

On the evening of June 14, 1938, Eduard Löwenthal was picked up at home by police chief Strohm and taken to the town hall in Wäschenbeuren without any prior notice. Theresia Löwenthal: “Strohm came at that time and said that my husband had to come to the town hall because he would be interrogated. Then my husband never came back.” The following day, Strohm took Eduard Löwenthal by car to to the district court prison in Göppingen. When Strohm took him into the prison, he was said to have shouted: “I am bringing the Jew, throw him in jail!”

Eduard’s wife Theresia was worried and inquired: “Strohm did not give me an answer why my husband was arrested.” On June 27, 1938, Eduard was taken from Göppingen to Dachau concentration camp. After about 10 days his wife received a message from him: “I am in Dachau and am healthy: Farewell.”

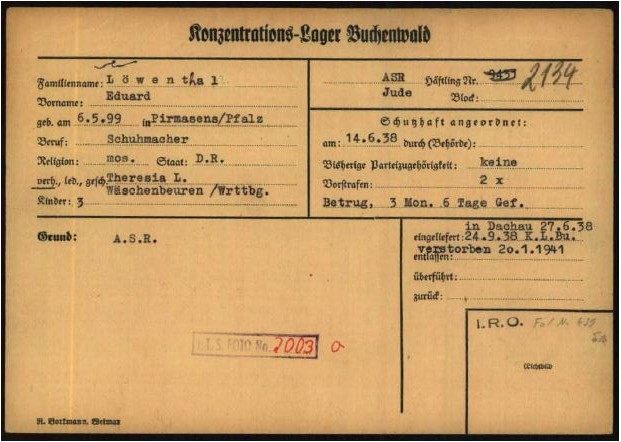

On September 23-24, 1938, Eduard Löwenthal was taken to Buchenwald concentration camp. As a reason listed was: “Does not want to work” and two criminal records for fraud. A total of “3 months and 6 days in prison” were listed as penalty in the records in the commandant’s office.

He was given prisoner number 943, which then was changed to number 2134 after April 20, 1939, and was housed in block 23. Löwenthal had to do hard labor in the quarry as a “rock carrier.” Another serious physical strain was caused by the goiter which was increasing in size.

It is touching how Theresia Löwenthal turned with her concern directly to the commandant’s office of the concentration camp several times to find out what had happened to her husband. Supposedly Löwenthal himself also sent a letter to Father Noll, the Catholic priest of Wäschenbeuren, with the statement: “I hope to be home soon.”

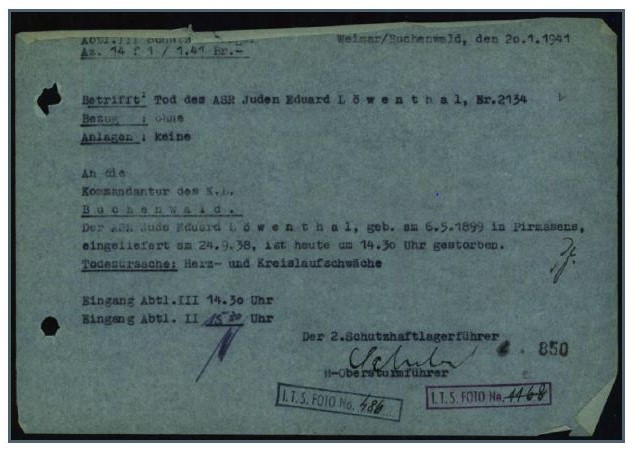

After almost 32 months in concentration camps, Eduard Löwenthal died on January 20, 1941, in the sick bay of Buchenwald concentration camp. The family was informed in a terse letter about the death. The cause of death was listed as cardiovascular weakness. Eduard Löwenthal was only 42 years old.

One can assume that Theresia requested the urn with her husband’s remains from the commandant’s office at Buchenwald concentration camp and therefore the urn was sent from the concentration camp to the town hall in Wäschenbeuren.

It was interred near the northern wall of the Wäschenbeuren cemetery. Today the grave of Eduard Löwenthal is being maintained by the community.

Background of the Arrest

It can be assumed that Eduard Löwenthal was arrested by policeman Hans Strohm as a previously convicted Jew according to order no. 2 of the Reich Police Department from June 1, 1938: From June 13 to 18, 1938, the Nazis led the “mission” ” Arbeitscheu Reich” [“Does not want to work”- note by translator] (also known as the June Aktion). Because of this “Aktion”, 4,000 men were arrested and deported to concentration camps. Of these 4,000 men, 2,300 were Jews. Most of the deportees were forced to work under the most inhumane conditions constructing Buchenwald into the largest concentration camp in central Germany. Hitler himself had ordered the campaign to be carried out in June, in addition to the so-called anti-socials (beggars, vagrants, alcoholics) to also include Jews who had a criminal record and whose sentence had been at least four weeks.

In Eduard Löwenthal’s case, the list of his criminal record may also have played the fatal role: His own application in 1934 for the award of the Cross of Honor for frontline fighters was sent from the Zweibrücken district court to the district office in Welzheim. Mayor Köder of Wäschenbeuren originally supported Löwenthal’s application for the award of the Cross of Honor. Only after obtaining an excerpt from the criminal record through the Welzheim district office did the mayor write that “An approval could no longer be recommended.”

It can be assumed that police officer Strohm also was able to take a look at the list and then use it as reason for making the arrest and that he played the central role in “digging Löwenthal’s grave.”

From 1929 to 1941, Hans Strohm was the chief of police in Wäschenbeuren after having been employed in Ebersbach from 1941 to 1943, and then worked again in Wäschenbeuren from 1944 to 1945. The files from the archive in Ebersbach show that Strohm was a staunch Nazi without actually being a member of the Nazi party. And Strohm even came to the attention of one of his former superiors: Richard Engelmann, later chairman of the court of arbitration, explains: “… particularly arrogant scheming Nazi… notoriously a heavy drinker.”

Strohm boasted that thanks to him, Wäschenbeuren was “gypsy-free” and that no “gypsies” would come there any longer. He was considered the “terror of the gypsies”. This statement proves his disgusting racism, which certainly would also explain his hatred of and his actions against Löwenthal. In the reparation process of 1952, the Catholic parish priest Noll stated as a witness: “But I assumed that he was arrested for racial reasons. This is also confirmed to me by Mrs. L.’s suggestion that Strohm looked at her husband with viciousness.” A Jew was not to be allowed to live in Wäschenbeuren. He had to be removed from the community. And he, Hans Strohm, – one can assume – had to take care of it! It is likely that he he accused Löwenthal of an amoral lifestyle. Strohm claimed that Löwenthal was a drinker, a beggar, had a criminal record and did not want to work. He also slandered him as a bad family man because the children supposedly had to sleep in boxes. All of these nasty accusations were clearly refuted by various witnesses during the reparation proceedings.

The Nazis’ “June Aktion” was apparently a suitable way for Strohm to achieve his goal. He picked up Eduard Löwenthal at his home right after work and allegedly took him to the town hall for questioning. Mayor Eugen Köder and local group leader Alfons Wohlschiess were not present. Köder was supposedly annoyed by the cost of the use of a private car without his permission.

Theresia Fights for the Survival of the Family

Since the arrest of Eduard Löwenthal, the father of the family, in June 1938, there was no longer a breadwinner for the family of five. Theresia Löwenthal was left in poverty with three small children and without knowing what had happened to her husband. She tried to obtain information about her husband and wrote several times to the “administrative office” of Buchenwald concentration camp. She wanted to know how Eduard was doing. However, not a single letter was ever answered.

Theresia Löwenthal (right), son Walter with wife Ingrid

and the two children Eduard and Ehrenfried (from left) (Photo private)

In order to ensure the survival of her children, Theresia Löwenthal worked as a cleaning and washer woman for the Strohm family. She was thus in a dependent relationship, which probably played a role in the restitution proceedings regarding her testimony. According to testimony by Theresia’s daughter-in-law Ingrid, the wife of her son Walter, Strohm threatened Theresia that if she testified against him, he would have her son Walter shipped to the Russian front. It can be assumed that Strohm continued to put her under immense pressure which lasted until well after the war.

Theresia’s son Walter had narrowly escaped being drafted into the military. According to Ingrid, Walter was ordered to the front at the end of the war. But he was very lucky: The train on which he was supposed to be taken the Russia could not get through because the railroad tracks had been destroyed by the bombing of American planes.

The Reparation Proceedings of 1952

The widow Theresia Löwenthal had a hard fate. On the one hand, she had to take on the role of breadwinner of the family after her husband’s death in the concentration camp in 1941. At the same time she had to raise three growing children. On April 19, 1945, she also had lost all her belongings in the bombing raid by the US Air Force on her home town of Wäschenbeuren. She now had to live with her three children in one room (6m long, 3.5m wide), with a kitchen, in the old school house, and she didn’t have any money.

And then, during the reparation proceedings of 1952, she had to fight that it was recognized that her husband’s deportation and murder was because he was Jewish. The legal representative of the State of Baden-Württemberg questioned whether Eduard was deported because of his criminal record or because of his Jewish descent. However, several witnesses testified that the deportation of Eduard Löwenthal had been due to his race and disproved Strohm’s statements. Finally, starting on November 1, 1953, she received a monthly widow’s pension and financial compensation. For example, former neighbor Josef Maier, 73 years old and a pensioner, made the following statement during the reparation proceedings: “I didn’t know why he was arrested, but I thought maybe because he was Jewish.”

Although Strohm claimed that he had to deport Eduard by order from Göppingen, there was no one else in Wäschenbeuren who was considered anti-social and was therefore deported. During the Reparation Proceedings, Alfred Nagel, the county executive director from 1936 to 1943, could not recall that in 1938 any arrest orders of Jews and anti-social or other people were carried out. And the then senior government councilor Dr. Karl Kübler also stated: “It is completely impossible that the Göppingen county office issued an arrest warrant. The county office Göppingen was not responsible for dealing with the cases from another county at all, and it would not be correct that police officer Strohm received his instructions from Göppingen.”

A Special Tragedy

During the denazification process against Hans Strohm, Theresia Löwenthal was also summoned as a witness. In a sworn statement that the lawyers of Strohm presented, she emphasized the support she had received from him. She described that he supported her children and that she did cleaning and washing for his family, and she did not testify against Strohm. Even after the end of the Nazi dictatorship, the long-suffering woman could not escape the pressure he had exerted on her.

Irony of fate: Thanks in part to her testimony, Strohm was found guilty as having only been “ Carrying minor responsibility ” during his denazification process in April 1948 and had to pay 1,000 RM “atonement” penalty. However, the fine could not have caused him much difficulty since a few months later, the currency reform took place. The equivalent of ten Reichsmark was only one Deutsche Mark [new German currency].

Gunter Demnig laid the Stumbling Stones on 10.07.2020 in front of the house Seestr. 6.

(10.07.2020 / at)

Text and photos are based on a brochure published in German in October 2019 with the title: ‘Im Gedenken an Eduard Löwenthal 1899 – 1941’ (‘In memory of Eduard Löwenthal 1899 – 1941’). The authors are Julie and Sarah Löwenthal, co-author is Angelika Taudte. Design: Saskia Staible.

Leave a Reply