Main Cemetery Goeppingen. Jewish Graves

“Ladies and gentlemen, honorary guests, Mister Lord Mayor Till, Mister Lord Mayor Dehmer of Geislingen, dear fellow citizens, dear students, Guenter Kunert, a poet who died two months ago, a contemporary of the dead of Geislingen who we commemorate today and classified by the Nazis as a “half- Jew” combines in his poem published in an anthology in 2002 titled “Menetekel” visionary the past and the present with a projection of the future and thus ask for our response. I would like to read that poem to you:

Menetekel

Stars above. And sown to jackets.

History as a murder case. Lamento of the perpetrators.

The watch shows: A millenium fades away.

And sons turn to be likes of their fathers.

Innocence gone. Too late for remorse.

Nobody calls back the dead back to life.

So we are also gone with the wind,

Although we strive for duration.

Forward into nothing and disaster sown

For generations to come.

The writing on the wall, the poem reveals,

The future will not spare nobody.

The initiators of this memorial project wanted to set again something against the dark prophesy in this city that invites to a discussion about the past.

It is moving to me that these Jewish fellow citizens who rested unknown among ourselves and had to suffer so many deaths can be called back to our memory through the memorial slab. They had to suffer death through attacks, hostile treatment, inhuman behaviour including maltreatment, exploitation till the extermination in a anonymous mass grave. Thus they disappeared even from the eyes of surviving fellow prisoners who were exposed to an often lethal indifference of their fellow people.

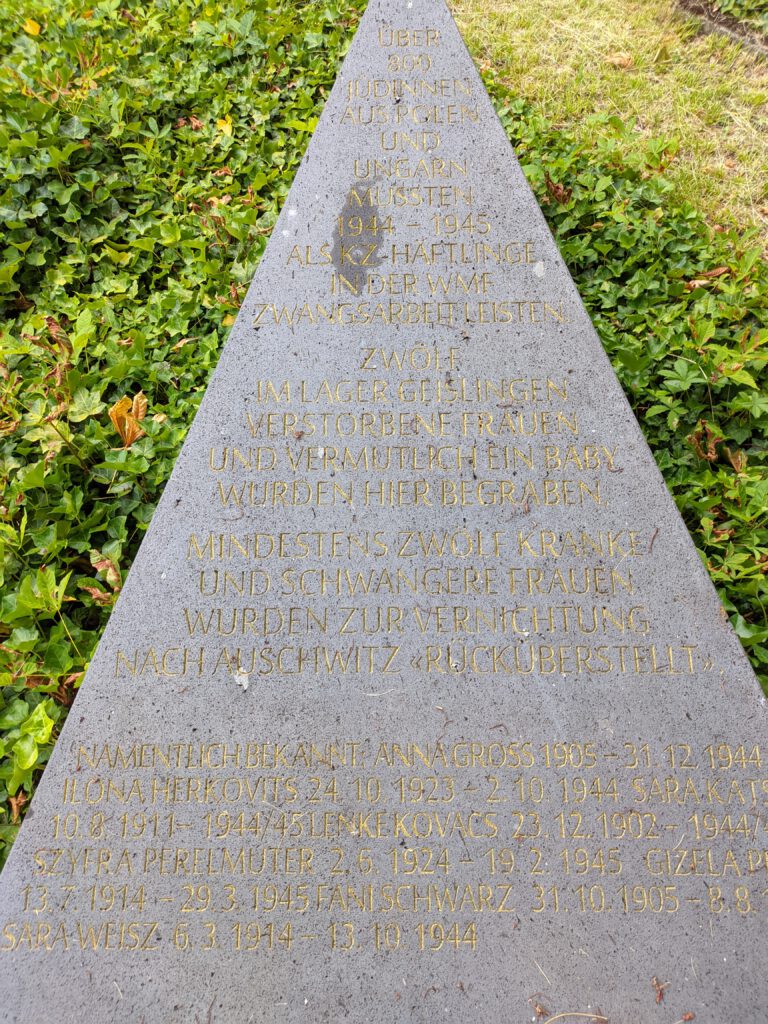

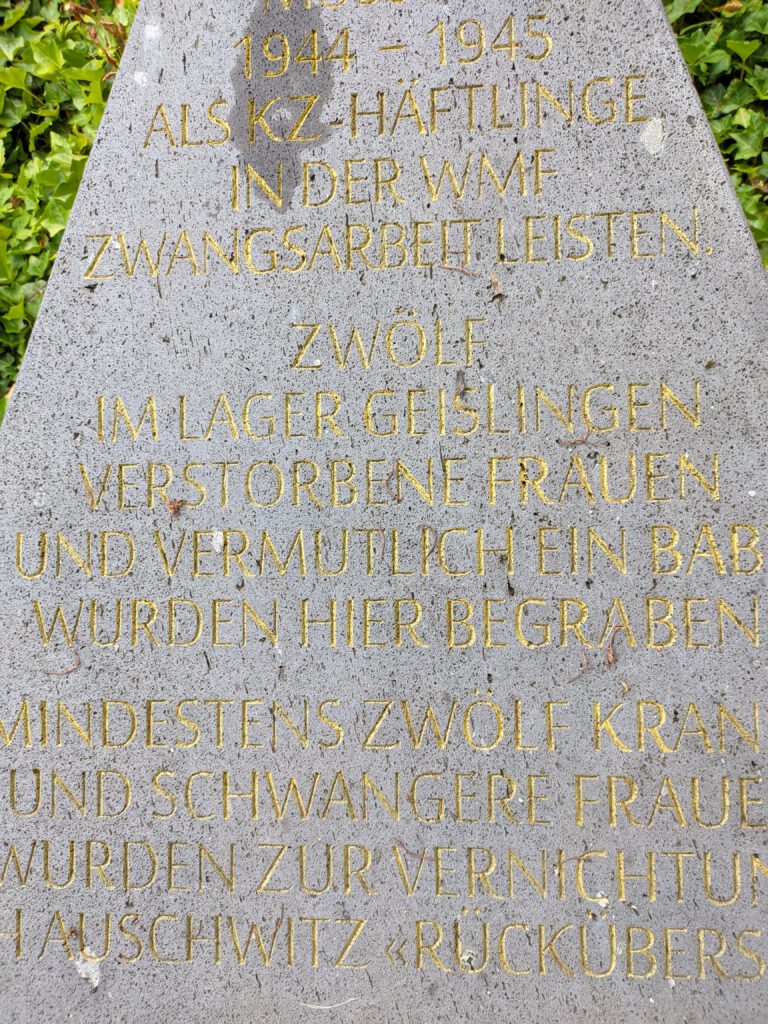

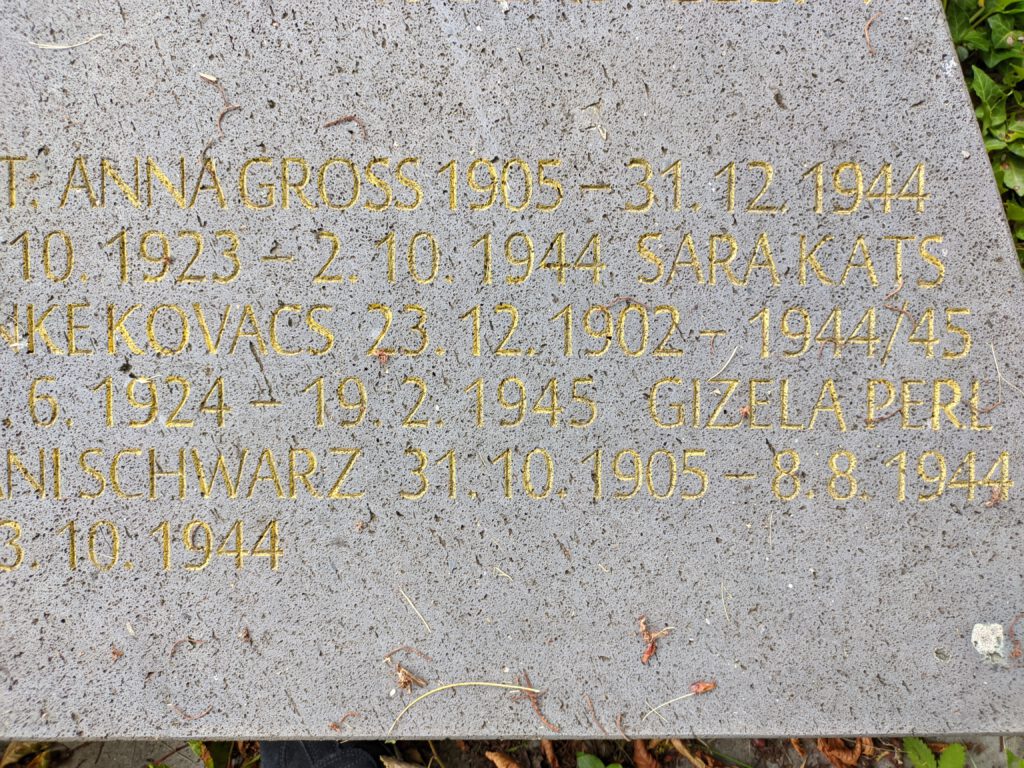

The memory of the position of the graves on the present cemetery was barred. In the important volume on our cemetery by Naftali Bamberger of 1990 these graves were noted as “unknown gravefields without stones of unmarried people from Heidenheim”. Only with the assistance of old documents supplied by Mr. Swoboda, in charge of the cemetery,the nine graves of this row of graves could be located which carry the ashes or the bones of the twelve adult female prisoners who had died in Geislingen.

The first undocumented grave contains the ashes of four Jewish women from Hungary whose corpses were cremated between August and October 1944 in Goeppingen crematorium.

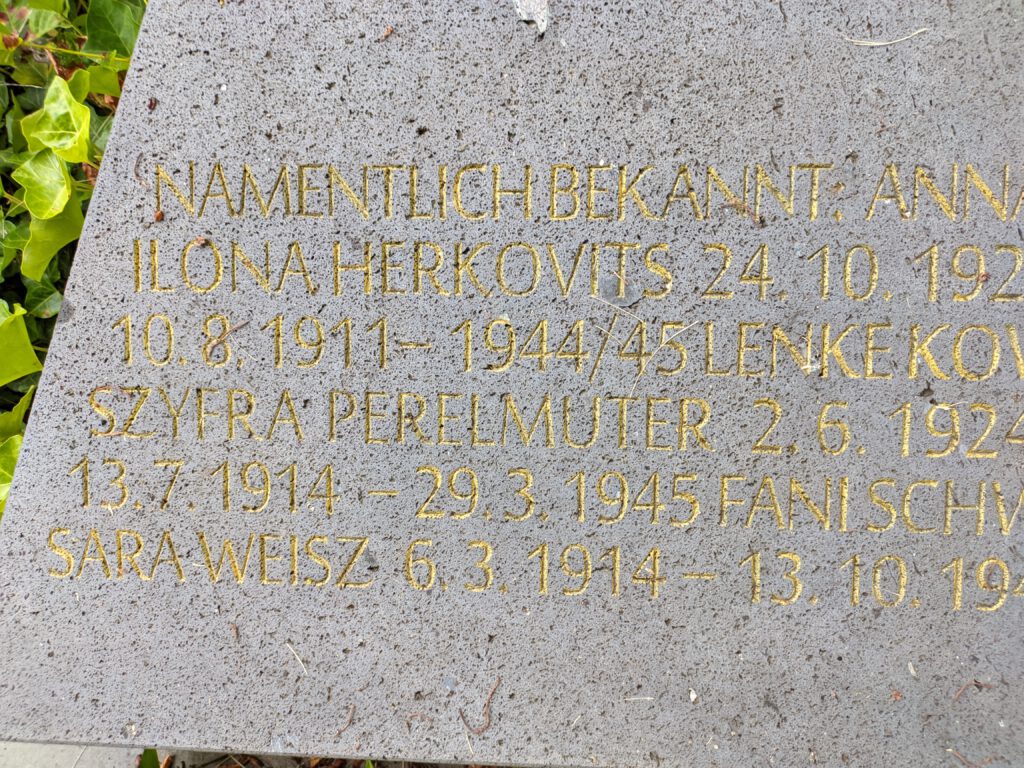

Fani Schwarz died at the age of 38 1944 August 8, shortly after her arrival from Auschwitz, the first one to die, before she could be taken to forced labour in the WMF. Her younger comrades Ilona Herkovits (age 21) and Sara Weisz (age 30) died in October and were cremated and put in the same grave with an unknown Jewish woman. The causes for their deaths are like with the other victims unknown.

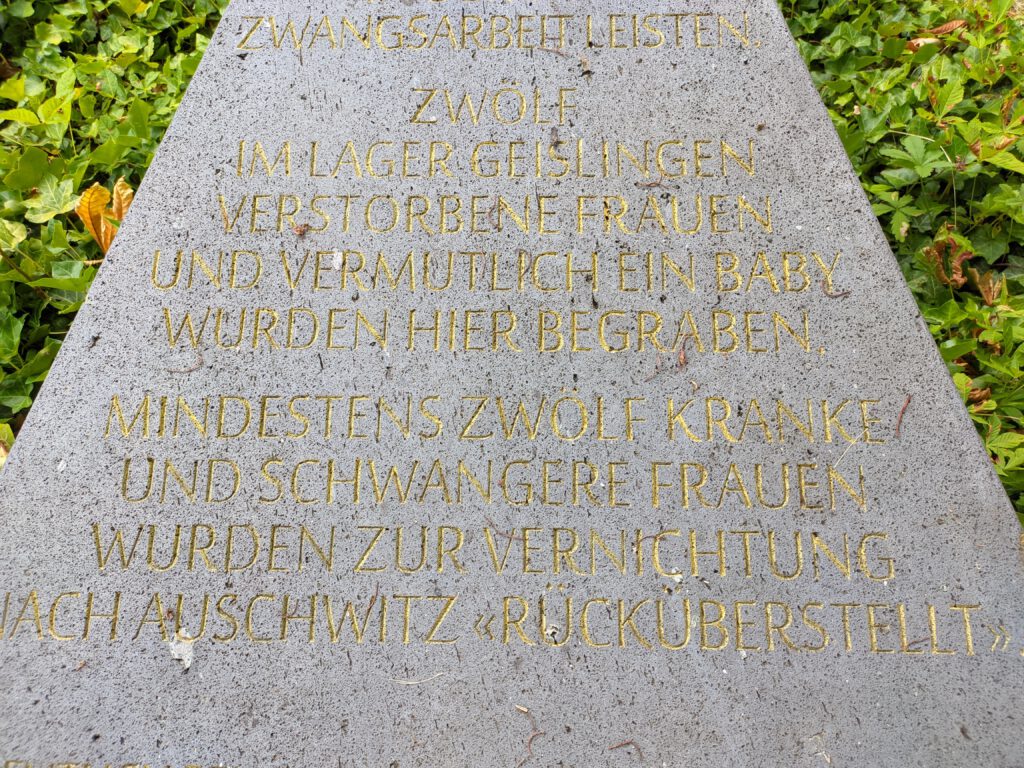

Following the wish of the Israelite Community the corpses of the Jewish forced labour women who had died between December 1st 1944 and April 4th 1945. were reburied into eight single graves. They had been buried in a mass grave on the graveyard wall in Geislingen. Only two of them could be assigned to a single grave, namely Gizela Perl and Lenke Kovacs.

Gizela Perl was possibly identified by her surviving husband who set a sign of memory for her life ended upruptly at the age of 30 by erecting a broken pillar on her grave. Mentioning the death of her son murdered at the age of four in Auschwitz suggests that this tragedy has also contributed to her death as much as the harshness of forced labour and a kidney disease diagnosed by the WMF doctor.

To her right Lenke Kovacs was buried, the Hungarian medical prison doctor, as her prisoner’s number documents in the cementary archives (which was noted against the orders).

Dr. Kovacs is the oldest forced labour woman who died in Geislingen, she was only 42 years old.

Lenke Kovacs was born in a small village in the foothills of the Karpatens where most of the Jewish women who were forced labourers in the WMF came from. Her fate is not knownbut she was deported at about May 1944 after a forced time in a ghetto to Auschwitz and at the end of July she was selected together with 700 women and girls from her home region for forced labour at WMF Geislingen where she was employed in the hospital of the KZ-camp. Her niece Aranka Fogel age 21 was deported with her to Geislingen and reported about an incident that caused trouble for her aunt against the SS and especially against the kitchen capo. Her aunt saw the capo when he was stealing victuals designed for the prisoners. It must have been extremely hurtfull for the doctor to see the scare food smuggled out of the camp in which hunger was vexing her fellow prisoners and weakened them. She must have felt her responsibility to set an end to these activities by a courageous report of the incidents to the SS. Her niece stated in 1948 in court the consequences for her aunt: “One or two days afterwards the kitchen capo came into the block in which I and my aunt were living and slashed with a wip at my aunt, for such a long time until blood was seen and she fell to the ground. I have seen that personally. My aunt later died in the camp. The cause for her death cannot be said but she was often beaten by the Capo.

Other witnesses state a direct link between the maltreatments and the death of the medical doctor. The kitchen capo stated after the war that the accusations were completely unfounded. The company doctor agreed with him and stated that there were no maltreatments or malnutrition in the camp. Only one former pharmacist was helping the sick without appropriate medicine.

In the graves left of Gizela Perl or right of Lenke Kovacs there are three more victims known by name, namely the Hungarian Jewish women Sara Kats (age 33) and Anna Gross (age 39) as well as the youngest and only Polish Jewish woman Szyfra Perelmuter. We know about Szyfra’s fate through the surviving sisters Tusia and Ruchla Kolberg – the photo shows the surviving sisters shortly after their liberation. They come from the same small town in the Lodz area like Szyfra, are almost the same age and were passing through the same stations till the forced labour at WMF (at least since the German occupation of Poland).

In 1939 Szyfra is 15 years old, Tusia one year younger, Ruchla one year older. They suffer from the isolation and deprivation of rights of their Jewish fellow citizens, who were half the population in their home town, they were herded together in a small ghetto district, from where more often male Jews were deported into work camps. In August 1942 all the Jews in the ghetto were herded in the synagogue yard and those able to work were separated from the old ones, the sick and the children. Those able to work, about 1,000 people, the Kolberg sisters and Szyfra were carried on lorries into the closed ghetto Lodz (then: Litzmannsstadt), the remaining 4,000 people among them their familiy members were taken to Kulmhof to be exterminated as they got to know later.

In the Lodz ghetto the three girls shared with one more girl a room and worked as tailors or seamstresses in a workshop for the German army (Wehrmacht) as well as for private companies till the elimination of ghetto Lodz in August 1944. They were deported to Auschwitz together and a few weeks later to Bergen.Belsen. In November 1944 they were taken to Geislingen for forced labour in a group of 120 Jewish women from the Lodz area. Tusia tried to cheer up ailing Szyfra with the hope of the end of the war at hand. When Tusia returned on February 2nd 1945 from work at WMF she only can find an empty plank bed. She does not know where her dead friend was buried.

Another six names of Hungarian Jewish women who have not survived forced labour have been known to us but we do not know whether they died in Geislingen camp or whether they belonged to the twelve pregnant or sick women who were “handed back” to Auschwitz on October 11th 1944 , namely Roszi Klein, Sara Marmelstein, Cecilia Pollal, Ilona Schönbrunn, Etus Tebovits and Piroska Weiszmann.

What happened with the corpse of the only male baby born in the Geislingen camp, born December 17th 1944 who was starved by the SS has not been recorded.

The fates of the “handed back” murder victims as well as the fates of the Jewish women buried here and the starved baby make us aghast. Their deaths has rolled like a stone into the conscience of our town and lies there like a menetekel next to the hundred stumbling stones (Stolpersteine). The presence of the dead people in our society can be enriching. Let us make use of it.

Finally I would like to thank in the name of the Stolpersteininitiative, too, the City of Goeppingen as well as the Federal project “Live Democracy” (Demokratie leben) and further sponsors for the generous support in financing the memorial slab as well as Mr Hosch, chairman of the cultural office (Kulturamtsleiter), and town archivist Dr Ruess. Without his support the project would not have been realized and not without the artist Uli Gsell. I would like to thank them all.”

This text by Sybille Eberhardt was presented at the opening of the memorial slab on November 19th 2019 by herself and students Julia Kunike Melanie Nuding and Amelie Scharnagl.

The history of the KZ Camp Geislingen and the fates of the Jewish forced labour women has been portrayed by Sybille Eberhardt in her book “Als das ‘Boot’ zur Galeere wurde …” (Boot = boat for Lodz = Polish: boat) . (ISBN 978-3-95544-100-5)

(03.12.2019 se / pr)

Am part of the Rohrbacher family of Jebenhausen, contributor of memorabilia to the museum. Will be visiting it Sept. 19 2025…any connections would be appreciated.

Dear Mr. Rohrbach,

wellcome in Goeppingen. I sent you an e-mail yesterday.

Best wishes

Klaus Maier-Rubner (Chairman of Stolpersteine – Initiative)