Schillerstr. 33

On September 1, 1936, Fritz Max Erlanger began his employment as cantor and teacher for the Israelite congregation in Gőppingen. He succeeded Berthold Levi who held both of the positions since 1926 and had retired a few months earlier and moved to Stuttgart. It can be concluded that this was not a normal generational change because of the particular circumstances of that time. Three years earlier, the Nazis had taken over the leadership of Germany. Since the ‘Nuremberg Laws’ had been instituted in 1935, it became the goal of the State of discriminate against and take away the legal rights of Jewish Germans. The hatred of Jewish citizens was not only stoked by the State; many ‘Aryan compatriots’ took it upon themselves to make life difficult for their Jewish neighbors and their children.

The Exclusion of the Jewish Children in Gőppingen

Why did the leadership of the Israelite congregation of Gőppingen decide despite limited financial means to start a school for Jewish children of elementary school age? These children had attended public schools for decades, and if there was a denominational separation, mainly the Protestant schools. The Jewish teachers and cantors functioned first and foremost as religious teachers, similar to the clergy of Christian denominations. (Only a few years prior to this did it become possible for Jewish teachers to enter employment and continue to teach in public school systems. That is why Fritz Erlanger’s predecessor, Carl Bodenheimer, met with resistance from Christian parents, see Stumbling Stone biography Sophie Bodenheimer). Not until November 15, 1938, did the Nazis forbid Jewish children to attend public schools. There is no clear answer why the exclusion of Jewish children from public schools in Gőppingen already took place two years prior to that and who authorized it at first.

But in the view of Jewish children and parents there already were reasons in 1936 that made it advisable to protect the children from ‘the general population’. Hermann Freudenberger, who had fled from Gőppingen, remembers in a letter from 1966: “I could not bear to see how my children were being treated in school.” It depended largely on the decency of the teachers if they stopped the actions of the Nazi youths, and a teacher like Karl Baun who made it clear to his students that their Jewish classmate Erich Steiner was ‘one of them’ was a positive exception. (Karl Baun was a teacher and principal at the previously mentioned Uhland boys school prior to his dismissal by the Nazis.)

Therefore it is likely that the members of the Israelite congregation took it upon themselves to open their own school, and that Nazi authorities then forbade Jewish children of elementary school age to attend public schools. However, Jewish youths in the upper grades and in the vocational schools in Gőppingen were allowed to attend until 1938, were not harassed too much and were allowed to graduate.

The Jewish School in the House of the Rabbi

The Jewish children of elementary school age could not understand why they were being excluded. Doris Rosenkranz (✝), née Rosenfeld, who was born in 1927, remembered that she could still attend public school in Göppingen from 1933/34 and 1935 but that she was most likely “thrown out” in 1936, which remained a traumatic memory for her. She then moved to Stuttgart with her mother and later fled to Switzerland. Herbert Steiner (✝) , who was the same age, has similar memories: “I spent my first school years in the regular public school, but starting in 1936, Jewish children had to go to a separate Jewish school.”

And late Richard Fleischer (✝) who was also born in 1927, described the situation as follows: “My school was located at Uhlandstrasse (today Burgstrasse, Uhland Elementary School – annotation by author). I left the school in 1936, or rather I was removed. My father was informed that I could not remain there under any circumstances. My father sent me to Esslingen” (this refers to the Jewish orphanage and boarding school ‘Wilhelmspflege‘ – annotation by author).

Starting in 1936, many Jewish children of elementary school age attended the newly opened Jewish school in the house of the Rabbi (Freihofstrasse 46) where the ground floor served as their school room. The room became available after the departure of Cantor Levi. Bertha Tänzer, the widow of the Rabbi, lived on the upper floor until December 1937. The new Rabbi, Luitpold Wallach, had found an apartment at Rosenstr. 8.

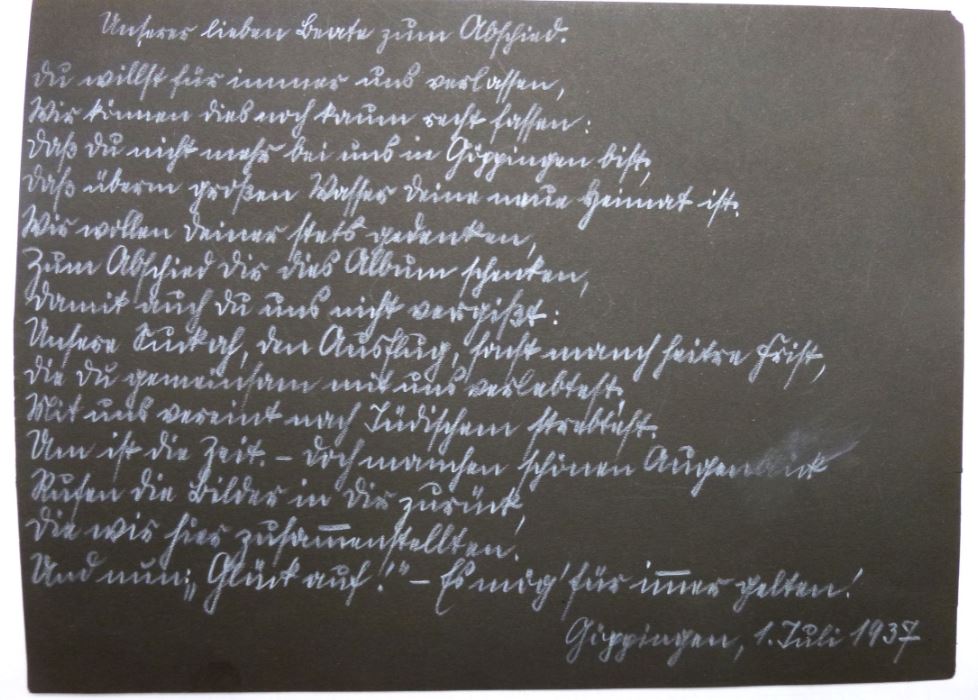

How many children attended the school which did not have separate classes for each grades. Herbert Steiner refers to the time prior to his flight in December 1938: “If I remember correctly, there were approximately 20–30 children between the ages of 6 to 14 in one room.” His classmate Beate Dőrzbacher (later Betty Greenberg), who was also born in 1927, has preserved a poetry album given to her as a farewell present by her teacher Fritz Erlanger in 1937. It contains the signatures of 17 of her classmates.

This number of altogether 18 students female and male corresponds with the number of 17 students which are mentioned in the book of Paul Sauer, ‚Die Schicksale der jüdischen Bürger Baden-Württembergs 1933-1945‘ (The fates of Jewish citizens of Baden-Württemberg 1933-1945) on page 66. Sauer refers to the Amtsblatt des Württembergischen Kultministeriums from November 27, 1937.

Two of the pupils who attended the school at the time lived in Süßen (Ruth Lang and Siegfried Lang) and two in Eislingen (Pnina Plawner and Leo Lerner), the others in Göppingen. Later, probably after November 15, 1938, schoolgirls from the town of Kirchheim/Teck, 20 km away, came to the Göppingen school after they had been forced to leave the general school there. It is known that Renate Reutlinger * 30.07.1930 and Ruth Vollweiler * 30.09.1927 took the bus from Kirchheim to the school in Göppingen.

fleeing the Nazis (Source: US Holocaust Memorial Museum)

(Source: Staatsarchiv Ludwigsburg F 176 II Bü 767)

These new additions confirm that lessons were able to continue after the pogrom night, at least after teacher Erlanger’s release from Dachau concentration camp. It is unclear whether the rabbi’s house, which was not destroyed during the pogrom night, continued to be used as a classroom. School activities in the rabbi’s house must have ended by June 9, 1939 at the latest, as this was when the town of Göppingen acquired the building, which according to the address book remained unoccupied. It is unlikely that the Nazi city administration had allowed Jewish children to be taught in ‘their’ building. However, as there are indications that classes were still being held until 1940, the Jewish school must have found another classroom. After December 1940, when the Jewish child Inge Auerbacher turned six, the Jewish school in Göppingen could no longer have existed, regardless of the location, as Inge had to travel by train to Stuttgart to attend the only Jewish school in the surrounding area.

In the Jewish school, the children were protected from unjust teachers and spiteful classmates. However, the brutal reality caught up with them outside the school and home. Herbert Steiner writes from painful experience: “The direct route to school from Bahnhofstraße 6 was not very long, but the detours I had to make to avoid the stones thrown by the other schoolboys made it a serious undertaking. The bus journey to Göppingen was also threatening for the Eislingen child Leo Lerner. He was regularly mocked and attacked on the way to the bus stop in Eislingen.

Of the 19 pupils known to us from the Jewish school in Göppingen, 14 were able to flee with their families; five children were murdered by the Nazis: Pnina Plawner, Lisa and Doris Rödelsheimer, Inge Banemann and Hilde Stern.

“Fritz Erlanger Was a Very Well-Liked Teacher”

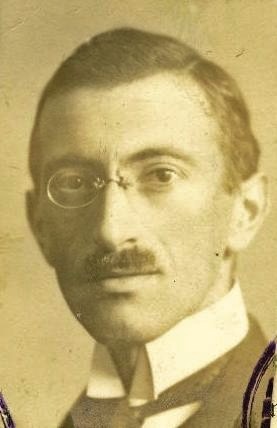

When he started his teaching positing in September 1936, Fritz Max Erlanger was just 23 years old. The teaching position in Gőppingen was his second permanent job after teaching for three years at Esslingen ‘Wilhelmspflege’. Following his teacher’s certification exam in 1933 he held short-term positions in Tűbingen and Rottweil. According to some of the recollections by his students, he must have been a gifted pedagogue. Herbert Steiner remembers: “Fritz Erlanger was a much-loved teacher who understood children very well. Rabbi Wallach never had the same good rapport with us, but one has to recognize that the times were becoming more and more difficult and that he also had other duties.” Betty Greenberg has positive memories as well: “I only have vague memories of Mr. Erlanger, but he certainly was a nice young man.”

The photo must have been taken before May 1933,

because from this point onwards, Jews were forbidden

to visit the baths by a decision of the local council.

(Source: Geschichtswerkstatt Tübingen)

Fritz Erlanger must not only have been likable, but must also have possessed in-depth and broad knowledge. Herbert Steiner remembers: “The subjects taught at the Jewish school were ‘normal’, but of course the classes could be a bit chaotic since there was only one teacher for approximately 30 students in all grade levels. When I arrived in America in 1939, I had a better background in mathematics than most of the children here, but I knew no English, and religious education did not play a big role either.”

The ‘Israelite Weekly Newspaper’ of March 16, 1938, describes a parent conference at the Jewish school at which Fritz Erlanger outlined his teaching goals: “He warned about professions that had been available to our young people before, in which they now could no longer expect to succeed anywhere in the world. Today’s opportunities existed only for manual laborers, especially craftsmen and farmers, and those also only after extensive training. The speaker then detailed educational opportunities existing here and abroad and especially mentioned Hascharah and Youth-Alijah (preparation for emigration to Palestine – annotation by author).“

There is an indication that Fritz Erlanger continued to perform the duties of his position as cantor, according to a notice in the ‘Israelite Weekly Newspaper’ in April 1937: “On March 27, the board of directors of the congregation organized a Seder Evening jointly with the Jewish school and the local Zionist group. Rabbi Dr. Wallach (Laupheim) and teacher Erlanger conducted the service in an exemplary and moving manner.”

When the synagogue was burned down during the night from November 9th to 10th, Fritz Max Erlanger was one of the Jewish men who were arrested and on the morning of November 12th were transported to the Dachau concentration camp. His incarceration there lasted until December 5th. The entry in the registration book at the concentration camp listed Fritz Erlanger’s profession as ‘teacher’ and it also showed that he had no longer been living at Schillerstr. 33, his first address in Gőppingen. Because the address listed in 1938 – Wilhelm Murrstrasse 30 (today Mőrikestrasse) – was a ‘Jewish House’ where people were forcibly being housed, the Stumbling Stone was laid at the location of the earlier address at Schillerstrasse 33.

We were surprised to learn that Fritz Erlanger was mentioned in a letter from August 1940. Hanne Leus, a Jewish woman living in Stuttgart, wrote to the administration of the Gőppingen sanitarium ‘Christophsbad’ where her mentally ill sister Charlotte Schulheimer was housed. The letter disclosed that ‘Teacher Erlanger’ frequently would make a small sum of money available to her ill sister. Mrs. Schulheimer was murdered in Auschwitz in July 1942.

Fritz Max Erlanger continued to live in Gőppingen until the middle of 1941. Probably he had to perform forced labor, but we do not know any details.

Childhood and Youth as an ‘Orphan Separated from his Parents’

Fritz Max Erlanger is remembered as a cheerful, self-assured man, and this was also evident later in his life. One would expect that he came from ‘well-ordered family circumstances’, but that was not the case.

His parents, his mother Anne Therese, née Dessauer, and his father Hugo Erlanger, separated when Fritz, their only child, was eleven years old. This separation ended Fritz’s family life because he was sent to the ‘Wilhelmspflege’ boarding school in Esslingen previously mentioned. His parents left Pfarrkirchen, the town in Lower Bavaria where Fritz was born on March 31, 1913, and returned to their respective hometowns. Hugo moved back to Buchau at Lake Federsee, where he was a merchant in textiles and tobacco goods. He died relatively young in January 1937 at a hospital in Ulm. Anne Erlanger wanted to move back with her parents in Tűbingen who lived there in a wealthier section of the town where Fritz frequently visited her. After Fritz moved away from Gőppingen in July 1941, he was registered once again as living at his mother’s address in Tűbingen for one month.

Hannover – Ahlem: Working as a Teacher Again!

Beginning on August 12, 1941, Fritz Max Erlanger was registered in Ahlem near Hanover where he took a position as a teacher at an Israelite Horticultural School. This institution was established in 1893 when Hanover banker Alexander Moritz Simon wanted to give educational opportunities to the children of eastern European Jewish immigrants. Young men (apprentices) were trained there as gardeners or craftsmen, such as shoemakers and tailors, young women could receive domestic training. There also was a section in the school for elementary age students. The school was basically a boarding school. When Fritz Max Erlanger accepted the position there, the Horticultural School was one of the last remaining Jewish educational institutions in Germany. Since Jewish children were no longer allowed to attend public elementary schools, the number of children in this part of the Horticultural School had increased considerably. In 1940, there were 109 elementary age children attended out of a total enrollment of 240 students. The records from that time show that “…109 boys and girls are being taught by eight teachers.” Fritz Erlanger became part of the faculty with Leo Rosenblatt as the director. A reference to his working there was recorded in the minutes of a school conference on October 2, 1941, “Under the chairmanship of Director Rosenblatt, Ahlem teachers Karl Waldmann, Friedrich Haas, Fritz Erlanger and Meta Schloss held discussions with colleagues from Hanover…”

Edeltraud Lapidas Came Into Fritz’s Life

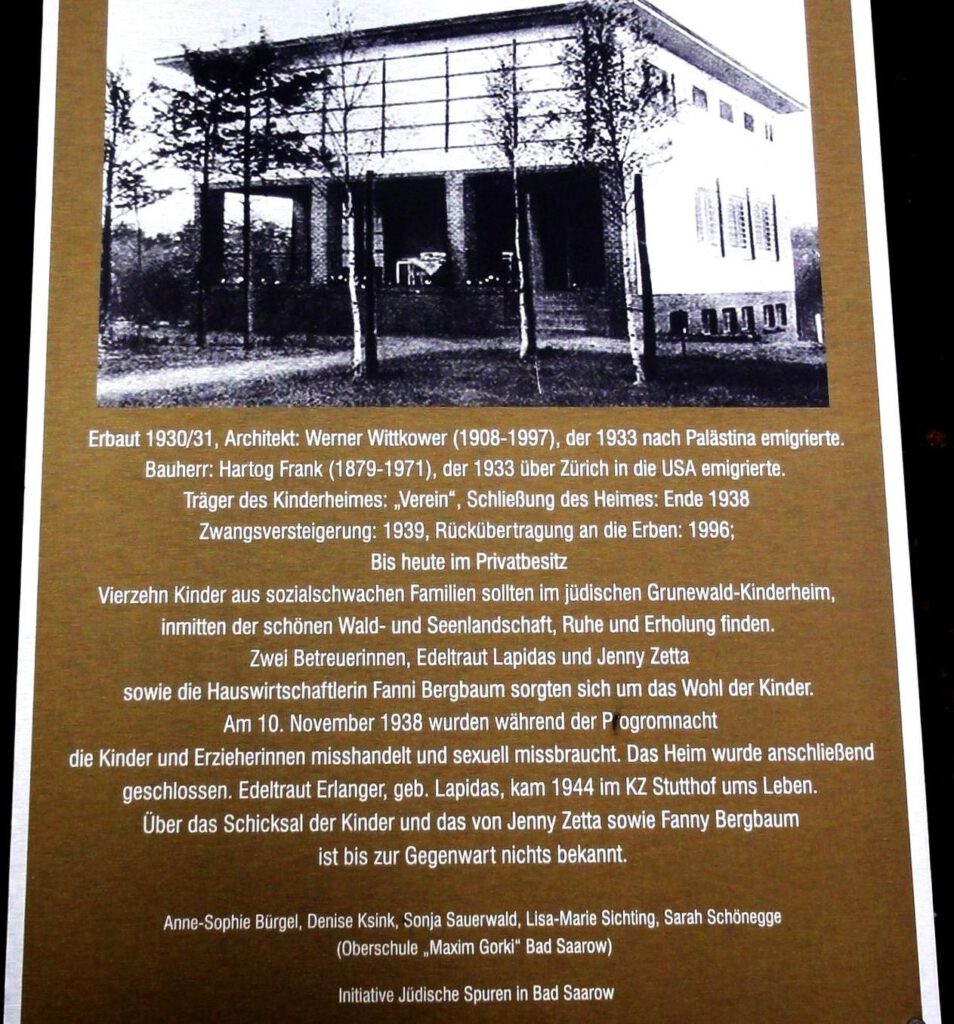

Love at first sight? It appears that Edeltraud Lapidas and Fritz Max Erlanger had only known each other for three weeks when they married on November 4th in Ahlem because Edeltraud had just recently moved from Berlin to Ahlem on October 20th 1941. Edeltraud Lapidas, born in Rőssel / East Prussia, was only a few months younger than her husband and also was a teacher. It is not known if she also was employed at the Horticultural School or why she came to Ahlem at all, but the address of her residence was listed at the school. Until the Pogrom Night, Edeltraud had been the director of the Jewish Grunewald Children’s Home in Bad Saarow, where 14 socially disadvantaged children could find rest and recuperation. After that she had worked at a Jewish hospital in Berlin, and from June 1940 until October 1941 she had to perform forced labor at the Siemens-Schuckert Company in Berlin. Unfortunately no photo of Edeltraud Erlanger exists, but her prisoner personnel record from 1944 described her as follows:

Heigh: medium; Face: round; Eyes: brown; Nose, Mouth and Ears: normal; Hair: black.

Was it even possible for Jewish men and women to still be married officially in Germany at the end of 1941? In any case, all later documents list Edeltraud and Fritz as a married couple.

Riga, Stutthof…

At the beginning of December 1941, a directive from the NS-Reichsicherheitshauptamt [Nazi NationalSecurity Headquarters] to Gestapo headquarters in Hanover requested that the deportation of 1000 Jewish men and women be initiated. The destination was to be the Latvian town of Riga, specifically the Jewish ghetto there, which had been the site of a horrific crime shortly before: at the beginning of December 1941, 27,000 Jewish men and women had been shot there by German security police and SD Einsatzgruppe A. In this manner, ‘room’had been made for Jews who were to be deported from the ‘Reich’. Therefore the newcomers lived in the apartments of their Latvian fellow Jews who had been forced to abandon their living quarters at a moment’s notice. Because of this, they were constantly being reminded of their murder.

Ironically, the collection point where the deportations from Hanover were to start was the Jewish Horticultural School. The facilities there were not at all adequate to house . 1,000 people for days, for example, some internees had to sleep on straw bags in the greenhouses during the cold of winter. The transport from Ahlem began on the morning of December 15. Men, women and over 100 children were loaded onto trucks and driven from Ahlem to a special loading zone at the Lindener railroad station Fischerhof. After three days of torture, the transport reached the ghetto at Riga. Edeltraud and Fritz Erlanger were also on this transport.

The ghetto in Riga was dissolved starting in summer 1943, and the inhabitants still living there were relocated to the Kaiserwald concentration camp. When the Soviet troops were advancing, that concentration camp was also evacuated, and starting in August 1944, the tormented prisoners were moved to Stutthof concentration camp near Danzig (also see Stumbling Stones biographies of Rosa and Flora Frank). Edeltraud and Fritz Max Erlanger arrived there on October 1, 1944, and a prison personnel record for Edeltraud is the last confirmed sign that the couple was still alive. It was almost a miracle that they were both still alive because only 86 of the original 1,001 people from Hanover survived the transport. We do not know if Edeltraud and Fritz were still able to be in contact with each other in Riga and Kaiserwald, and their hope for surviving together might have given them strength. We do not know anything about the last months of the couple’s lives. There are reports that prisoners from Stutthof concentration camp were sent on death marches. Maybe Fritz Erlanger was able to escape, which might explain the following story handed down in his family. Dr. Lothar Dessauer, a cousin of Fritz’s mother, made the following statement in 1971:

“I remember that my deceased cousin Hermann Levi told me many years ago that Fritz Erlanger was inadvertently shot by the Russians when he and his comrades tried to get food from some farmers. Supposedly this information came from one of Fritz Erlanger’s fellow sufferers whose name I understandably do not know.”

Murdered Family Members

Sadly, Fritz Max and Edeltraud Erlanger were not the only members of their families who were murdered:

Fritz’s grandmother on his father’s side, Luise Erlanger, née Neuburger, who lived in Bad Buchau, succumbed on September 2nd, 1942, at the age of 86 due to the inhumane conditions at Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Fritz’s mother, Anne Erlanger, née Dessauer, was first forced to move from Tűbingen to Haigerloch in October 1942. From there, this poor woman who was very ill with cancer was moved to a clinic in Fűrth. A few months later she was taken from Nuremberg to Theresienstadt, where she died on September 30th, 1942.

Anne’s brother and Fritz’s uncle Ernst Nathan Dessauer, who lived in Hamburg, was murdered on January 21st, 1942, at the Litzmannstadt (Lodz) ghetto. A Stumbling Stone has been laid for him in Hamburg-Altona.

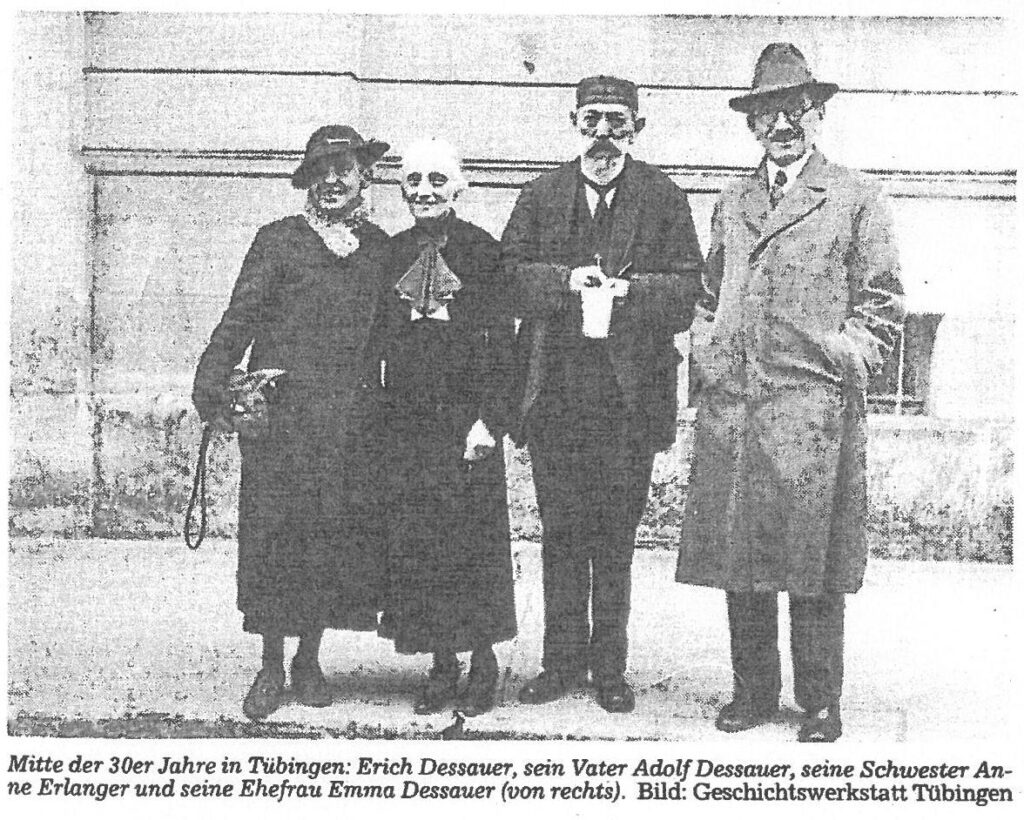

Another brother of Anne, Dr. Erich Dessauer, an attorney in Stuttgart, was murdered on October 16th, 1944, at Theresienstadt concentration camp. A Stumbling Stone in his memory was laid in Stuttgart. His wife Emma was fortunate enough to have survived this place of horror. After the war she opened a bookstore and newspaper distributorship in Stuttgart.

Anne’s twin sister Julie Babette Berger, who had been a grocery merchant and had lived in Berlin, was murdered in December 1942 at the Auschwitz extermination camp.

The family of Edeltraud Erlanger, née Lapidas, was also exterminated by the Nazis:

Her father, Samuel Rischmann Lapidas, died in May 1942 at Litzmannstadt ghetto. In October 1941, Edeltraud’s mother, Erna Ernestine Lapidas, also died there. Two months later, the life of Egon Julius Lapidas, Edeltraud’s 18-year-old brother, also ended there.

A Stumbling Stone in memory of Fritz Max Erlanger was laid on October 2nd, 2013, in front of his former residence at Schillerstrasse 33 in Gőppingen. Three students in the 10th grade at Gőppingen’s Uhland Secondary School, Pervin Tango, Alina Ortner and Kathrin Bader, had prepared a speech that was given during the ceremony. Mrs. Sarah Erlanger came from Zurich to represent the Erlanger family. She was able to describe the fate of her branch of the family.

Sarah Erlanger tells about her family.

A Stumbling Stone for Fritz Max Erlanger was also set in Esslingen / Neckar, Muelbergerstr. 146, as Fritz was a teacher at ‚Wilhelmspflege‘.

The Stumbling Stone Initiative would especially like to thank Richard Fleischer (✝), Betty Greenberg, Doris Rosenkranz (✝), Eric Steiner (✝) and Herbert Steiner (✝) for sharing their memories and many photos. We would also like to give special thanks to the Tűbingen History Workshop and Mr. Martin Ulmer for the best photo still in existence on which Fritz Max Erlanger can clearly be recognized. Mr. Christian Pietà, a member of the ‘Initiative Jewish Traces in Bad Saarow’, researched most of the pertinent information on Edeltraud Erlanger, née Lapidas.

(14.01.2026 kmr/wb)

Leave a Reply