Poststr. 18

Except for a few archival data and a short mention in a letter we were not able to find out much about the lives of the married couple Ida and Julius Löwenstein. But that does not keep us from remembering them and at least to deal with the circumstances under which they lived.

They both came from families with many children, and both of their fathers were merchants. The parents of Julius were Heinrich Löwenstein and Sophie, née Liebmann. Julius was born on May 29, 1868 in Göppingen, followed by two brothers and two sisters. His father was the owner of a grain business which had been founded by Julius’ grandfather in 1867 in Jebenhausen. The business was moved to Göppingen already during the following year. In 1870 Heinrich Löwenstein bought the building at Poststraße 18 which had been built in 1856 by Gottlieb Braun, a butcher. It housed the living quarters as well as the business of the Löwenstein family.

Ida Löwenstein, née Gunz, was born on May 25, 1875 in Augsburg. Her parents were Nathan Gunz, a merchant, and Wilhelmina (Mina), née Feist. Nathan had a leather business in the Fugger house in Augsburg. She was the fifth of six siblings; she had three brothers and two sisters. Salomon Gunz, her father’s brother, was a banker in Augsburg. He and his wife had seven children, five daughters and two sons. Therefore Ida was surrounded by many children. Augsburg had a big Jewish community and from 1913 to 1917 a large synagogue was built which survived the Pogrom Night in 1938 with only slight damage. After World War II it was restored and today it is one of the most beautiful synagogues in Europe. This is being mentioned to give an idea of the self-confidence Jewish people felt prior to World War I.

The date of Julius and Ida Löwenstein’s wedding is the next piece of information which we could find. On March 8, 1900 they were married in Augsburg. Julius was the oldest of five siblings and worked as a partner in his father’s business. That is why the young couple had found a residence in Göppingen; their first home was at Marktstraße 27. They moved twice before moving into the parental house in the years between 1924 and 1927 at Poststraße 18. Julius’ father died in 1916 already, his mother 1922. Julius was now the sole owner of the business.

The couple remained childless. We do not know how they lived, with whom they associated, and what their interests were. They had relatives in Göppingen. Julius’ sister was Selma Hilb, the wife of Emil Hilb, who was a merchant and manufacturer of mattress covering fabrics. In 2012 we installed a Stumbling Stone for him and his family in the Frühlingsstraße. Albert Löwenstein, a brother of Julius, was married to Gisela, née Dörzbacher and had moved at the beginning of the 1930s his grocery store from Kirchstraße 31 to Geislinger Straße 6. Ida’s cousin Amalie lived in Göppingen too and was married to Ludwig Eisig, son of a factory owner. In 1936 Amalie and Ludwig emigrated to Switzerland and later to San Francisco. Amalie Eisig was related to Hedwig Frankfurter. It can be assumed that the local Jewish families of Göppingen knew each other and that many of them were related to each other.

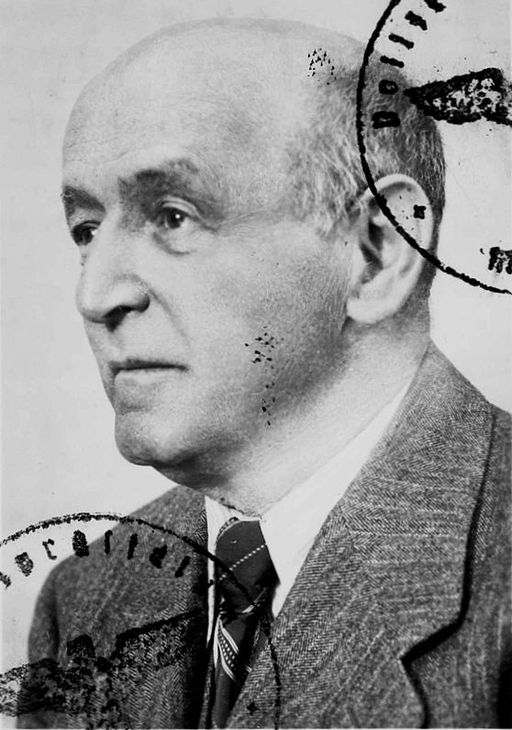

The man and woman on the left are probably Julius and Ida Löwenstein

In June 1933 Ida and Julius Löwenstein moved to the ‘Wilhelmsruhe’, a Jewish senior citizens home in Sontheim near Heilbronn. We do not know what led to this. Was it on pressure that forced them or was it a decision they made of their own free will? Did the grain business in the industrial city of Göppingen have out-dated? Julius was 65 years old, Ida was 58. Hitler had come to power half a year before that and immediately afterwards the boycott measures and defamation of Jewish citizens started. It is understandable that under these dangerous prospects for the future they might have preferred to withdraw from an active life and to be among their own people. In 1934 Julius Löwenstein sold his house to his brother-in-law Emil Hilb.

The Senior Citizens Home ‘Wilhelmsruhe’ in Sontheim

Sontheim, today a part of Heilbronn, was a community with Jewish traditions dating back centuries. When the Löwenstein´s moved in 1933 to the senior citizens home ‘Wilhelmsruhe‘ in Sontheim, it still would have been considered a respectable location. It had been built in 1907 according to plans drawn up by two Stuttgart architects in a combination of baroque and art nouveau styles. It was planned to house 32 people in 20 single- and six double rooms. There was a reading room, a dining- and a prayer room which had been a special gem. There were two medical directors, Dr. Willy Flegenheimer and Dr. Julius Picard. At that time it was not unusual that the German emperor’s name was chosen as the name of the home. Citizens of the Jewish faith considered themselves German – just like those of the Protestant or Catholic faiths. The denomination did not have to be specifically listed on the applications and conditions for admission. The home was considered a residence for ‘old Württemberg citizens who were no longer able to earn a living, in exceptional cases also for ‘Reichsdeutsche’ (Germans from other parts of German Reich) or foreigners‘.

In 1932 open verandas at the back of the building were converted into rooms so that 48 persons could now be housed there. In the years 1936/37 another expansion took place which created an additional 30 single rooms. For most people the acceptance at ‘Wilhelmsruhe’ was probably at first a relief. Because we know of no personal statements the Löwenstein´s supposedly made, a statement by another resident from Göppingen will be used instead. Bertha Tänzer, wife of the Rabbi Aron Tänzer, who deceased in 1937, wrote the following in December 1937: “I am glad to have everything behind me, and, God willing, will be able to live in peace and quiet.” She felt comfortable in her “cosy little room” and considered the refined atmosphere as protection from “the rough outside world.” Unfortunately this peaceful time came quickly to an end. The pressure to accept more residents increased rapidly, and in 1938 one hundred old people were living at the home.

Bertha Tänzer wrote to her son in October: ‘Here is no place for young people any longer, everything is becoming more MISERABLE‘.

During the Pogrom Night of November 9/10 or during the following day the residents of the home witnessed terrible events. Sister Johanna Gottschalk, the home’s director, and a non-Jewish staff member shared their memories years later: nine or ten men knocked down the front door with hammers and axes then demanded that the director should turn over all cameras; after that they cut the telephone lines and proceeded systematically from floor to floor to smash furniture, dishes and wash basins. The next morning not a single window was left intact; groceries and about 300 jars of preserves were dumped into a heap and all lamps and light switches were demolished. During the following days the residents were subjected to gawkers who enjoyed seeing the destruction and took photos of it.

After the November Pogrom the residents were harassed even more, because a Rabbi was no longer allowed to officiate at religious services in the home. The residents took matters into their own hands and conducted the services themselves. Bertha Tänzer was one of those who volunteered.

Following the start of the war in 1939 ‘Wilhelmsruhe’ became the destination for Jewish refugees from the Palatine and Saar regions. In mid-November 1940 the crowded building had to be cleared by order of the NS-Kreisleiter (Nazi county administrator) in charge. It was supposedly needed for ethnic Germans from the Eastern regions who were ‘being brought home into the Reich‘. A portion of the Jewish residents of the home were relocated to the house of Max Picard, the Jewish doctor who emigrated himself one month later. The remaining residents were split up among other Jewish senior citizens homes in Württemberg or had to find a place to live in their former hometowns.

Hedwig Frankfurter, who was mentioned earlier and who was a distant relative of Julius Löwenstein, wrote in a letter on June 29, 1941 that the Löwensteins stayed in Sontheim and were able to move to the house of Dr. Picard. Hedwig wrote to Amalie Eisig in Switzerland on 29 of June 1941: ‘Your cousin Ida and her husband are living in the house of a doctor here in town together with about 14 other pensioners. Julius was fallen very ill, recently very seriously, but seems to be doing better now.‘

In another letter dated September 3, 1941 Hedwig listed the names of Jewish people from Göppingen who had become impoverished, and among them she named the Löwenstein´s. It is not known who took care of the sick after the departure of Dr. Picard. The last doctor who began taking care of ill residents in January 1942 committed suicide on April 23, 1942, probably because he feared deportation. Julius Löwenstein died on November 2, 1941. He was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Sontheim, but no tombstone exists. It is possible that nobody could take care of this, because of the upheavals taking place during that time and because no funds were available.

Ida continued to live in the Picard house. On August 20, 1942 she and the remaining residents were deported via Stuttgart to Theresienstadt Ghetto Concentration Camp. Neighbours observed when the transport was assembled ‘there were many tears and farewell scenes. The last residents of the home were loaded onto a simple wagon and a Miss Israel, who was unable to walk or was paralyzed, was lifted on a stretcher onto the wagon.‘ A man was beaten because a pair of nail scissors was found in his luggage. The reason for the deportation given was ‘re-settlement in the east’.

An especially cruel action by the Nazi-regime against the old people was instituting ‘Home sale contracts’. In these contracts it was suggested that they would be paying for life-long housing, living assistance and being taken care of when sick – and that this would take place in appropriate establishments for old people. The costs were calculated for a life expectancy of 85 years and could be paid in cash or securities. If they refused to sign such a home sale contract they were threatened with forced labour or deportation. Starting on July 1, 1941 all existing contracts had to be converted into home sale contracts by order of the Nazi-regime. The well-to-do residents of the senior citizens home were forced to finance the support for the ones who were indigent as well. The minimum amount for new admissions was RM 11,000. We do not know if these contracts were recognized by the residents as the fraud they were, or if they represented a last hope for them.

Ida Löwenstein’s last fateful journey on which she was taken with the remaining residents of the Sontheim senior citizens home ended on September 29, 1942 at the Treblinka extermination camp after they had been interned for one month in the Theresienstadt Ghetto. The date of her death is not known.

Many relatives of the Gunz and Löwenstein families were murdered in German Ghettos and Extermination Camps:

Ida Löwenstein’s brother Nathan Gunz with his wife Else, who were living in Munich, were deported to Kaunas on November 20, 1941 and murdered on November 25, 1941.

One cousin of Ida, Hedwig Epstein, née Gunz, who lived in Augsburg, was deported to Theresienstadt on 5th of August 1943 and died under the murderous conditions on 28th of March 1944.

Another cousin of Ida, Irene Gumprich, née Gunz, who was living in Schmalkalden, was deported to Theresienstadt on April 19, 1943, murdered on February 29, 1944.

Yet another cousin, Rosa Schnell, née Gunz, living in Augsburg, were deported together with her husband Hermann Schnell on July 23, 1942 to Theresienstadt. Rosa died on October 23, 1942; Hermann’s life ended on December 17, 1942.

Julius’ sister Hedwig Hirsch, née Löwenstein, and her husband Heinrich were deported from their home in Munich to Theresienstadt on June 25, 1942. Hedwig Hirsch died there on 22.08.1942, Heinrich died on 19.01.1943.

Julius’ brother Wilhelm Löwenstein, who lived in Stuttgart, was deported in August 1942 to Theresienstadt and murdered on March 26, 1943.

His brother-in-law Emil Hilb, coming out of Göppingen, was deported on August 22, 1942 to Theresienstadt, from there to Treblinka on September 29, 1942.

On May 16, 2014 Gunter Demnig installed a Stumbling Stone in memory of Ida and Julius Löwenstein at the location where their former house had stood.

Out of the family Gunz Ida´s grandnephew Andrew Gunz and his wife Barbara came to visit for this occasion all the way from England, taking active part on the ceremony.

(06.02.2017 fw/ir)

Leave a Reply