Spitalstr. 17

In 1876 Elise’s father Michael Wertheimer moved with his parents from the village of Bodersweier near Kehl to Gőppingen. During the same year he married Berta Bauland from Jebenhausen. She also came from family of cattle dealers. After Michael’s death in 1909, his son Berthold continued to run the Wertheimers’ cattle business.

Elise, born on February 17 in 1877 was their first-born child, followed 1878 by brother Berthold and in 1880 by sister Paula, who died young at two months of age.

In the years before her marriage Elise joined the ‘Israelite Young Women’s Association’ and took over the post of vice president from 1895 to 1897. During this time, the Association took on a new task. Dr. Tänzer, Gőppingen’s Rabbi, wrote:

“The highlight of the Association’s work during 1895 was the reorganization of the annual Hannukah celebration by the whole congregation. It had started as a modest celebration for poor children who received presents and were served meals. But soon it was transformed into a much-beloved event for the whole congregation and their young people. Theater performances, speeches, gift raffles etc. were favorites of young and old and garnered appreciation and approval by everyone.”

Unfortunately the documents of these performances only go back to later years, therefore it could not be determined in which way Elise contributed to their content. Most likely her involvement ended on March 8, 1898, because on that date she married Berthold Bensinger, who was 9 years her senior. Like Elise’s family on her father’s side, he also came from Bodersweier and carried on the family tradition as a cattle dealer.

The couple moved to Strassburg, which at that time was part of the German Empire, and resided at Kronenburger Ring, which is now Boulevard du PrésidentWilson. For Elise a whole new world must have opened up in the large city. The first child, son Kurt, was born in 1899, the second son, Max, in 1903. The question of why the family moved to Munich in 1913 could never be answered.

The early death of her husband in March 1916 must have been difficult for Elise. Without any relatives nearby and two teen-age sons she lived alone in Munich as a‘woman of private means’. It must have been a relief for her when her oldest son completed his doctorate at MunichUniversity on February 13, 1923.

The Life Paths of the Sons

Dr. Kurt Bensinger, M.D., soon afterwards moved to Frankfurt/Main, where in July 1925 he married Irma Beatrix Hirsch, née Lange, who was a widow. Irma brought a one-year-old child, her son Otto, into the marriage. It would be six years before little Otto Hirsch’s (step-)brother, a child named Fritz Bensinger, was born. A document (family record book) states that Dr. Bensinger did not work in the profession for which he had studied but as a commercial clerk – years before the Nazi time, it should be noted. Right after the beginning of the Nazi dictatorship the family moved to Paris; their departure date from Frankfurt is recorded as July 6, 1933.

Elise’s younger son Max did not enter university studies and remained in Munich. Several places of residence are recorded for him in Munich, Neu-Ulm and Frankfurt. At first he worked as an apprentice, then as a commercial clerk, and finally as a sales representative dealing in tobacco goods. Like his brother, he left Nazi Germany early and on May 1, 1933, moved to Strassburg, his place of birth, and lived there until the beginning of the war. When the war started, the whole population of Strassburgand ofthe surrounding area was evacuated to the Dordogne, and the Strassburg City Administration moved its offices to Périgueux in southwestern France. Max Bensinger also lived there, at Rue Louis Blanc, and earned his living as a lab assistant and as a sales representative. On February 22, 1940, he married Dora Staripolsky, who was five years older than he and was born in Saverne (Zabern), also out of a Jewish family.

The next and at the same time last mention of Max by the Nazis prior to his murder is anotation on a deportation list which lists the names of people who were taken on November 2, 1943, by the train number 47 from Drancy to Auschwitz.

Hardly any information about the life of Dr. Kurt Bensinger and his family in Francecould be located either. Irma Bensinger must already have died prior to August 1941 in France, because Kurt is listed as a widower in documents that were filled out at a later date. He died as an ‘internee’ in France in 1944 as well.

How did Elise’s grandsons, the two sons of Kurt and Irma Bensinger, survive? Fortunately the names of Bert Fritz Bensinger and Otto Hirsch do not appear on any lists of victims, and at least Bert Fritz must have been able to flee to USA and start a family there.

One can gather from the ‘Memorial Book of Munich Jews’ that Elise Bensinger tried unsuccessfully since November 1938 to arrange her flight to France. The terror of the Pogrom Night must have destroyed any last hope of continuing to live normally in Germany. Because she had no relatives in Munich – might that be the reason why she returned to Gőppingen, the place of her birth, on September 13, 1939?

At first she found a place to live at Spitalstrasse 17. This house belonged to widower Max Hirsch, whose deceased wife Ida, née Bauland, was a sister of Elise’s mother. During the fall of 1939 Elise’s cousins Karl Hirsch and Elsa Hirsch also lived there.

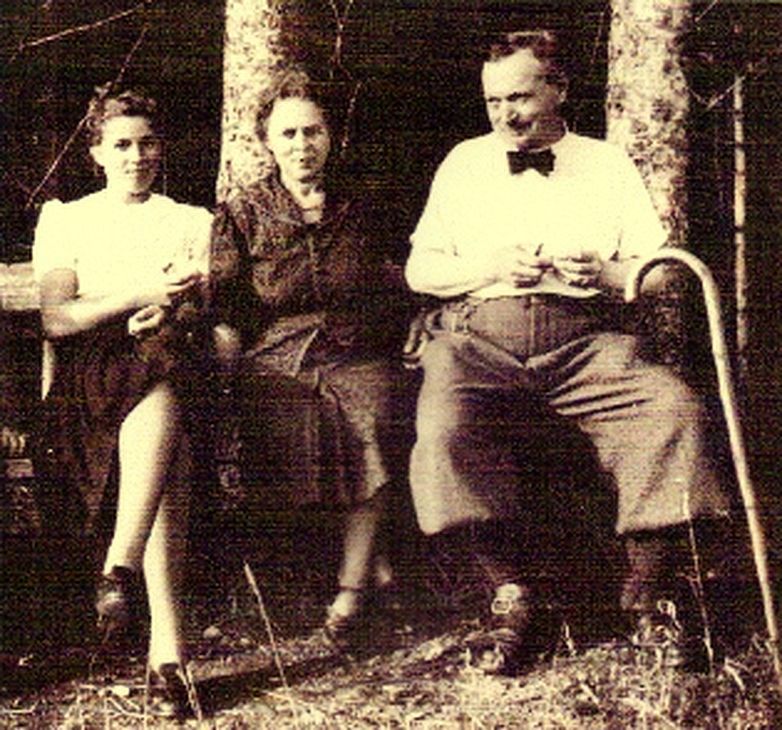

Woman standing in the middle is Elise Bensinger

But it appears that Elise did not live at her uncle’s house the whole time while she was in Gőppingen. The restitution documents for Jenny and Felicia Heimann mention that Elise also lived at the ‘Jewish house’ at Wilhelm-Murr-Strasse 30 (today Mőrikestrasse 30) where she was forced to share a kitchen with several other women.

It appears that Elise must have returned to Max Hirsch’s house because he wrote in his last will and testament on November 5, 1941: “My niece Elise Sara Bensinger, widow, née Wertheimer, in Gőppingen, currently living at Spitalstrasse 17, (…)”.

Incidentally, Max Hirsch wanted to leave half of his property to Elise as an inheritance, the other half should have gone to his sister Helene Simon, because according to Nazi ‘laws’, his children who had fled abroad were disqualified from being named his heirs. On December 1, 1941, at the latest, Elise must have had to leave her residence because on that date the house was sold and the sales contract does not list any stipulation that would have allowed her to remain there.

On August 20, 1942, Elise Bensinger had to leave Gőppingen together with 16 other Jewish men and women and was taken on August 22 from Stuttgart to the ghetto concentration camp of Theresienstadt, where she met her uncle Max Hirsch again. It can be assumed that his early horrible death must have affected her deeply. Even though most of the internees of the group from Gőppingen remained in Theresienstadt for the time being, Elise Bensinger, Pauline Geschmay, Rosa Bűhler and Emil Hilb were transported on September 29 of the same year to the extermination camp of Treblinka. But the date on which they were murdered there is not known.

Other close members of Elise’s family who also died at the hands of the Nazi murderers or due to the horrible living conditions caused by the Nazis are: her sons Max and Kurt, her daughter-in-law Irma, her uncle by marriage Max Hirsch, and her cousins Elsa Hirsch, Paula (Pauline) Mendle, née Hirsch, as well as her cousins Hermann Hirsch, Josef Stern and – probably also – Milton Bauland.

The fate of Elise’s brother Berthold Wertheimer and his family

Berthold Wertheimer lived with his wife Klara, née Fellheimer, at 10 Bleichstrasse in Göppingen, where Berthold was the second generation of the family to run the cattle business. For many years, he was able to run the business at a profit, and his success was reflected in the fact that he owned three motor vehicles. At the beginning of the Nazi era and due to the boycott pressure on his customers, turnover collapsed, so that Berthold Wertheimer had to deregister his livestock business at the end of June 1938. By this time, his son Alfred, born in 1907, had already fled to the USA and was living in Chicago.

During the pogrom night on November 9/10, 1938, Berthold Wertheimer was in a Cannstatt hospital and thus escaped arrest. His daughter Elsbeth Dreyfuss, née Wertheimer, born in 1913, recalled in a letter to Georg Weber in 1966:

“I took the train in the afternoon to visit my father. There were schoolgirls in the same carriage who boasted that they threw eggs and pots at the wall of Café Dettelbacher.” (The Café Dettelbacher near the train station had Jewish owners and was damaged during the pogrom night – author’s note).

Elsbeth Wertheimer was also able to flee to Chicago in 1939.

After the pogrom night, Berthold Wertheimer, like all Jewish Germans, was forced to sell his property for less than it was worth. The family’s house and property were bought by the neighboring Roth company, the motor vehicles were auctioned off and all proceeds were placed in a blocked account. The couple’s escape was dangerously delayed. It was not until the end of August 1941 that Klara and Berthold Wertheimer were able to reach Lisbon/Portugal on a special train that departed from Berlin. This was the only ‘legal’ escape route that remained open until October 1941 due to the hostilities. In Lisbon, the Wertheimers boarded a ship to Cuba, from where they reached their children in the USA. The Wertheimers were therefore the last of the Jewish people from Göppingen who were able to flee. The escape took place as part of the ‘Altreu Passage Procedure’, which the Nazi state paid dearly for. The family lost all their assets in the process.

Elsbeth Dreyfuss writes about the subsequent period:

“I managed to get my parents out of hell in 1941. My mother came with a heart defect and died after 4 months. She was never able to get over the sale of her father’s house, etc., and unfortunately did not live to see restitution. My father was too old to find work in America, and he also died too early (after 1 ½ years) to return to Germany or get a settlement.”

Klara Wertheimer’s cousins Josef

and Theodor Fellheimer and her cousin Elsa Hammer, née Fellheimer,

right: her husband Karl Hammer (Source: Private)

were murdered in the Shoah.

On September 19, 2012, Gunter Demnig laid a memorial stone for Elise Bensinger in front of the house at Spitalstrasse 17, which unfortunately has been torn down in the meantime.

(28.11.2024 kmr/ir/ww)

Leave a Reply