Hauptstr. 20

1996 the Göppingen City Archive office received visitors from Köln. Frida (Fridl) Liebermann showed her son the town where she was born in 1914 as Frida Zitter. They left behind their address in Köln, so the Stumbling Stone Initiative did not have to track down relatives the hard way.

For Frida Liebermann, the return to Göppingen was connected with depressing memories. She and her sister Selma had been able to flee to England in March 1939. However, her older sisters Sara Zitter (born May 1, 1910) and Rosa Zitter (born July 1, 1907) had stayed behind in Göppingen with their widowed mother, Paula Zitter (born February 15, 1881 or 1882). Göppingen, located in Nazi Germany, became a death trap for those in the family who stayed behind.

They were seized and deported to Riga already during the first wave of deportations on November 28, 1941.

‘Jungfernhof’, a former agricultural estate, was used by the Nazis as a camp for approximately one thousand people from Württemberg. The inadequate housing conditions during the winter of 1941 were the main reason for the deaths of many camp inmates, which of course was what the Nazi camp administration had had in mind in the first place. Paula Zitter and her two daughters survived the winter’s intense cold.

In March 1942, the Nazis planned another mass murder. Under the pretext of being taken to another place of work (a canning factory in Dünamünde – which did not even exist) most of the camp inmates were driven into the surrounding woods. German murder commandos (Einsatzgruppen) shot the people in a two-day-long blood orgy. Paula, Rosa and Sara Zitter were among the victims. Richard Fleischer’s letter talks about the transport to Riga and the miserable conditions at Jungfernhof.

Three Decades in Göppingen

28 years prior to the murders in 1942, the Zitter family had moved to Göppingen. There had been several families who made the move because the siblings and their spouses and children all settled there. They came from the Polish city of Lodz which still belonged to Czarist Russia at the time of their departure.

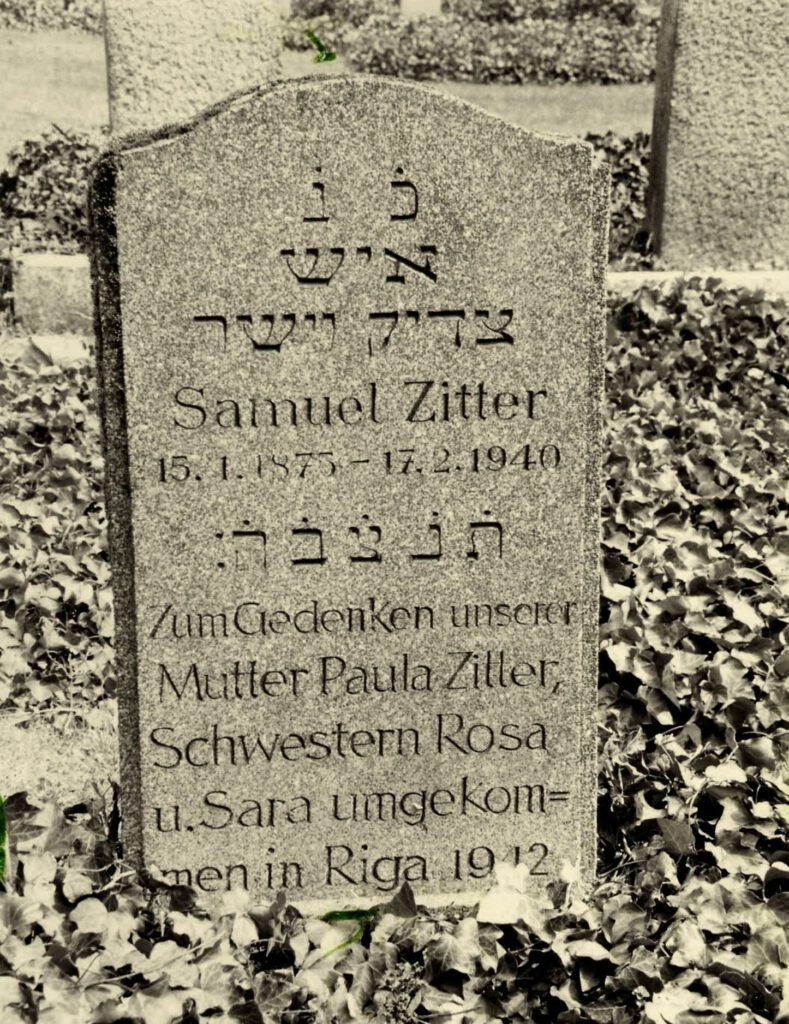

Samuel Zitter (born 1875) was the oldest of the siblings. His wife Paula, née Rottmann, had given birth to their daughters Rosa and Sara in Lodz.

Pinkus Zitter (born 1877), Samuel*s younger brother, and his wife Natalie (Necha), born Rosenberg, already had four sons – Aaron, Hermann, Wolf and Julius.

Ester Kuttner, the youngest of the siblings (born 1882), had by then been married for ten years to Joel Kuttner and brought two sons with her to Germany.

Nothing in the family’s history gives a clue what had convinced them to leave Lodz. However, in the 19th and early 20th centuries millions of Jews left Russia to escape Anti-Semitism and the limited living conditions there.

‘Zitter’ or ‘Cyter’?

Not much is known about the family of Pinkus and Natalie. Natalie, who gave birth to a daughter in Göppingen in 1915, died in December 1922.

On her death certificate, which is signed by registrar Storz, is a notation which was added later on: “Göppingen, October 2, 1935. On orders of the Göppingen district court, the entry was corrected to read ‘Cyter’, not ‘Zitter’.” It is easy to interpret this notation: Jewish people, especially those who came from the East, could not be regarded as Germans, and that should be reflected in their names. It is understandable that a part of the family used the form of spelling ‘Cyter’ ongoing after the war.

Two years after Natalie’s death Pinkus Zitter married Dorothea Bronstein. In 1927 the majority of the family moved to Leizpig.

The Expulsion during the ‘Polenaktion’ [‘Operation Poland’]

Cilly and Julius (Israel Chil) Cyter, a young married couple, remained behind in Göppingen. In October 1938 Pinkus’ youngest son and his wife became victims of the expulsion of Jewish people with Polish citizenship.

In September 1955 Julius writes during the restitution proceedings:

“During the night of October 27 to 28, 1938 my wife and I were awoken by police in our apartment in Göppingen, Haupstraße 11. With drawn revolvers they forced us to come with them and took us to jail. We were only allowed to take our identification papers with us. On the same day (October 28) around noon we were moved under guard to the police station in Göppingen. There we were handed expulsion orders by the Göppingen Landrat [county administrator], dated the same day, and we had to confirm their receipt in writing. We were then taken on a group transport with other detainees to the Stuttgart Gestapo office, and then to the Stuttgart railroad station. Under police guard we were taken in locked railway cars to Bentschen on the Polish border where we were left to our own fate.”

However, this turned out to be a blessing in disguise for Cilly and Julius Cyter. In August 1939 they were able to flee from Poland to Argentina (Buenos Aires). The other children of Pinkus and Natalie Cyter were also able to get to safeness. We are in contact with Michael Cyter, son of Hermann Cyter, as well as with his cousin, Reuven Shachaf, a son of Wolf Abraham Cyter. Both are grandsons of Natalie and Pinkus Zitter.

A Family Achieves Modest Prosperity

We go back to the family of Paula and Samuel Zitter. The Göppingen address books reflect the social advancement of the family: In 1914, Samuel Zitter is listed as a day labourer, living at Vordere Karlstraße 32; in 1924, he is already listed as a weaver, the profession in which he had been trained; and from 1927 on the family lived at Haupstraße 20 in a middle-class residential area.

In the course of the restitution proceedings, Frida Liebermann, née Zitter, drew up a list of their apartment’s furnishings, probably referring to the last apartment at Hauptstraße 20 where the family lived of their own free will: furniture for the living room, the parents’ bedroom, the shared bedroom of the younger sisters Frida and Selma, and separate rooms of the two older sisters.

They probably were an exception among the Jewish families living in Göppingen, because they followed the Jewish religious dietary laws and regulations. According to Frida’s declaration in the restitution documents: “Because we kept a kosher household, we had to have duplicate sets of dishes and silverware. Separate for meat and milk.”

In July 1939 the Nazis forced the family to move to the ‘Jewish houses’ at Geislinger Straße 6 and 8 which belonged to the Dörzbacher family. According to Sara Zitter’s letters, they had to live in very cramped conditions. But she wrote about their landlords as if they were members of their family (“Aunt Gisela”), which would indicate that even though they had been assigned as tenants they had been accepted with kindness.

During their time in Göppingen, all four daughters remained single and were employed.

Rosa worked as a secretary, Sara as a seamstress, and Frida was a sales clerk in the textile store of Julius and Pauline Guggenheim.

Also visible in the picture below left: store sign of the butcher’s store Oppenheimer

Selma and Frida’s Lives in England

Frida and Selma found their life partners only after moving to England. Selma married Martin Goldmann, who had changed his last name to White after he moved to England. Their daughter Susan lives in Canada.

Frida married Emil Liebermann, who had suffered under the Nazi terror in the most horrible way. His son Peter Liebermann reports:

“Originally from Kattowitz, he was educated and worked in Breslau until he was fired from his job there. Together with his [first – kmr] wife, he moved to and settled in Dresden in 1935. Four children were born during this marriage. During the November Pogrom my father was arrested and jailed for quite some time. He had to have emergency surgery on account of the injuries due to the terrible mistreatment he had received, and thus he escaped being transported to Buchenwald. Following the surgery he remained in custody until his release because he had received a visa to go to Shanghai. At the end of 1939 he left Dresden alone. His youngest child was born after his flight. His [first – kmr] wife and children were all murdered.”

Emil and Frida Liebermann lived in England until 1959 and then moved to Cologne where Emil died in 1987. Frida Liebermann died in 2007.

Testimony: Sara Zitter’s Mail Correspondence

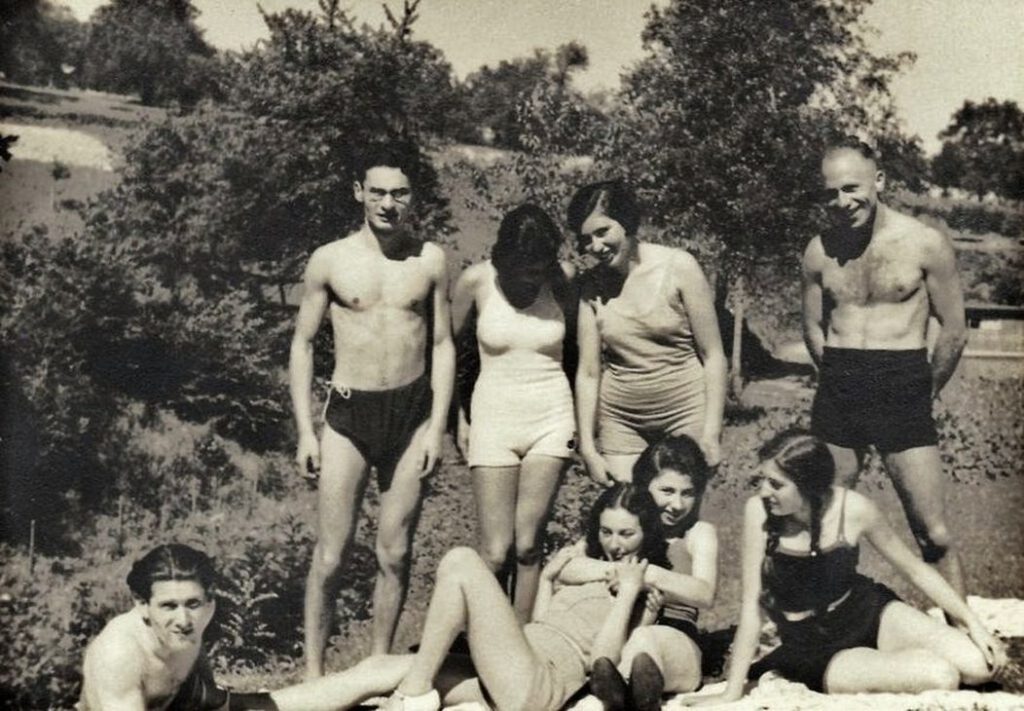

The Stumbling Stone Initiative would like to thank Mr. Liebermann and Mrs. Nau for the many photos they made available that shed light on the life of the Zitter family.

Mr. Liebermann also provided letters which his aunt Sara ‘Susi’ Zitter had written to her sisters in England between August 1939 and August 1941. Since England was considered an ’enemy country’, the letters had to be sent via Switzerland, where their friends, the Neumann family, lived. The letter writer always had to reckon that the Nazi censors would open the letters, and criticism of the living conditions in Germany were therefore not possible. Seemingly innocuous questions about health and eating habits became coded signals because nothing could be taken for granted any longer by a Jewish woman living in Nazi Germany.

Toward the latter part of the correspondence, she expressed general resignation as well as a feeling of helplessness about the common fate of all Jewish people living there at the mercy of the Nazis, and that this was being tolerated by German society in general. The death of their father Samuel Zitter in 1940 took up a large portion in the letters. Even though he had died a ‘natural’ death caused by illness, it takes on a different meaning when viewed against the background of the time. Her veiled remarks hint at a violent death which also threatened her, the letter writer.

Another important subject in Sara’s letters was her job. Even though she was poorly paid and had to travel a long distance to Stuttgart to her job, it gave her a feeling of hope because it offered a confirmation of her value and a distraction from the daily humiliations. But reading between the lines, one can feel her desperation, her hopelessness when the last chance of escape had vanished. Göppingen, the town where Sara and Rosa had grown up, turned its back on them. Neither former school friends nor co-workers and neighbours ever asked any questions about what happened to Sara, Rosa and Paula Zitter on November 28, 1941, or afterwards.

On November 25, 2011, Gunter Demnig installed three Stumbling Stones in front of the house at Hauptstraße 20 in memory of Paula, Rosa and Sara Zitter. Frida Zitter’s son Peter Liebermann and his family attended the ceremony, as did cousins Reuven Shachaf and Michael Cyter who are members of the Pinkus Zitter family, and also Ester Zitter’s grandson Jean-Marie Kutner with family.

(12/04/2017km /ir)

Interview with Frida Liebermann née Zitter

published in:

Unter Vorbehalt – Rückkehr aus der Emigration nach 1945, Cologne 1997, page 163 (excerpt)

“I did not want to go back”

I fought with hands and feet not to go back to Germany. But my husband convinced me, telling me that we should just try it for a year or two. First he commuted between London and Cologne until we decided in 1959 with a heavy heart to move to Cologne. Why did we go there specifically? When my husband took the train to Germany for the first time, his ticket went only as far as Cologne. Then my son enrolled in school, and four years passed very quickly. After that he attended high school (Gymnasium), and we didn’t want to pull him out. In the meantime we tried to find an apartment in London, but that proved to be very, very difficult. I would have gone back if that would have worked out. I kept my British citizenship to this day.”

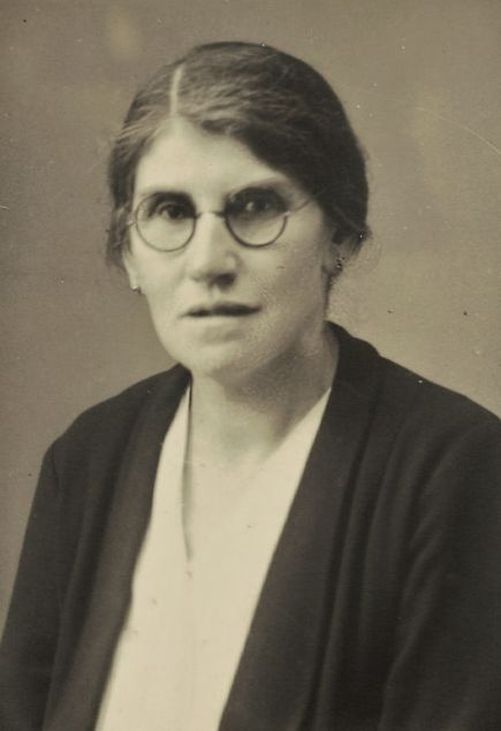

Fridl Liebermann

and her friend Paula Tabak 1996

(Photo: Henning Kaiser/transparent)

Leave a Reply