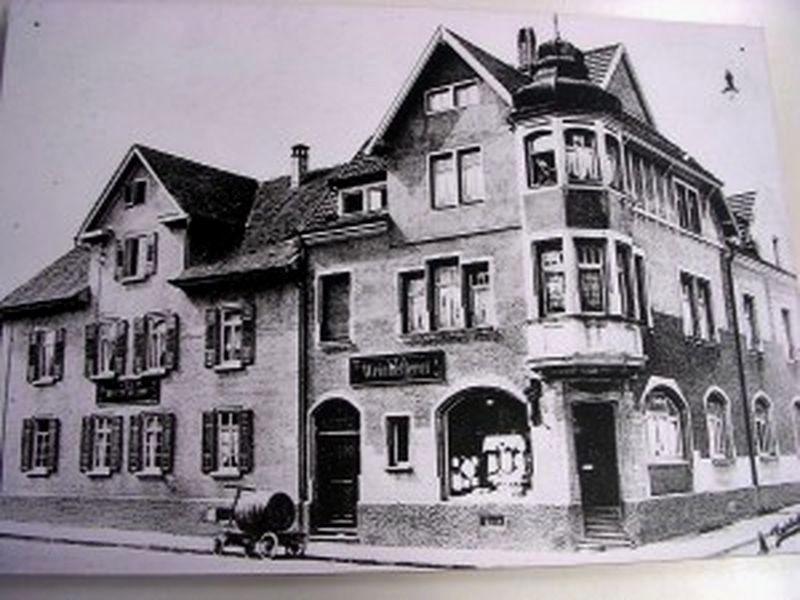

Bahnhofstr. 26

The Heimann family lived on the second floor of the house at Bahnhofstrasse 26. Julius Heimann had rented the spacious five-room apartment with bath from ‘Wine Pflϋger’ – a man who was well-known in the town. His winery and cidery was located behind the residential building which had bay windows. Since 1884, master vintner August Pflϋger had been producing wine there and delivering his delicious beverage to local restaurants. His descendants carried on his business until 1992, when the buildings were torn.

The Heimann family had moved into their apartment in 1929, and witnesses of that time remembered that the Pflϋgers had good relations with their Jewish fellow citizens, especially the Dörzbachers who lived in the house next-to them.

The Julius Heimann Family

Julius Heimann, who was born in 1869 in Göppingen, was first employed as a trained merchant in the women’s clothing store of his father, Adolph Heimann. The business had been founded in 1867 and was one of the best and most well-known of its kind in the city of Göppingen. It was located directly on the Marktplatz [market square] opposite the Rathaus [city hall]. After the death of their father Adolph Heimann in 1903, the sons Julius and Louis took over the management of the fashion- and home furnishing business. A year later Julius married 30-year-old Jenny Sicher, whose parents lived in Munich.

After the death of Jenny’s father, Bernhard Sicher, who had come from America, her mother Nanny, nee Bernheimer, moved in and lived with the family of her son-in-law in Göppingen until her death in 1920. Her grave stone is located in the Jewish section of the Göppingen cemetery.

On November 16, 1906, the daughter of Jenny and Julius, Felicia – or ‘Lici’, as she was known by everyone – was born. She was to be the only child of the Heimanns.

It is not known why Louis Heimann took over as sole manager of their father’s clothing store in 1913, or why Julius Heimann worked independently as the textiles sales representative from then on. It could be possible that the brothers felt that by splitting up their areas of responsibility the business would be more profitable. It can be assumed that this separation of duties was done by mutual agreement because Julius’ daughter Lici did her training in the store of her uncle and then worked there as a saleswoman.

When Julius Heimann moved with his family to Bahnhofstrasse in 1929, he once again listed the residential address the same one as the business address, as he had done previously when they lived at Geislinger Strasse 15. There was enough space for an office in their apartment.

Julius Heimann’s name does not appear in connection with any of the Jewish clubs, but he was listed on the membership list of the ‘Göppingen Liederkranz’ [men’s choir]. Julius gets a special mention in a brochure of 1926, which came out with the celebration of the 100-year anniversary of the choir. He was named as an “Honorary Singer”, because for 25 years he had performed and promoted the treasure of German songs. Thanks to this brochure for the anniversary celebration there is still a photo of him available. All other photos, together with all of the Heimanns’ possessions, were confiscated and destroyed by the Nazis. Julius Heimann had to live for two years under the Nazi dictatorship before dying in a clinic in Tϋbingen on December 8, 1935. His grave is located in the Jewish section of the Göppingen cemetery.

Jenny and Felicia Heimann

Would mother and daughter have left their apartment of their own free will if they had not been forced to do so because of the National Socialist laws? After 1936 they were the only two people who lived in the large 130 square meter [1,400 square feet] apartment, but everything points to the fact that they felt comfortable in their home which was furnished in traditional taste. In the living and dining rooms there were carpets, porcelain and silver flatware was stored the cabinets, paintings decorated the walls, and a Schiedmayer piano was there to play on. The jewelry and clothes of Mrs. Heimann as well as the inheritance – securities, bonds and bank deposits from her husband’s estate suggest that both, mother and daughter were carefully secured. Felicia also worked in her uncle’s textile store and earned money to contribute her share to the household expenses.

The word “voluntary” appears several times in the restitution documents of Jenny and Felicia Heimann in connection with the auctioning of their property. However, it is highly questionable whether it was truly “voluntary” during Nazi times when they had to move into two rooms in a house for Jewish residents in July 1939. The two women had to give up their apartment at Bahnhofstrasse 26. At the beginning on April 30, 1939, all Jewish citizens were forced to move into houses designated specifically for them. ‘Aryan’ landlords who had rented apartments to Jewish citizens had to report this and give immediate notice to their renters. August Pflϋger, the property owner, later made the following official statement during the restitution proceedings: “Mrs. Heimann said that she ‘did not want to cause difficulties because Jews in general were being persecuted’… I would like to emphasize that she was not being pressured by me in any way.

Mother and daughter were assigned two rooms on the ground floor of the house at Wilhelm-Murr-Strasse 1 [today Moerikestrasse 30]. They had to share the kitchen with Mrs. Bensinger and Mrs. Wassermann; both women of the Jewish faith, who had also been forced to move there by the Gestapo [see Stumbling Stones biographies]. Mother and daughter Heimann furnished the rooms with some of their valuable furniture, but they had to release the rest of their household goods to be auctioned. Jewish property could be bought at bargain prices. In the proceedings of 1960 the question (once again) was brought up if the auction had been carried out forcibly or that if the Heimanns, Jenny and Felicia, auctioned “voluntarily.” An answer according to the documents recording the proceedings “could not be determined from the document’s listings”… but the history and actions of the Nazis prove that it was their goal to bereave the Jews.

Felicia lost her job in her uncle’s store because Louis Heimann was forced to sell his clothing store in the course of the ‘Entjudung’ [elimination of Jewish persons out of the economic system]. Instead Felicia was forced to take a job as a seamstress with the Fϋrstenberg Company, which was owned by the Block brothers until 1938 when they too could no longer resist the destructive methods of the Nazis and had to sell their company.

We can thank a contemporary witness from Donzdorf who was by then a 16-year-old apprentice, that the seven or eight slave laborers were not forgotten. These women had been forced to sew bedding etc. for the Fϋrstenberg Company in an adjacent farm house at Bartenbacher-Strasse. It was his job to supply the women with the cloth materials. He could especially remember a Mrs. Heimann, having striking large eyes, pale face, ‘almost crystallite’, she was a slender and tall person, approximately 40 years of age, he remembered. He felt sorry for her and in spite of the fear of punishment he gave her a piece of bread from his lunch once in a while hiding it between the pieces of fabric. He remembered Felicia Heimann for the rest of his life, the aged man declared; he could note the thankfulness in her eyes. After 70 years there was nobody besides him in Göppingen who could remember her or her mother Jenny.

Deportation and Murder of the Two Women

On November 27, 1941, the first deportations from Göppingen took place. 39 Jewish men, women and children had to spend their last night in the gymnasium of the Schiller School. The next morning they were taken to the railroad station by officers of the criminal- and security police. For Jenny Heimann this was her last opportunity to see her daughter, because Felicia was one among this first group of deportees. After a short stay at the transit camp at Stuttgart-Killesberg the group left on December 1, 1941, on the first deportation train from Stuttgart’s Northern Railroad Station. The destination was the city of Riga in Latvia.

Only one deportee from Göppingen survived: Richard Fleischer, a then-14-year-old boy, who wrote a letter to his father after his liberation from the concentration camp in 1945. In this letter he described the transport to Riga as follows:

“At 4:00 a.m. we were loaded onto train cars at the Northern Railroad Station and were forced to ride for three days and four nights in unheated wagons to Riga. We only received water twice along the way. We were half dead from thirst when we arrived. We were unloaded like cattle, being hit with sticks and screamed at. Many people slipped and fell on the ice and were shot. Twenty-eight people died in ten minutes. We got the correct impression right away. We ate ice and snow because we were so thirsty and were driven into some old barns and sheep stables, and there we had to remain in the ice and snow until the end of March. Every day between 18 and 25 men died in our barracks, they froze to death during the night. Many also died of typhus, dysentery, and frostbite.” [for the complete text of the letter: see the appendix to the Stumbling Stones biographies of Irma and Julius Fleischer].

Did 35-year-old Felicia Heimann survive this inferno? Just like Richard Fleischer, she arrived in Latvia on December 3, 1941. The plan had been for deportees to be taken to the Riga Ghetto. But because of the complete overcrowding of the houses of former Latvian Jews in the ghetto, the deportees from Württemberg were taken to the Jungfernhof estate near Riga. Most of the buildings on the premises were dilapidated, unheated, and totally inadequate for housing 4,000 people – additional transports from other places also arrived there.

Starting in March 1942, the so-called ‘Action Cannery Dϋnamϋnde’ took place. To start with, about 1900 ‘Reichsjuden’ [Jewish citizens who lived in the Deutsche Reich] were selected from the Riga Ghetto and shot. Then, on March 26, the ‘Action’ targeted the people who had been housed at Riga’s Jungfernhof as well. Under the pretense that they were being moved to a new camp where they would have the opportunity to work at a cannery under better conditions, the camp commandant had 1600 to 1700 inmates loaded onto trucks and transported to nearby woods. There they were murdered in cold blood by the Nazis and buried in hastily dug holes. Only 43 of the 1013 people who had been deported from Stuttgart survived.

Nobody knows on which day Felicia Heimann died, nobody knows with certainty if she was murdered there or if her last resting place is in a mass grave in the Forest of Bikernieki near Riga.

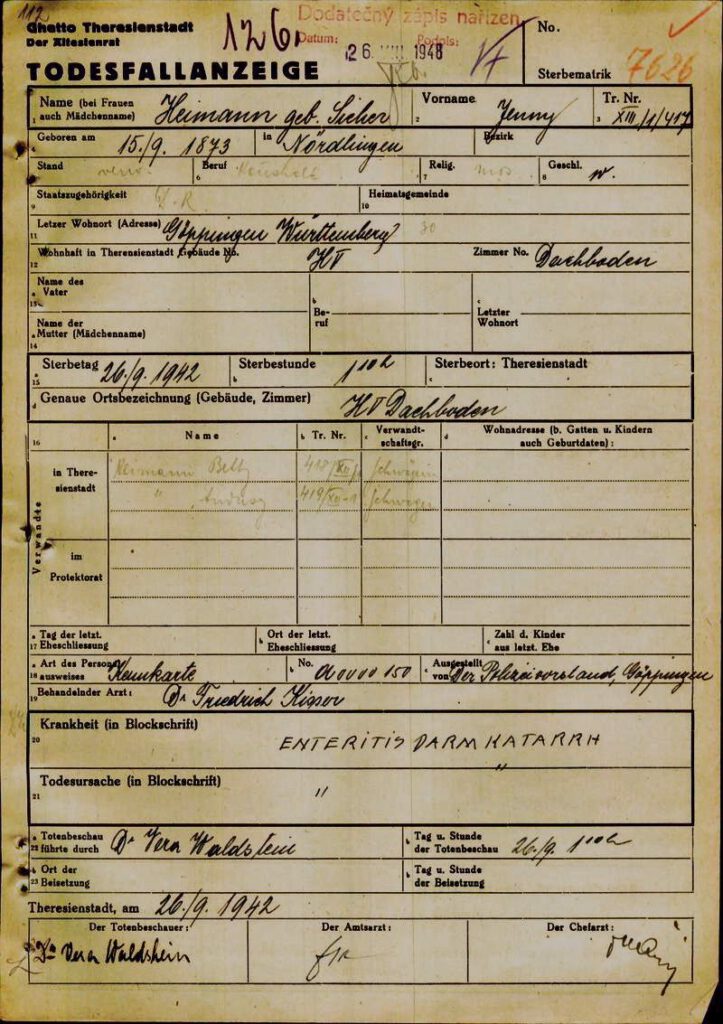

Did her mother Jenny ever learn of the horrible life circumstances which led to her daughter’s death? She herself was deported in August 1942. At that time, 23 people, mainly older Jewish men and women from Göppingen, became the victims of the Nazis’ murderous madness who planned to make Germany and the occupied territories ‘judenfrei’ [free of Jews]. Jenny Heimann together with her brother-in-law Louis Heimann and his wife Betty was taken to Theresienstadt concentration camp near Prague.

She died there on September 26, 1942, one month after her arrival – due to murderous living conditions.

On November 25, 2011, Gunter Demnig laid Stumbling Stones in memory of Felicia and Jenny Heimann.

(09/01/ 2017 clm / ir)

Leave a Reply