Frühlingstr. 29

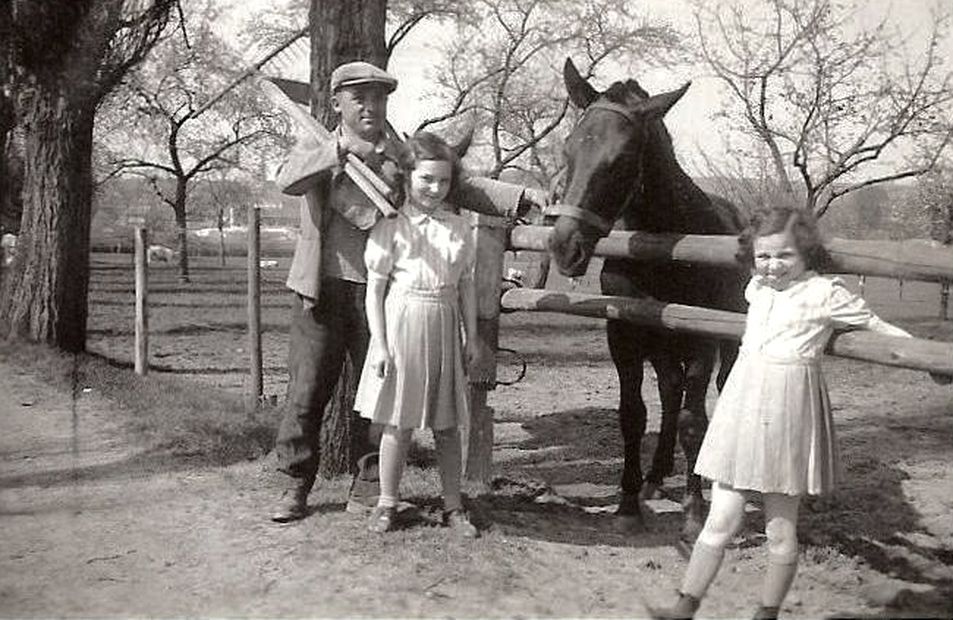

One could actually enjoy this photo of the friendly Opa (grandfather), the small girl who smiles into the camera while holding the baby, her stepbrother, on her lap. But it is the year 1939, and the family knows that there is no future for them in Germany. The father of the family, Ludwig Oberdorfer, was already in Dachau concentration camp; the factory equipment of the family business had to be sold to a NSDAP – Ortsgruppenleiter [local group leader], and many friends and acquaintances had already fled abroad. The Oberdorfer family planned to immigrate to the USA too. Their most important belongings had already been packed into a container, eight suitcases and six boxes in Rotterdam or Genoa; RM 5,676 had to be paid for transfer fees. But they still hoped to be able to escape the harassment and humiliations of Nazi Germany.

We do not know who took the photo, if it was the father, the mother, a relative or a friend. It was found by Beate Dőrzbacher, a fellow student of the girl in the picture. Today her name is Betty Greenberg; she lives in the USA and also sent us other photos of the Rődelsheimer girls. However, it was not possible to locate other photos or personal documents of the Hilb-Rödelsheimer-Oberdorfer family.

The people in this photo are the grandfather, Emil Hilb, the grandchildren, Lise and Doris Rődelsheimer and their small stepbrother Franz-Sepp Oberdorfer. We do not know the faces of the parents (Elsbeth and Ludwig Oberdorfer). There is not a single memento which could give us any hint of their personalities.

Emil Hilb is the first and only member of the many branches of the Hilb family who became a resident of Göppingen. Born in Baisingen on November 28, 1864 as son of Joseph Hilb and Fanny née Kiefe, he was the seventh out of 13 children. Both of his parents came from Haigerloch, his father was a horse trader. Of the Hilb and Kiefe families One can find many graves in the beautiful Jewish cemeteries of Baisingen and Haigerloch. A brother of Emil, Siegfried Hilb (born January 28, 1871 in Baisingen, died April 4, 1932 in Konstanz), was the father of Ernst Hilb (born July 20, 1904). For many years, Ernst represented the Göppingen Hilb family regarding their inheritance in the restitution negotiations. The correspondence regarding these negotiations is located in the State Archive in Ludwigsburg and was used as the primary source for the details of the family biography compiled here.

We do not know anything about the childhood of Emil Hilb. We can imagine that he was an ambitious boy who had training in merchandise. From 1890 to 1895 he was registered as a merchant in Heidelberg, and at one time he is listed as co-owner of the firm Baer & Hilb, Karlstraße. 2. On November 10, 1891, he married Selma Lőwenstein (born September 2, 1869, out of Göppingen) in Göppingen. After their wedding, the couple most likely continued to live in Heidelberg. At any rate it is reported that Emil Hilb at the age of thirty moved from Heidelberg to Göppingen and founded the Emil Hilb Company which manufactures fabrics for mattresses, beds and upholstered furniture. It is mentioned somewhere else in the document that after the death of Max Werthauer in 1912, who was the sole owner of the Firm Jakobsohn and Werthauer, Emil Hilb took over the company and liquidated it in 1925.

The first child of the Hilb´s was born in Göppingen in 1899, a girl named Marie who only lived for one day.

Elsbeth Johanna was born on September 2, 1900, the birthday of her mother too.

Once again, nothing is known about the childhood of Elsbeth. Although she probably did not receive job training, we can assume that she became an active, involved woman who got to be a working co-owner in her father’s business. In a report by the Israelite Youth Club of 1923 she is listed as secretary. This club had been founded on March 20, 1920 after a meeting of the congregation. It was at the height of its development in 1923, with 53 active and 44 supporting members.

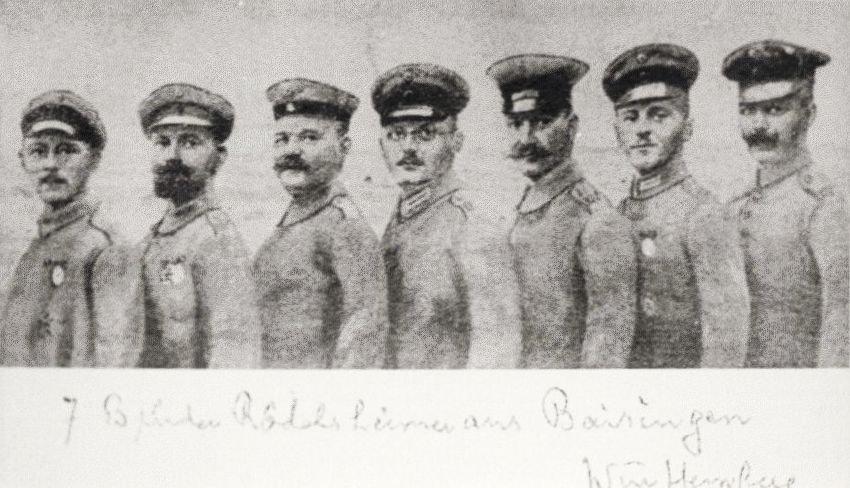

On May 15, 1922, Elsbeth married the merchant Heinrich Rődelsheimer out of Baisingen, who was ten years older than she. We also know very little about him. There is a photo of him and his six brothers, most likely taken in times of World War I. They are all wearing uniforms. But which one of them is Heinrich? On January 1, 1924, Heinrich became co-owner of the Emil Hilb Company, which was converted into an “oHG” [partnership].

During the year 1924, their first child, Lotte Sofie, is born, but she only lives to the age of three. Lise is born as second child on August 31, 1928, and Doris on August 18, 1930. In 1932, Heinrich Rődelsheimer died in a Catholic hospital in Stuttgart (most likely Marienhospital). There are some photos from the time after with his two daughters, one with their ‘Opa,’ (grandfather) another with a horse and groom. One could imagine that they lived in comfortable circumstances and had a loving family home.

No memories of Doris and Lise’s childhood and school days have been handed down. It is certain that they attended the elementary school for Jewish children which had been established in 1936. Children of different age levels were instructed by a young teacher named Fritz Max Erlanger and later by Rabbi Luitpold Wallach. Probably they had similar experiences as Herbert Steiner, a fellow student living in the USA, who described his experiences on his walk to and from school in an e-mail of April 13, 2011: “The direct route from the Bahnhofstraße was not very far, but the detours I had to take to avoid the rock-throwing of other school boys made it a serious undertaking.”

In the meantime Emil’s wife Selma, née Lőwenstein, died on September 14, 1936 at the age of 67. They were married for 45 years. Until now we unfortunately were not able to find any traces about Selma’s life.

On July 19, 1937, five years after her first husband Heinrich Rődelsheimer had passed away, Elsbeth married the merchant Ludwig Oberdorfer.

Ludwig Oberdorfer was born on March 15, 1893 in Regensburg. His parents were Samuel Oberdorfer and Ricka née Rosenblatt. It is known that he was an officer during World War I. Ludwig must have had an higher education, because otherwise he would not have been able to become an officer – as was concluded by Eugen Zeller, who later purchased the factory equipment of the Hilb Company. In his civilian occupation Ludwig was a merchant. In the years after the war he was registered in several cities, including Munich, Darmstadt and Düsseldorf. On August 27, 1937, he became part-owner of his father-in-law’s company, the Emil Hilb “oHG” [partnership]. A year later, on September 1, 1938, Emil Hilb left the company.

But prior to that, a joyous event took place in the Oberdorfer family – the birth of their son Franz-Sepp.

On November 9, 1938 there were immediate consequences for Ludwig Oberdorfer when the signal for action against Jews and Jewish businesses was given and the Synagogue in Göppingen was burned down by SA-men. During that night, 40 Jewish men between the ages of 17 and 72 were forcibly taken from their homes. 27 of them, whose names and addresses were collected beforehand, had been transported to Dachau concentration camp two days later.

Justin Heumann, who survived, wrote 1966 in a letter from his new home in Caracas about the indescribable conditions in the camp and the treatment of the inmates. He reports for example that the inmates were coerced into selling their property with the option to shorten their stay in the concentration camp. Ludwig Oberdorfer was at the Dachau concentration camp from November 11 to November 26, 1938. On December 27, 1938 he was forced to sell his factory equipment to NSDAP-Ortsgruppenleiter Hermann Finkbeiner, who re-sold it to Eugen Zeller on February 18, 1939.

The actions against the Jews did not cause a storm of protest, but there was some disapproval in the remaining non-Jewish German citizens. On December 28, 1938 there was a membership meeting of the NSDAP. The already mentioned Ortsgruppenleiter Finkbeiner reacted to comments of disapproval with the demand “that these incorrigible complainers should be expelled from the Arian community…” and appealed, “the solution of the Jewish question should be a cause of joy for every decent person. Whoever feels pity for the Jews cannot be a German. If something is taken away from the Jews today it is only a small portion of what they already have amassed through crooked means. The accusation of ungodliness is not justified here.”

During the following months, the Hilb-Rődelsheimer-Oberdorfer family prepared for their emigration to the USA. Their destination was New York, where a cousin of Elsbeth Oberdorfer had guaranteed the support for the family. Siegfried Mayer, the son of David Mayer and Ida née Hilb had a shop selling shirts and ties in New York City. Their movable possessions had first been stored in Rotterdam and later in Genoa. The transport costs were larger than RM 5,676, much more than the annual salary of Ludwig Oberdorfer, who earned RM 400 per month. The family had a hard time with obtaining required papers. They were under constant harassment and humiliation.

Ludwig Oberdorfer wrote in letters to Ernst Hilb, a cousin of his wife Elsbeth, who stayed in Switzerland, about the misery they had to endure (text attached below).

On May 10, 1939 family Oberdorfer / Rödelsheimer had to move out of their apartment which was part of the factory at Schützenstraße 8. They found shelter at Frühlingsstraße 29, a house that belonged to the Jewish family Veit. Emil Hilb, who had lived at Poststraße 6 later moved to this house too. The distress increased constantly, so everybody searched desperately to find a refuge for relatives. Friends themselves were not in a position to help either. (e.g. Family Oberdorfer wanted refuge for family members and hoped for open doors at the Frankfurter family, but they were not able to help, the house was already overcrowded.) This put a lot of pressure on friendships. A friend of the family, Hedwig Frankfurter, wrote on September 3, 1941 to Mathilde Gutmann in Zürich:

“Dear Thilde, it´s so sweet and thoughtful of you to think of our most needy. There is much misery and by contrast there is not much help… and what I didn’t know and what troubled me most is Els Oberdorfer. In all the misfortune poverty is added.”

The next blow was a ban on emigration for Jews which was issued by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt [State security main office] under Heinrich Himmler on October 23, 1941. This shattered all hope to escape the Nazi terror. During the prior months there already had been a change in the policies regarding the Jews: the goal was now no longer their expulsion, but the annihilation of the Jews.

The first transport, which had been disguised as a relocation of those affected, involved the Oberdorfer / Rödelsheimer family, including the three children.

On November 20, 1941, Hedwig Frankfurter wrote to her son Richard Frankfurter:

“We are completely demoralized. Within a week, the community will be diminished approximately by half & there is understandable panic. The whole Oberdorfer family will be included. My hope is now that at least we will be able to shake hands before a permanent farewell. It shouldn’t be my fault.”

And on November 26, 1939:

“We live during a very sad time. Tomorrow good friends and acquaintances will be leaving us, such as the Oberdorfers, the Banemanns, the Jul. Fleischers, our former maid Rosel & mother, I said good-bye to Els yesterday; in view of their difficult fate, I forgave her for what have happened in the past.”

On November 27, 1941, the Oberdorfer family had to turn themselves in at the Göppingen Schillerschule, where they had to submit to a body search. The next day, after they had to spend the night with approximately 34 other people in the school’s gymnasium, they were taken to Stuttgart to the Killesberg. A transit camp for 1,000 persons had been set up there for the purpose of organizing a transport to the “Reichskommissariat Ostland” (German occupied Baltic parts of Soviet Union), meaning Riga. Richard Fleischer, who was 14 years old at the time, was the only one of the Göppingen Jews to survive this deportation. In a letter to his cousin Erwin Fleischer he wrote:

“At 4:00 a.m. we were loaded onto railroad cars at the Northern railroad station and transported for three days and four nights in unheated cars to Riga. Along the way, we were given water only twice and were nearly dying of thirst. When we were unloaded, we were treated like cattle with beatings and screaming. Many people fell on the glare ice and stayed behind and were shot. Within ten minutes, there were 28 deaths. We knew right away where we were standing. We ate ice and snow because we were so thirsty. We were herded into some old barns and sheep stables. In our barracks, 18 to 25 men died every day because they froze during the night. Many also died of typhus, dysentery, and frostbite.” (Complete text follows the Stumbling Stone biography of Irma and Julius Fleischer).

In a notation on a document of October 5, 1967 about the settlement with Elsbeth Oberdorfer’s heirs in regards to loss of freedom, Dr. Hartlieb wrote the following:

“From experiences and statements that have been collected about the fates of the Jews who were deported to Riga and were missing there, it can be assumed with the strongest probability that all family members were immediately annihilated. It involves a family with three children, of whom the oldest was 13 years old, and the youngest 3 ½. In such cases it must be assumed that in all probability the parents who did not want to be separated from their children lost their lives on March 27, 1942, in the `Großaktion Dünamünder Konservenfabrik´ and did not survive.”

It is difficult to assess what these first deportations must have meant for those who were left behind. One can feel the deep anxiety in the letters of Hedwig Frankfurter. Several times she mentions the father and grandfather of the Emil Hilb family stayed behind. On December 3, 1941, she writes to Richard Frankfurter:

“Mr. Hilb visits us often and is very distraught.”

On December 28, 1941, she writes to Mathilde Gutmann:

”Mr. Hilb feels very lonely and hopes to be taken into an old-age home.

On January 29, 1942, to Mathilde Gutmann again:

“Mr. Hilb has been taken to the old-age home in Laupheim, and because of this, his sad loneliness has been alleviated somewhat.”

However, the move to the Jewish old-age home was not a voluntary decision, but a compulsory act and had nothing to do with humanitarian considerations but served solely as interim housing before annihilation.

In 1939 the “State Association of Jews in Germany” had converted the former Rabbinical building at Synagogenweg in Laupheim into an old-age home. Not only older people from Laupheim, but also Jews from other cities were housed there under extremely cramped conditions.

On August 19, 1942 the deportation of 43 old people took place, among them Emil Hilb. They were taken from Laupheim to a transit camp at Stuttgart’s Killesberg, and on August 22 from there on to Theresienstadt. On their arrival, the total number of inmates there had risen to 52,554. On September 29 the transport to Treblinka extermination camp took place which ended for Mr. Hilb with execution.

Other members of the Hilb / Löwenstein / Oberdorfer / Rődelsheimer families were also murdered in German camps.

Bertha Lauchheimer, née Hilb, a sister of Emil Hilb, died on February 10, 1943, in Theresienstadt.

(Source: The Biographical Memorial Book of Munich Jews 1933-1945)

Hedwig Hirsch, née Lőwenstein, sister of Emil Hilb’s deceased wife Selma. She died in Theresienstadt on August 22, 1942, her husband Heinrich on January 19, 1943.

Wilhelm Löwenstein, Emil Hilb´s brother-in-law out of Stuttgart was murdered in Theresienstadt on March 26, 1943.

Ricka Oberdorfer, the mother of Ludwig Oberdorfer out of Regensburg was murdered on February 1, 1944 in Theresienstadt.

Three brothers of Heinrich Rődelsheimer, the first husband of Elsbeth Oberdorfer, née Hilb, and a sister-in-law:

Max Rődelsheimer out of Pforzheim was deported on August 10, 1942 to Auschwitz and murdered.

Wilhelm Rődelsheimer out of Neunkirchen was murdered on July 12, 1942 in Auschwitz.

Siegfried Rődelsheimer out of Pforzheim too, was murdered on December 18, 1938 in Buchenwald.

Lina Rődelsheimer, née Fleischmann out of Neustadt an der Weinstraße, widow of Hugo Rödelsheimer, lost her life on December 6, 1940 in Gurs / France.

On September 19, 2012, Gunter Demnig placed Stumbling Stones in front of the house at Frühlingsstraße 29 for Emil Hilb, Elsbeth, Franz-Sepp and Ludwig Oberdorfer, as well as for Lise and Doris Rődelsheimer.

We are very grateful to Betty Greenberg forwarding the photos of the family Hilb / Rödelsheimer / Oberdorfer to us, as well as lots of thanks to Mr. Tobias Engelsing for the permission to use parts of his book for quotes (“Das Jüdische Konstanz”), see attached.

(11.04.2013/14.01.2017 fw / ir)

Excerpt from: Tobias Engelsing, Jewish Konstanz

Page 155ff: Rejected for “Reasons Due to Foreign Influences” (???): The long struggle to the Hilb family to find a new home.

A bundle of letters carefully kept in the family archive reveals a special accomplishment by the young man fighting persistently for his future. He was faced with serious difficulties himself, having to leave his hometown and worrying about continuing to be “tolerated” in Switzerland. Despite all of his own worries Ernst Hilb tried to help his family members who were in much greater danger than he: Living in Gőppingen, his uncle Emil Hilb as well as his daughter Elsbeth and her second husband Ludwig Oberdorfer with their daughters Lise and Doris and son Franzl who was born in 1938 (Datum?). Ludwig Oberdorfer was a shareholder and eventually owner of his father-in-law’s company which manufactured fillings for mattresses, upholstered furniture and beds. After the pogrom in November 1938 Ludwig Oberdorfer was imprisoned in Dachau concentration camp with other Jewish men from Gőppingen. Upon his return he was forced to sell his company at an unfair low price to the local Nazi group leader. After that time the correspondence between the Gőppingen Hilb-Oberdorfers and the Kreuzlingen Hilbs intensified.

Ernst tried to find emigration opportunities and cope with consulates, travel agencies, shipping companies, as well as often shady emigration agents. While doing all this he used resources available in Switzerland to find a way for his Gőppingen relatives to emigrate to a safe third country. Inquiries to Chile, Bolivia, Brazil, Cuba, Venezuela, Nicaragua, South Africa, Argentina, Haiti, Peru and the Dominican Republic were channeled through his address. Since Jews were no longer allowed to have telephones in the German Reich, and since long-distance calls were much too expensive for his relatives who were now in serious financial difficulties, Ernst maintained a frequent mail correspondence with Ludwig, his cousin by marriage. In the beginning Ludwig, a native of Regensburg, tried to keep a cheerful tone in his letters and to sound optimistic and confident in his hope that a country somewhere in the world would eventually accept him and his family: “And when the time is right, we will have to put our heads together and try everything, even if it means traveling on a cargo steamer,” he wrote in the summer of 1939. But then Ernst Hilb became ill and needed an operation, and he warned Ludwig that a decision would have to be made quickly because Santa Domingo, Chile and Cuba were still open. However, Ludwig hesitated because at that time he was considering Haiti.

Just then, the war began and many countries closed their borders. Ludwig’s letters soon sounded hopeless, his family was terribly afraid. At the beginning of 1940 he found out that it was now a requirement that $5,000 in U.S. currency had to be deposited as a guarantee to be accepted in Haiti. Ludwig Oberdorfer’s monthly salary that he now earned at his own firm amounted to only RM400. Oberdorfer asked in his letters if anyone else besides his American cousin who was sponsoring the family for immigration could assist Ernst Hilb in obtaining the necessary immigration permits, raise funds and somehow get them to safety. A cousin in New York, the owner of a necktie store, had already made a considerable deposit. These funds now appeared to have been lost because of unscrupulous agents and political developments.

In March 1940 Ludwig Oberdorfer wrote the following bitter lines about the beautiful but remote idea of a reunion with Ernst:

“But because everything is at point zero except our USA-number, those prospects are more than just bad. Please let us hear from you soon; we anxiously await every letter and hope and hope and hope.”

In addition to the uncertain prospects for emigration, there were now also financial concerns because Ludwig Oberdorfer no longer had any income. More and more frequently Ernst announced in his letters that once again food items were being sent: Swiss chocolate, cheese and Ovaltine were enjoyed by his relatives. In December 1940 Ernst Hilb reported cautiously that the Jews from Baden had just been deported to Camp Gurs: “You probably have heard that many of our former acquaintances have been taken to southern France. They are in need of good warm clothing, boots, pillows, etc.” Would the Gőppingers who already were in dire straights themselves still have been able to assist their family members in Gurs? The letters say nothing about it.

In December 1940 the hopes for going to the United States sank once again: “We are extremely depressed,” wrote Ludwig to cousin Ernst. Several months later, when the attack on the Soviet Union had just begun, the American consulate in Stuttgart closed its doors. This was particularly bitter news because the Oberdorfers’ visas had been approved at the last minute, only the arrangements for ship passage still needed to be made. “I really don’t know what to do any more, can you advise me?” Ludwig asked the relatives in Kreuzlingen in June 1941. Once more there was some hope after Ernst Hilb resumed his attempts to help. But now it would be necessary to raise US$ 2,000 for the ship passage tickets – which was more than it had been before. Another relative in the USA had donated half of that amount. “We would be happy to travel in a third-class cabin on the ship,” Ludwig assured his cousin Ernst, but the relatives in Kreuzlingen were not able to raise the rest of the money.

When things still had not progressed any further by September, Ludwig wrote: “As you can easily imagine, we are mentally totally exhausted, and I can no longer hope to make emigration a reality.”

His last lengthy hand-written letter is dated October 17, 1941. It gives shocking testimony to their hopelessness and feelings of being lost. Ludwig Oberdorfer sums it up bitterly: “Our emigration failed because of our own helplessness.” Cuba and Chile, the last hopes for salvation suggested by Ernst Hilb, were unreachable due to lack of money. Ludwig’s last lines to his relatives who had tried so hard to help were: “So we must always hope and wish that soon there will be peace again and that the Lord will have pity on us.”

Six days later Reichfűhrer Heinrich Himmler issued a general ban on Jewish emigration. The policy of the Nazi regime regarding the Jews now started its most radical phase, the extermination of Jewish life in Germany and the occupied territories. On November 27, 1941, the first Jewish citizens of Gőppingen were deported, carrying only small luggage, via Stuttgart to the “Reichskommissariat Ost”, the Riga ghetto. Among them were Ludwig and Elsbeth Oberdorfer and their children Lise, Doris, and three-year-old Franzl. Elsbeth’s father Emil Hilb remained behind by himself in Gőppingen for now.

“Mr. Hilb visits us frequently, he seems quite distraught,” reported an acquaintance after the deportation of the Oberdorfer family. In December Emil Hilb wrote to the Kreuzlingen relatives himself in the hope that they might be able to give him some news on the whereabouts of his family. But there were no news. In the following summer, Emil Hilb was deported to Theresienstadt concentration camp and from there to Treblinka extermination camp where he was murdered. The Hilbs in Kreuzlingen were able to give some last assistance to Ricka, Ludwig Oberdorfer’s mother. She also had been deported to Theresienstadt. At least she was allowed to write to Kreuzlingen and once in a while receive a food package from there. On her last postcard to the Hilbs, written on October 13, 1943, in Theresienstadt, she thanked them for their greetings and wrote:

“It worries me greatly that neither you nor I have heard anything from Ludwig, but I hope good news will soon arrive through the Red Cross.”

This hope would not be fulfilled. According to later findings, the whole Oberdorfer family lost their lives in a massacre in March 943. Ricka Oberdorfer died at Theresienstadt concentration camp in January 1944.

Leave a Reply