Born on 22.01.1872 in Laurahütte (Polish: Huta Laura)

Deported to the Treblinka extermination camp on 26.09.1942 and murdered there

Interned in Weißenstein in February 1942

Berta Boss, née Heimann was born into a Jewish family in what was then Upper Silesia . Her parents were Emma, née Cohn and the forwarding agent Wilhelm Heimann. Berta had at least two siblings. The Heimann family lived in Siemianovitz, the neighboring village of Laurahütte. It is not known whether Berta received professional training as a young woman; after her marriage she worked with her husband as a businesswoman.

Berta moved to Stuttgart before 1900, when exactly and from where could not be clarified. At the beginning of July 1900, she then moved to Munich, where she worked as a ‘Ladnerin’. In Munich she probably met her future husband, the merchant Josef Boss, who had been living in that city since September 1900. However, the couple wanted to start a future together in Offenburg / Baden, where Josef was registered from October 1902.

Josef Boss also came from Upper Silesia, he was born on August 21, 1868 in Zülz (Polish: Biala) as the son of Ernestine, née Breslauer and Adolf Boss. His birthplace Zülz was part of a regionally radiating Jewish tradition.

Berta and Josef’s wedding took place on February 24, 1903 in Strasbourg / Alsace, where Josef Boss’ brother, Dr. Siegfried Boss lived and practiced medicine. Their three children were then born in Offenburg: Adolf on March 22, 1903, Edith on November 16, 1904, and Erwin on February 12, 1906.

On May 31, 1910, the family moved to Villingen, where Berta and Josef opened a ladies’ and girls’ clothing store at Obere Str. 1. Heinrich Schidelko of the association ‘Pro Stolpersteine Villingen-Schwenningen’ has determined the following about the Boss department store:

“It was with its 8 – 10 employees one of the large department stores in the city, which attracted attention in the daily newspaper of the time, the Villinger Volksblatt, at the end of the twenties with very large advertisements or special campaigns. For example, on a Saturday or Sunday from 3 to 6 p.m., the citizens of Villingen were invited to a spring concert from the historic bay window. A brass band played upstairs and the windows were opened for this purpose – downstairs the citizens listened. There was also at least once an open Sunday at the Boss department store, as could be read in the Villinger Volksblatt.”

Even though Berta was now ‘at home’ in southern Germany, she must still have had a connection to the region of her birth. When in the spring of 1921 a referendum was called on the national status of Upper Silesian territories, she traveled to her native town as one of five citizens from Villingen in order to be able to participate in the vote on the spot. It may be assumed that she voted for the region to remain in the German Reich.

Berta and Josef Boss were considered by business partners and neighbors to be capable and personally modest businessmen. However, the economic crisis at the end of the 1920s / beginning of the 1930s put a strain on their business, which was initially doing well. In addition, loans for the remodeling of the business building, which had taken place in the second half of the 1920s, had to be paid off.

The 1930s initially brought good news for Berta: Her eldest son Adolf had successfully completed his medical studies in Freiburg and worked as a doctor at the Virchow Hospital in Berlin. Here he married in 1930 Josefine Stapenhorst, a fashion designer three years his junior, who came from a non-Jewish Protestant family. And on October 28, 1932, Berta’s first grandchild was born: Valentin Josef Boss.

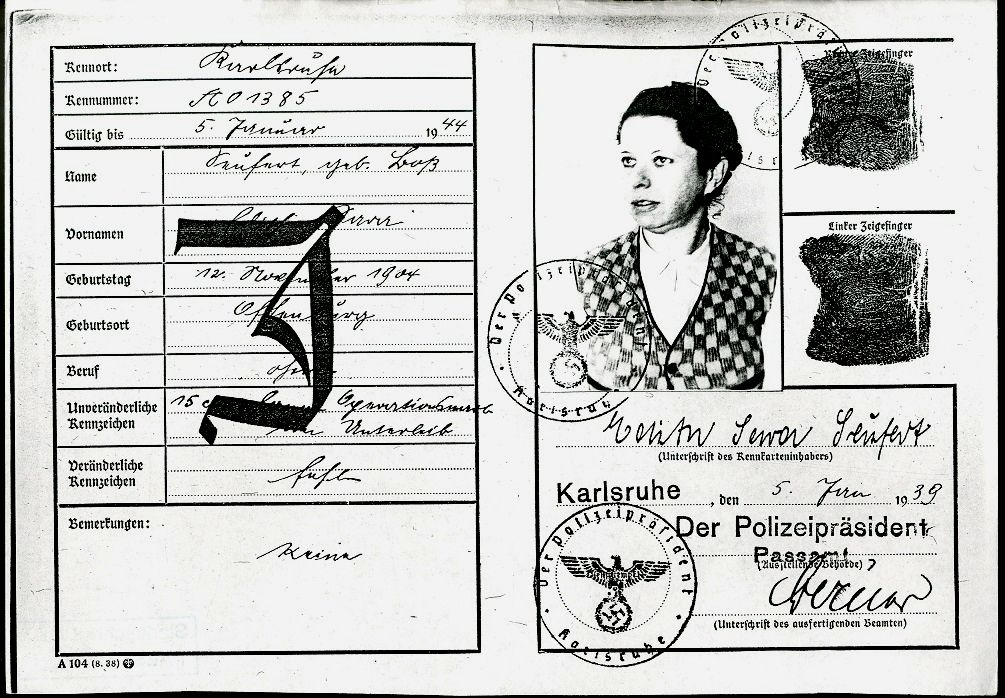

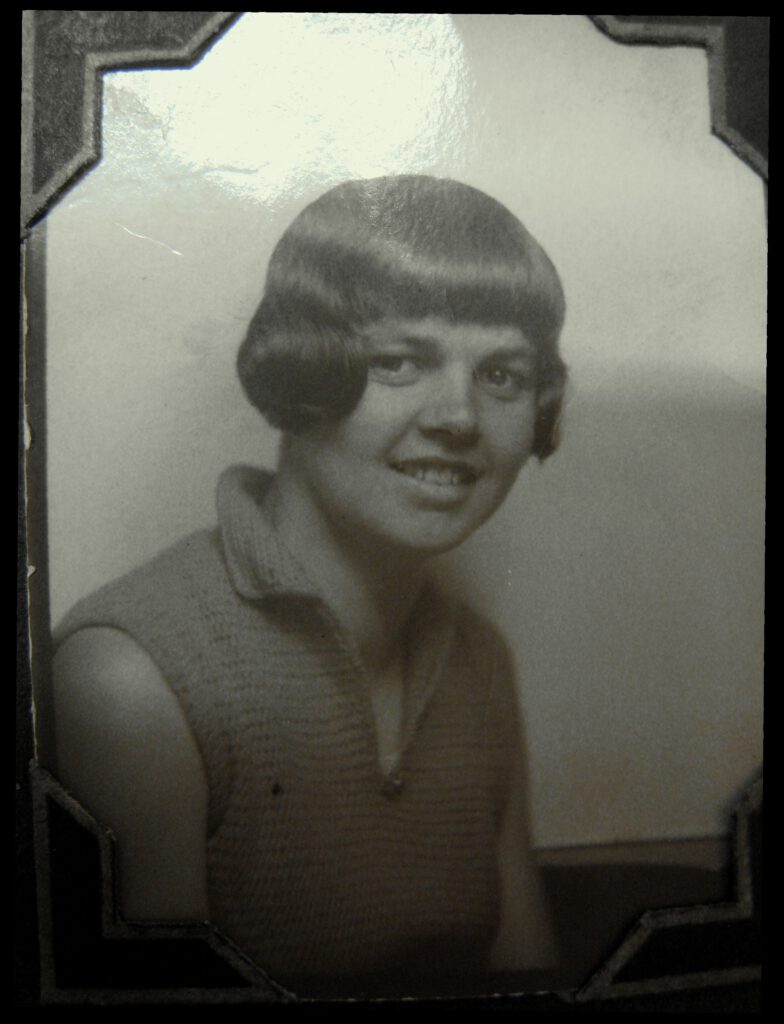

Berta’s daughter Edith also found a spouse: In October 1934 she married the mechanical engineer Karl Seufert, who was born in 1898 in Durlach / Karlsruhe into a Protestant family. Karl was an opponent of National Socialism and marrying a ‘Jewess’ was probably also an expression of his political stance. Edith and Karl, who had lived together in Karlsruhe since 1935, had a child, but their daughter, who was to receive her mother’s first name, died shortly after birth in 1936.

The Nazi dictatorship intervened in all areas of Berta’s family’s life. Heinrich Schidelko writes about the aggravated economic situation of the Villingen department store:

“When then at the time of National Socialism the harassment, restrictions and threats became greater and greater, the number of customers declined sharply. So he ( = Josef Boss, kmr) and his wife Berta had to give up the business in November 1935. He sold the house below value and moved to Stuttgart in March 1936.”

Berta, Josef and later Erwin Boss lived in Stuttgart first in Reinsburgstr. 185 in the 1939 address book one finds the entry of ‘Boss, Josef Privatier’ as a tenant in Scharnhorststr. 19 (since 1946: Rathenaustraße), which is located in the Weißenhofsiedlung. According to Nazi criteria, the owner of the house and his fellow tenants were ‘Aryan’; the entries in the Stuttgart address book of 1940 do not include the additional compulsory first names, ‘Sara’ and ‘Israel’, which Jewish Germans had to bear.

December 22, 1939 will have been a sad date in Berta’s life, as her husband Josef died at the age of 71 in Stuttgart’s Marienhospital. He was buried in Stuttgart’s Prague Cemetery, where the family grave still exists today.

Presumably, after Josef’s death, Berta’s daughter Edith Seufert moved to Stuttgart. From the address book of 1941 it can be seen that “Boß, Berta Sara We” initially continued to live at the previous address. In the course of 1941, however, the widow was evicted from her apartment in Scharnhorststrasse and had to move to Stuttgart’s Wannenstr. 16, a house that belonged to the Jewish lawyer Dr. Robert Mainzer and his wife Helene.

However, this was preceded by a catastrophe in Berta’s life: On December 1, 1941, her adult children Erwin Boss and Edith Seufert were deported from Stuttgart to Riga, where they initially had to live in the ghetto – subcamp Jungfernhof under life-threatening conditions.

Was the deportation also the reason that their mother was forced out of her familiar home? From around the same time, namely from October / November 1941, a short film has been preserved about the so-called ‘Judenladen’, which was set up in April 1941 at Seestraße 39 in Stuttgart. Contemporary witnesses also recognized Berta Boss in this film. Unfortunately, this knowledge was lost, so that we do not have a picture of Berta Boss.

About the background of the ‘Judenladen’ Maria Zelzer writes in her book ‘Wege und Schicksal der Stuttgarter Juden’:

“Any food, the farmed and the free, could only be bought in Judenladen, violators were threatened with concentration camp. After the Jews had to wear the star since September 1941, they were no longer allowed to use streetcars. So someone from Bad Cannstatt or Vaihingen had to walk to Seestraße for a loaf of bread, and it could happen that he was brusquely turned away because the goods were not there.”

Berta’s Stuttgart home addresses were not extremely far from the ‘Judenladen’, but just walking there as a ‘Sternträgerin’ must have been a gauntlet for her.

A list dated February 7, 1942 contains the names of Berta Boss and four other Jewish women from Stuttgart who were to be transferred to the forced residential home in Weißenstein Castle in the district of Göppingen. It is not known exactly when the Nazi authorities implemented this plan, but it was probably within a week of the date mentioned. A total of fifteen Stuttgart Jews arrived at the beginning of February 1942 in the neglected castle, which had functioned as a forced residential home since November 1941. After this influx, a total of 41 senior citizens were in the home, and the situation became cramped. Whether and if so to what extent Berta Boss was able to take furniture and furnishings with her to Weißenstein is not clear from the restitution files. Berta Boss lived at the Weißenstein castle for just under seven months.

On August 20, 1942, she and 26 other residents were transferred to the Killesberg camp in Stuttgart. After two terribly endured days and nights, the approximately 1000 Jews were taken by train to the Theresienstadt concentration camp ghetto. Here, the 70-year-old Berta Boss lived for about a month; on September 26, she was deported to the Treblinka extermination camp, where she was murdered.

As mentioned above, two of her children also fell into the clutches of the Nazis. Edith Seufert, née Boss is quoted in a restitution file from October 1948:

“My brother Erwin and I were deported to Riga on December 1, 1941. He then died about four weeks later in the Salaspils camp.”

The fate of Berta’s oldest child, Adolf Boss is just as terrible as that of his younger brother. Dr. Adolf Boss, a physician and communist who lived in Berlin, had fled Nazi Germany with his wife and child as early as 1933 and eventually traveled to the USSR in 1934 to work in his profession as a doctor. In 1938 he fell into the clutches of the Stalinist secret service and was sentenced to a stay in a penal camp. After another trial he was shot in 1942. Adolf’s wife Josefine was able to leave the Soviet Union with their son Valentin after many difficulties.

Berta’s daughter Edith, married Seufert had the improbable luck to survive the concentration camp ordeals, on January 26, 1945 she was liberated in the concentration camp Thorn near Danzig. When she returned to Germany, she found no home, for her husband Karl Seufert was also no longer alive. He had already died in a field hospital in Warsaw in August 1942. Karl had had to separate from Edith under duress, because as soon as his employers learned that he was married to a ‘Jewess’, he was dismissed. His forced professional odyssey ended only in March 1941, when he found employment with the Wehrmacht. The fact that Edith, who was married to a German ‘Aryan’ (‘privileged mixed marriage’), was deported during his lifetime is an extraordinary hardship and indicates that the Nazis specifically wanted to ‘punish’ Karl Seufert, an opponent of the regime, and his wife.

After the liberation, Edith Seufert lived in a camp for ‘displaced people’ in Stuttgart-Degerloch until 1948. In September 1949 she married the self-employed businessman Willi Steinmetz and lived with him in Frankfurt am Main until March 1959. The couple chose the town of Garmisch-Partenkirchen as their retirement home. But after only two years, Edith became a widow again. Edith Steinmetz, née Boss, widowed Seufert died on May 18, 1974 after a long illness in the district hospital of Garmisch-Partenkirchen.

Berta’s daughter-in-law Josefine Boss first lived in England with Berta’s grandson Valentin, and in 1959 they emigrated to Canada. Valentin Josef Boss became a professor at Mc Gill University in Montreal, the city where he died in 2015. His only child, Berta’s great-granddaughter Sylvia Boss also lives in Canada.

From the immediate Boss family were murdered in the Shoah: Berta’s brother-in-law Dr. Siegfried Boss, who fled to his death. His widow Klara Boss, née Selten was imprisoned in the Theresienstadt concentration camp at the same time as Berta, where she died on January 12, 1943.

Alma Hirschfeld, a half-sister of Berta’s husband Josef was murdered in the Auschwitz death camp in January 1943.

Victims from the Heimann family are Berta’s brother Leo Heimann, he died violently on December 18, 1944 in the Groß Rosen concentration camp. Berta’s sister Else Glaser, née Heimann, nine years younger, was deported to the Auschwitz death camp on June 29, 1942, together with her husband Emanuel.

Since 20 October 2021 there are Stolpersteine in front of the house Obere Str. 1 in Villingen in memory of Berta, Josef, Adolf, Erwin and Edith Boss.

Our text is based on the thorough preparatory work of members of the Initiative Pro-Stolpersteine Villingen Schwenningen e.V. . We also owe them the photos of Edith, Adolf, Valentin and Josefine Boss.

(10.05.2023 kmr)

Leave a Reply