Bahnhofstr. 4

In 1783, Seligman Mendel, born in 1756, and Fratige Michael, born in 1758, a Jewish couple, settled as ‘Schutzjuden’ [protected Jews] in Jebenhausen, where a Jewish community existed since 1777. Seligman and Fratige came from Fürth/Bavaria. However, Seligman’s family might not have originated there instead came from nearby Dettelbach (County Kitzingen, near Wurzburg) because on their arrival in Jebenhausen he took on the family name of Dettelbacher. The Dettelbachers belonged to an old established Jebenhausen and later Goppingen Jewish family. In Jebenhausen, the Dettelbachers owned several houses, most of them located at Boller Street, which are still standing today. There were only a few professions open to Jews at the time before emancipation, and many were limited to being cattle or horse dealers, weavers and innkeepers. Only later would there be farmers in the Dettelbacher family.

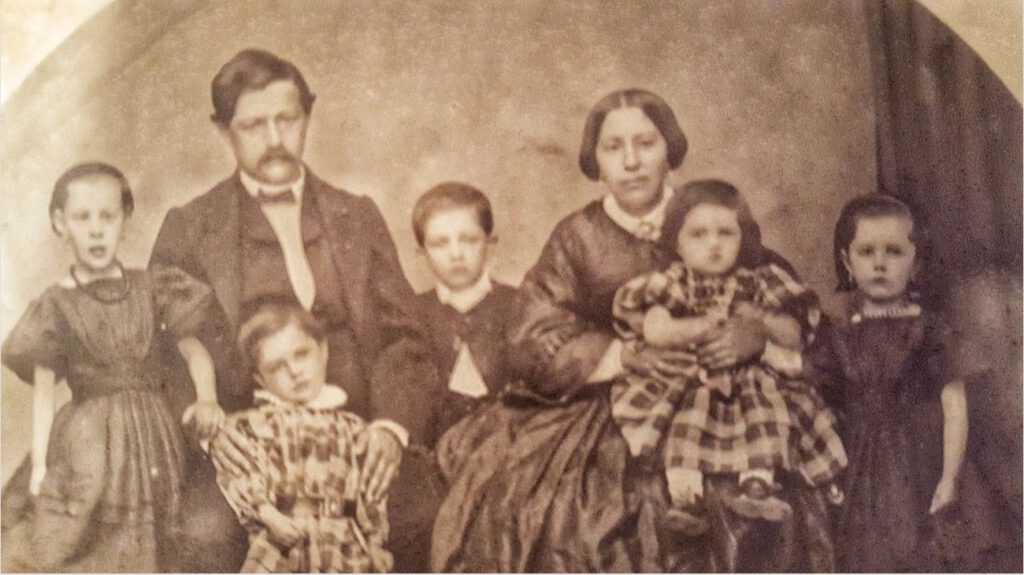

A grandson of the first immigrant settling in Jebenhausen is Meier (Maier) Dettelbacher, born 1829, a butcher by profession. His five siblings emigrated to the United States, but Meier was content with the moving from Jebenhausen to Goppingen via the Eichert hill. In the August 13th , 1862, issue of the Goppingen weekly newspaper, he posted the following polite announcement:

Goeppingen Change of House Address andRecommendation.

I would hereby like to inform the esteemed public that I have changed my residence from Jebenhausen to Goppingen and am living in a house, which I have purchased from Mr. Schauffler, right next to the railroad station. I will continue to operate my butcher shop with all due circumspection and would like to recommend my merchandise which is produced with fresh beef and calf meat. Meier Dettelbacher Butcher‘

By mentioning beef and calf meat, Mr. Dettelbacher gave an indication that he would be running a kosher butcher shop. At that time, the butcher shop was located near the railroad station, which had been constructed in 1847, and this was most certainly an excellent location for the shop. The business seems to have flourished, and most likely the building was replaced in 1875 by a larger one which could also be used for other purposes. Shortly thereafter a restaurant was added which offered guest rooms as well as a hall that could be utilized for celebrations and performances.

Meier Dettelbacher was married to Jette, née Sontheimer, and the couple had ten children. Only one, their son Max, followed his uncles and aunts through emigration to the USA. Another son, Sigmund, will carry on the profession of his father and, as a master butcher, will be instrumental in the founding of the Goppingen butchers guild. Two boys and eight girls are the descendants of Jette and Meier, but only three of them will also have descendants of their own.

Frida: Organizer and Hostess

Daughter Frida (Frida) was one of their children who remained unmarried and childless. She is born as the third-youngest child of the couple on June 13, 1868, in Goppingen. Not much is known about her life. However, a short notation in Rabbi Aron Tänzer’s book ‘The Jews in Jebenhausen and Goppingen’ gives a hint of a small ‘cultural revolution’ in Jewish Goppingen in which she participated. Tänzer writes:

“People who served as organists in the former prayer room and the synagogue:

1870 – 1882 M. Grunewald

1882 – 1886 Music teacher Enderle

1887 Gress

1888 – 1896 Frida Dettelbacher”

At the age of twenty, Frida takes over the office of organist for eight years. The law at that time does not even consider her as being of adult age, especially for a woman. By the way, her predecessors did not belong to the Jewish congregation. There was a conflict of opinion among Jewish Germans regarding the use of an organ in a synagogue. For Orthodox Jews, this was a difficult adaptation to Christian liturgy and was considered a sacrilege. In their opinion, instrumental music (as an expression of the joy of life) should not have a place in Jewish religious services, which should only express mourning because of the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem. The Liberals answered with more pragmatic arguments: in order to assure attendance (and enjoyment) of Jewish religious services, they should express emotions and dignity, and the organ was especially suited for this purpose. Besides, the ‘Feeling of Being a German‘ might have played a special role because the organ was considered the instrument of the German-Lutheran Protestant Church.

Frida was not the only one in her family who had special musical talents: her sister Sophie was married to Carl Bodenheimer, the Goppingen Cantor, her nephew Julius Krämer was also a Cantor, her niece Klara Hanauer was a piano teacher.

Frida probably spent her everyday life at Hotel Dettelbacher. She and her two younger unmarried sisters Eleonore and Berta ran the hotel and restaurant. Max Krämer, who was not a family member, took over the butcher shop after Sigmund Dettelbacher’s death in 1909.

Margot Karp, grand-niece of Frida Dettelbacher, shared the following memories from her childhood:

“Frida was the tallest of the Dettelbacher sisters, I think – but by the time we knew her she was rather bent and thin. She seemed to us to be in charge of the kitchen in the Hotel Dettelbacher – and we as young children were occasionally allowed to come visit there – and they gave us rolling pins and let us roll out dough – and shell peas or some other little chores where we could do little damage. And we watched, and we sampled some of the food, and loved the smells and the atmosphere. I also remember the Wurst (sausage) samples we got to try from the butcher shop in the hotel, which were eaten with great glee. I remember Anne [M. Karp’s sister, annotation by author] and me being there in the kitchen (I was also treated once to lunch in the dining room where I was served whatever I chose from the menu – I could barely read – and it was an enormous event for me!) – and then we misbehaved and were banished. Our ‘greatest crime’ was when we went out into the backyard of the hotel where a motorcycle was parked (either one of the worker’s or a guest’s) – we climbed onto the seats, and the bike fell over – something broke – and a furious and probably frightened Tante Frida yanked us up, and from then on we were expelled from the kitchen forever. At least that’s how I remember it.“

The Dettelbacher Hotel’s importance for the Jewish community during the Nazi years was central: it became the location for the Gemeinde’s [community’s] activities – the Kegel Verein [bowling league], Merkuria, Purim Spiele [Purim plays], Vortraege [lectures], concerts – and of course the afternoon Kaffees [get-togethers for coffee], and THE restaurant when all other locations became closed to us. And Tante Frida was in charge, I think.”

Margot Karp’s memories are also supported through other sources: in 1936, the hotel was rented by the Goppingen Jewish community, and the building became the official ‘Gemeindehaus’ [parish hall] which in reality it had already been during the previous years. It is mentioned, for example, that the annual Chanukah-Festival celebrations took place there, where Jewish children and young people put on wonderful performances. No other building besides the synagogue was identified with the Goppingen Jewish community as much as the ‘Dettelbacher’, but this did not prevent non-Jewish guests from visiting the establishment in better days. The following dedication appeared in the ‘Israelite Weekly Newspaper’ on the occasion of Frida’s 70th birthday:

“On the 13th, Frida Dettelbacher’s 70th birthday was quietly celebrated. Until a few years ago, the honoree was in charge of the well-known Hotel ‘Dettelbacher’, which she operated together with her sisters and Max Krämer, who in the meantime has emigrated. From the days of her youth until the evening of her life she fulfilled this task with never-tiring diligence. It is mainly due to Frida Dettelbacher’s achievements that this restaurant does not only have an excellent reputation within the Goppingen community but also in the surrounding area. She always worked with total dedication to make sure that the kitchen and hotel met all the needs of the guests. Therefore it was also noted with true regret that she started her well-deserved retirement in 1936 – at the age of 68 – and left the exhausting demands of the business in younger hands […].”

Destruction during the Pogrom Night

During the Pogrom Night (Night of broken glass) on November 9, 1938, the Nazis’ hatred of the Jews was also directed toward the ‘Hotel Dettelbacher’, which was damaged on the inside as well as the outside. It is not known if Frida Dettelbacher was in any danger herself, because we do not know if she was still residing in the building at that time. Anni Kahn, whose married name later was Ostertag, worked as a waitress in the restaurant and lived in the hotel. She remembered that shots were fired at the building.

After the death of her sister Berta in 1933, Frida Dettelbacher became the co-owner of the property and the building; the other half belonged to Max Krämer who run the butcher shop. In 1939, sales negotiations with the City of Göppingen commenced under their management. Most likely the two owners were experiencing difficult financial conditions. This probably was due to the decrease of their customer base because many Jewish Göppingers had fled by then and ‘Aryans’ were not allowed to enter the building any longer. Therefore the sale of the property on March 29, 1939, to the City of Goppingen took place under forced circumstances. On June 16, the City administration already had the building torn down. Contrary to newspaper announcements, the City did not construct a new building. Most likely it was more important to the Nazi city government to destroy a symbol and landmark of Jewish Goppingen than to utilize it as a building site. (The City also acted similarly in regards to the property on which the synagogue had stood). A private request for a building permit after the end of the war was also denied because at that point the return of the property to Frida Dettelbacher’s heirs had not yet taken place.

Cared For By Her Sister Sophie

Where did Frida Dettelbacher live after she had to move out of the hotel? A letter dated April 19, 1942, written by Hedwig Frankfurter to Emilie Levinger, Frida’s niece, gives an indication: “[…] Your aunt Frida is your mother’s [= Sophie Bodenheimer, née Dettelbacher, Frida’s older sister, annotation by author] faithful companion who shares the love and worries about her nieces and nephews with all her heart. They live together in a very large room which – separated by a divider – serves as their living and bedrooms and seems very roomy. You would recognize many of their old furniture, pictures etc. and would find this home rather comfortable.”

Described here is a room at today’s Morike Street 30, a ‘Jewish house’ to which the sisters and other Goppingen Jewish women of Göppingen had been forcibly relocated.

Castle Dellmensingen – A Ghetto for Jewish Seniors

Already a few weeks later they are again forcibly moved. Hedwig Frankfurter writes to Thilde Gutmann on July 22, 1942:

“Frida Dettelbacher is very ill and in a lot of pain; in the near future, she and her sister are going to be sent to a rest home.”

The rest home that she is referring to is the Old Castle in Dellmensingen, between Ulm an Laupheim, which had been designated as a compulsory old age home for Jewish people. Frida, who was deathly ill with intestinal tuberculosis, already passed away three days after on August 7th and was buried in the Jewish cemetery in Laupheim. During that time, this was not a given! Sebastian Ganser, a Laupheim citizen, deserves the credit for it. He was a farmer who was politically active in the Catholic Centrum Party and remained faithful to his lifelong convictions and ideals even during the Nazi rule. His grandson Markus Ganser explains: „It was reported that Ganser aided Jewish families in their flight. As the driver of the hearse he was responsible for the transport of the deceased in Laupheim. He repeatedly drove outside of the city limits if someone had died at the residences in Heggbach or Dellmensingen. Thus he made it possible for victims of the Nazis to at least receive a dignified burial at the Jewish cemetery in Laupheim.“

It could not yet be detremined when the burial actually took place, but we know that the tombstone was placed in July 1955. The initator of the tombs was Helmut Steiner, a Jewish son of Laupheim, who survived during NS-times in St. Gallen / Switzerland. On November 20, 1953 he wrote to a Jewish trust company: “But worst is that on the cemetery so many victims of National Socialism were buried. ( … ) My demand is that from the property which has been created by selling the former community property modest tombstones could be bought ( … ). (We owe this document to the town of Laupheim archives.)

Frida‘s illness could probably not have been cured, taking into consideration the state of medicin at this time, even given different political circumstances. However, all the enforced moves and depressing lifeconditions must have made Frida‘s last years even more difficult.

Frida’s sister Sophie Bodenheimer, who most likely had stayed in Nazi Germany to look after her gravely ill sister, died in 1943 under murderous living conditions at Theresienstadt concentration camp, a fate that the Nazis also had planned for Frida Dettelbacher.

Frida’s nieces Jenny Krämer, who lived in Kassel, and Frieda Krämer, living in Nuremberg, were also murdered by the Nazis. Both were the daughters of Flora Krämer, née Dettelbacher, Frida’s sister who had been eight years older than her.

Mrs. Margot Karp, to whom we owe so many memories of Frida Dettelbacher, was born Margot Bernheimer in Göppingen in 1924 and died in New York in February 2023.

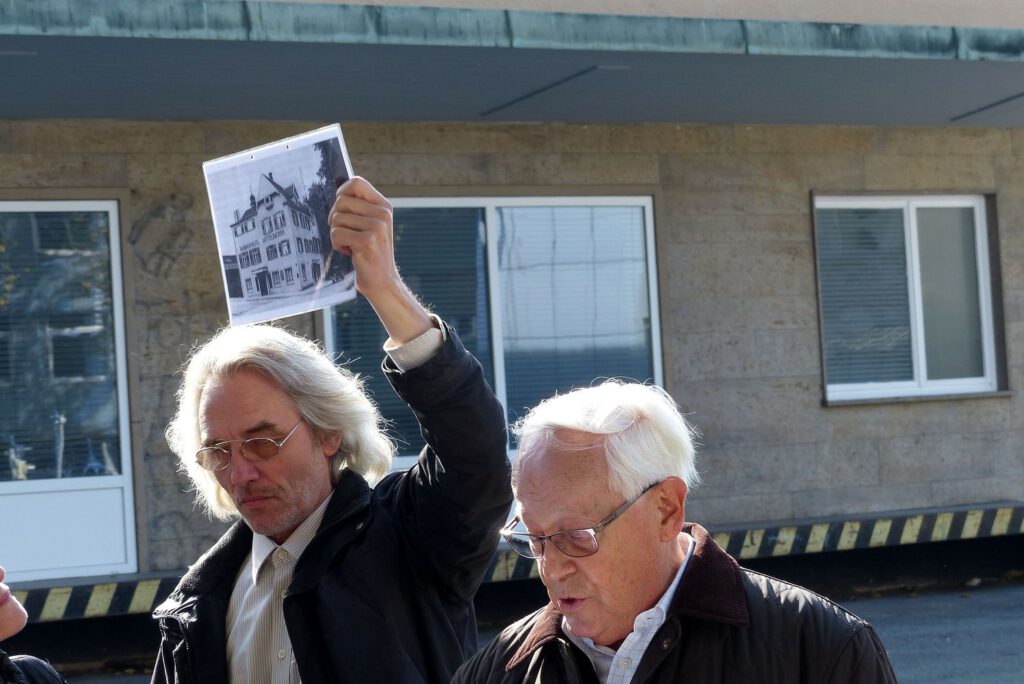

On October 2nd, 2013, a Stumbling Stone was placed in memory of Frida Dettelbacher. Mr. Frank Jakoby-Nelson, a grandnephew of Frida Dettelbacher, adressed the commemorative. The ground on which the Hotel Dettelbacher stood is now part of the redesigned station forecourt.

(08.05.2023 kmr)

Leave a Reply