Jahnstr. 5

He as young, he was gay, he could not live self-determined: Arthur Schrag died at the age of thirty-five in the KZ (concentration camp) Flossenbuerg. Possibly, this man is the one on our website of whom we know least. There are almost no records on him, no single object exists remembering him, and the members of his long-established Eislingen family today are not able to report on him. “We did not talk about him.” Thus Arthur Schrag is one of those to whom Hans Magnus Enzensbergers poem refers: “Nobody can remember them.” But nevertheless we know some details:

Arthur Schrag was born in Eislingen on February 13th , 1907 and lived finally in Jahnstraße 5. On May 8th, 1942 he died in KZ Flossenbuerg. He was the youngest of fourteen children of the Protestant couple Hermann Alfred Schrag (June 4th 1861 till Dec 6th 1919) and Dorothea Schrag née Hansch ( Aug 28th 1863 till July 9th 1909). When he was two years old his mother died, his father died when Arthur was twelve years old. So he came to the house of his sister sixteen years older than him, Emilie Maunz née Schrag who together with her husband had to be the parents to the young boy. On April 3rd 1921 he was confirmed in the nearby Christuskirche – the entry in the parish book there is the only find in Eislingen of Arthur Schrag.

What must have been the situation for the young man, when he felt that he liked young men? The time in which he was born made things difficult for him. We do not know if his homosexuality was known in his family. Maybe he lived totally in secret and denied such an important part of his personality? Maybe people talked of him? Maybe there were even controversies in the family? Threats? One was proper Protestant.

One lived in a small town where almost everyone knew everyone. Thus it might be OK that Arthur became “a travelling businessman”, possibly “a travelling salesman” and was on the road very often. We do not know.

The church records hand down Arthur’s confirmation line. This can be read with sorrow today. The minister considered in choosing the line that the candidate for confirmation had lost both his parents at an early age, he certainly did not choose by chance the following words from Psalm 27, 10: “For my father and my mother have forsaken me, but the LORD will take me up.” The minister at Christuskirche today (2019), Frieder Dehlinger, who checked the church records, sent the notes on Arthur and commented on the confirmation line with the words: “The confirmation quotation could today be understood as Father State and Mother Church.” Arthur Schrag was first often “a person left alone” and he became really “a person disappeared”.

His Christian belief must have been important for Arthur Schrag. In the file card that was sent from KZ Flossenbuerg to the Criminal Investigation Centre Stuttgart there was, rather unusual, a bible. But let us go a few steps back in time!

The gay travelling salesman must have attracted attention by the police. Maybe during one of the raids which then had been executed at gay meeting points? We do not know that. In any case Arthur loved the wrong way, his homosexual desire was not allowed by the German Criminal Code § 175. This infamous paragraph existed since the times of the Kaiser, the German Empire, exactly since January 1st 1872, it continued to exist in the Weimar Republic, was tightened in the National Socialist Third Reich in 1935 and then – incredibly, but true! – in this tightened form taken over by the Federal Republic. In several steps it was de-activated and finally on June 11th 1994 completely taken off the German Criminal Law. Arthur was one of about 140,000 German men who were convicted of § 175. No wonder that a contemporary of Arthur who lived in Eislingen as an expelee from Czechoslovakia, the writer Josef Mühlberger (himself convicted of § 175 in the forties) spoke of the “paragraph of disgrace”.

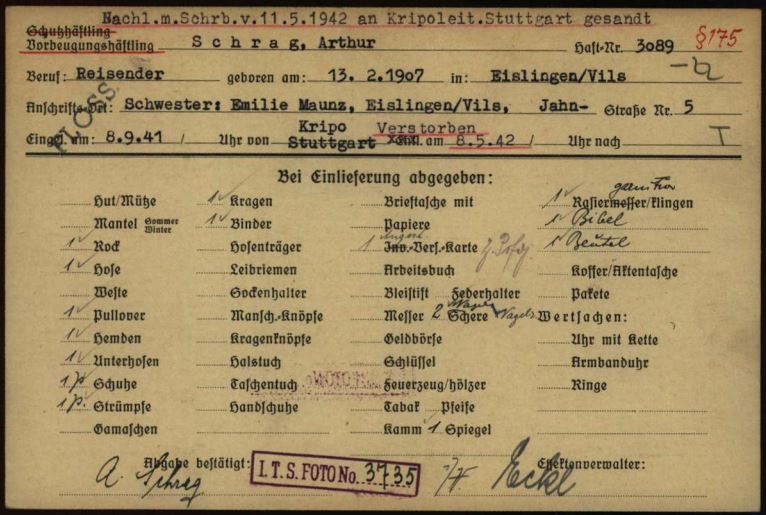

Arthur was, where and how ever, “discovered”. On January 17 th 1940 he was taken to the Mannheim prison for people awaiting trial where he was registered with prisonerbook number 1898, shortly afterwards on January 20th 1940 he was transferred to Dieburg prison. Reason: “Sexual offence”, prison term: two years. Finally on September 8th 1941 he was put in to KZ Flossenbuerg by the Stuttgart Criminal Police. There he was given the prisonernumber 3089, according to Nazi categories he was a “Vorbeugehäftling (prevention prisoner)” because of §175. He died on May 8th 1942, as cause of death “acute heart death” was noted.

With German Gründlichkeit (thoroughness) all the objects who had to be handed over when he entered KZ Flossenbuerg were listed there, kept and after his death sent back to the Stuttgart Criminal Investigation Unit. The file card of the concentration camp consisted of a pre-printed list of objects with some space for additions. On the card the following belongings of Arthus were listed. 1 jacket, 1 pullover, 1 shirt, 11 underpant, 1 pair of shoes, 1 pair of stockings, 1 collar, 1 tie, 2 nail scissors, 1 shaving set, 1 bag, 1 bible (…) The bag and the bible had to be added in writing. What happened to those objects later, we do not know. Here too Enzensberger’s words are true: “Nobody can remember them.”

He was young, he was gay, he could not live self-determined: Arthur Schrag from Eislingen died at the age of thirty-five years in KZ Flossenbuerg. In 2019, in which year the Stolperstein was laid, worldwide the so-called “Stonewall Riots” of the days following June 28th 1969 in New York are remembered, when for the first time homosexuals and transsexuals put up a fight against the continuing raids of the police at their meeting points, as the bar Stonewall Inn in Christopher Street. This event was encouragement and inspiration of the Gay Liberation, the civil rights movement for people like Arthur Schrag. And if we look at the situation of gay, lesbian, bisexual, transexual,intersexual and queer people in today’s world we realize: There is lot to do.

(04.04.2019 ts)

Leave a Reply