Frühlingstr. 29

Sofie Bodenheimer was a born Dettelbacher and by this name Goeppingen people thought until the Nazi-era of the Hotel/Restaurant at the train station, which had been founded by Sofie’s father – Meier Dettelbacher in 1862. It was destroyed in 1939 by the local government of the Nazis.

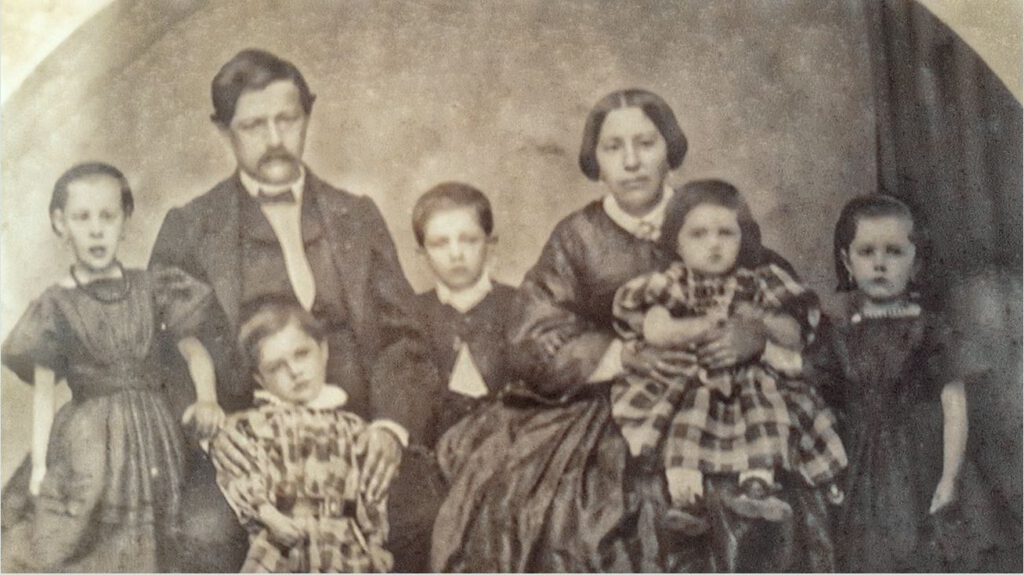

The parents of Sofie, Meier and Jette Dettelbacher, had 10 children and Sofie was the fifth of the brothers and sisters. Although documents mention the city of birth as ‘Jebenhausen’, Sofie was the first of child of the family to grow up in Göppingen. Almost to the day, exactly a year after the move of the family from Jebenhausen to Göppingen, did Sofie come into the world on 14.08. 1863. Thus, she grew up in the Hotel and probably as a girl anyway had to help out in the business.

Fanny, Sigmund, Moritz, Sofie and Flora (from left)

Afterward the birth of brother and sisters, Max *1865, Hanna *1866, Frieda *1868, Leonore *1870 and Berta *1872 she made herself useful as caretaker of the little ones.

The Cantor’s Wife

1888: Sofie Dettelbacher, 25 years of age is thinking of marriage: Carl Bodenheimer, 3 years older than Sofie and living in Goeppingen since April of 1881, is her fiancé.

About his life, Göppingen Rabbi Dr. Aron Tänzer writes:

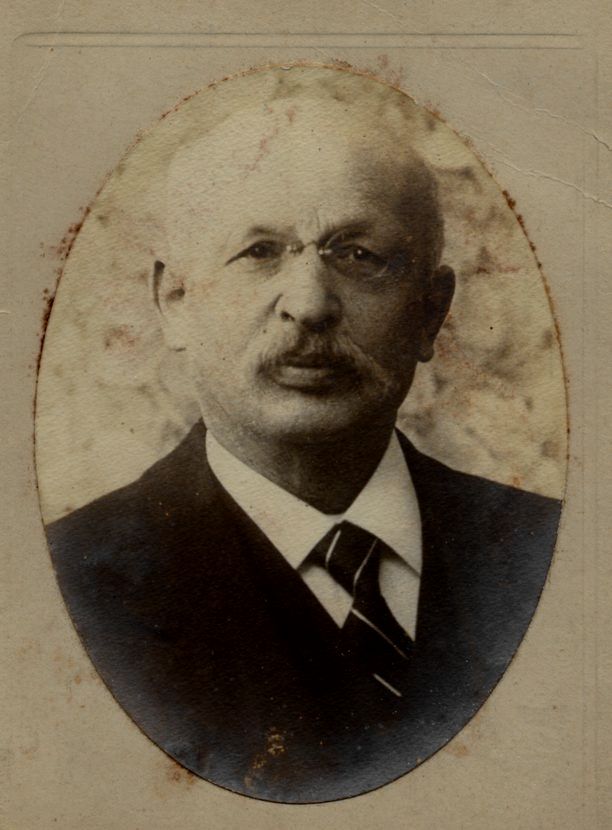

“Carl Bodenheimer was born on 9 June 1860 in Diersburg (Baden), son of a teacher and cantor. He completed his teaching seminar in Karlsruhe and was then a teacher at the denominational school in Kuelsheim but had to give up this position when the catholic parents refused strongly to send their children to a Jewish teacher in the school.”

Thus Carl Bodenheimer had careerwise only a working sector within Jewish institutions. In Goeppingen in April 1881 he would have been gladly accepted for an unlimited contract as cantor, but he first had to complete the Cantor Examination of the State of Wuerttemberg and to study further for a 2nd Teacher Examination. Sofie and Carl apparently did not want to wait until the final determination and absolute hiring on July 1891, so they married in Goeppingen on 6 August 1888.

Rabbi Dr. Taenzer had for his ‘colleague’-cantor only words of praise: “He enjoyed the high standing in all circles of the town, and he was equally looked upon favorably in the arts circles where he was involved with success. He was for many years the Director of the former choral society ‘Germania’ which then merged with the ‘Liedertafel’ Society, he gave singing lessons at the ‘Harmonie’ society, at the firm of A. Gutmann & Co. and was an honorable member of the “’Liedertafel’ and ‘Sängerbund’ Societies. He earned special merits from the ‘Merkuria’ Society, where he acted as librarian for many dozens of years and where he embellished events through song and play”.

Sofie’s life disappears almost behind that of her husband who is in the public eye, and is admired and appreciated. Only her participation in the ‘Jewish Women’s Group’ shows that she did not merely stand at the ‘kitchen stove’.

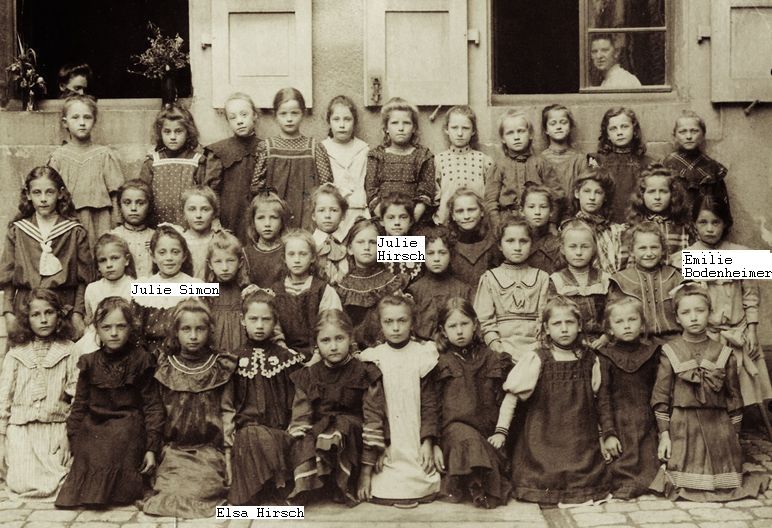

The Bodenheimer family had four children: Max was born in 1889, Ludwig in 1890, Emilie in 1898 and Jette in 1902.

There are photos of the two girls in the Goeppingen archives: Emilie (Emmy) as a student at the Higher Girl School around 1908/09, Jette at her Bat Mitzwa (confirmation) in 1918. Apparently, great importance was also given to the good education of the daughters.

During the First World War, while Aron Taenzer had to report for duties as battle field rabbi, Carl Bodenheimer had to take over some of his duties. It is obvious that Sofie as well had the bear some of the burden. It was surely comforting for the Bodenheimer couple that none of their two sons had to go into the war.

In the years after the war, the name of the older daughter Emilie came up quite often in 1919 as treasurer of the ‘Israelite Young Women’s Group’, in 1923 as secretary for the ‘Israelite Youth Group’. The sad point in Sofie’s life was described by Dr. Taenzer in the following words:

“Bodenheimer became ill in August of 1924, his duties were taken over by a substitute, and he passed away on 8 February of 1925, deeply mourned by all.”

There is little to report about the next 10 years of Sofie Bodenheimer’s widowhood. Did she help her sisters in the running of the Hotels/Restaurants? Her children left Germany little by little – on their free will or by force:

Emilie, who lived with her husband Fritz Levinger in Berlin, moved to Argentina. The couple did not have any children.

Jette (Jettchen) lived in Ludwigsburg with her husband Hermann Kaufmann and daughter Ellen, who was born in 1927. They were Jette and her family were able to flee to Santiago de Chile in June of 1939 where Jette died in 1973.

Sofie’s daughter Ellen, widowed from Alvin Cohen, lives in the USA, as do her daughters with their families.

Ludwig Bodenheimer who worked as a salesman in Stuttgart, fled with his wife Lilly and daughter Susan who was born in 1926 to New York in the USA in 1939. Ludwig died in 1962 in his new home country, his daughter Suse, who had married Norman Seif in the USA, died in 2004. Her sons live in the USA.

Sofie’s oldest son Max Bodenheimer had emigrated to the USA long before the Nazi time.

“Oma had the special skill to calm me down”

Some pictures show Sofie at the end of the 1920s in Goeppingen with her granddaughters Ellen Kaufmann (Jette’s child) and Suse Bodenheimer (Ludwig’s child).

After the death of her husband she moved out of the quarters of the Rabbi’s house (Freihofstrasse) and moved then to Marstallstrasse 43, where the pictures with the granddaughters were taken.

Of the visits to Grandmother in Goeppingen, Ellen Cohen, née Kaufmann has a very distinct memory. “I was at Oma’s when a terrible storm began, with loud thunder and lightening frightening me. But Oma had a special skill to calm me and explain to me the laws of nature.”

Margot Karp, whose grandmother, Hanna Simon, was Sofie’s younger sister, can also contribute childhood memories: “We made courtesy visits (Anstandsbesuche) mostly with our mother; later, in our last winter in Göppingen (=1938 kmr), I remember going there alone. The community had undertaken a collection campaign against hunger, copied from the official ‘Eintopf Sonntag’ (Stew Sunday): you were to contribute the amount of money you didn’t spend on an elaborate Sunday meal to this campaign for needy members of the community; the few adolescents in the community were given collection boxes and a list of names where they were to pick up contributions; we were to be extremely courteous and to spend a bit of time if our donors wanted to have a conversation. Tante Sofie was on my list, and I remember her being welcoming and sweet – and happy to see me.”

These memories give an indication that Sofie Bodenheimer was still living in comfortable circumstances during the middle 1930’s. That that was not taken for granted is reflected in the numbers of those who were supported by the Jewish Winterhilfe 1935/36. Those numbers were 39 people which then made up almost 12 percent of the Jewish population of Göppingen.

Silcherstrasse 17, nowadays Justinus-Kerner-Str. 17, is given in the 1937 address book as her next domicile. That was also where Max Krämer is registered who ran the butcher shop at ‘Dettelbacher’s’, so at least a well-known person lived there as well. The statement of the Jewish Community of Goeppingen for the year 1937 contains a surprise: at the age of 74 Sofie undertook for a short period of time the duties of her long dead husband by giving Jewish Religious classes and was remunerated for this. She probably helped thereby the Community between the death of Aron Taenzer in February and the taking over of the duties by Rabbi Wallach in November 1937. By performing these duties, Sofie showed that she was not only the ‘wife of the cantor’ but also had her own deep knowledge.

1939 showed Sofie’s address as Frühlingstrasse 29, a house which belonged to the Jewish family Veit. There is no evidence that she was forced to move. The move away from Silcherstrasse could also be related to Max Krämer’s flight to the USA, which occurred in 1938. It should be noted that the Jewish community used a room in the house at Frühlingstrasse 29 as a prayer room after the Synagogue had been destroyed during the Pogrom Night.

In a letter dated 19 April 1942 written by Hedwig Frankfurter to Sofie’s daughter Emilie Levinger in Argentina, one can find the last traces of Sofie’s life:

“Dear Mrs. Levinger! Although it has been some time since I last wrote you, I have been up to date on your and your husband’s state of health through your mother. It has become an understanding that when we are together she tells me of your letters and always beams with happiness that she can tell me good news. To remember our children takes most of the time of our thoughts. Your mother is astoundingly spright and her serenity and calmness are always a positive example for me. But the basis of such nature must be inborn. Your aunt Frieda is a loyal life partner to your mother, distributing love and care for nieces and nephews from the heart. They both live in a large room that, separated, serves as living and sleeping quarter and is still roomy. You would find many old acquaintances in furniture, pictures, etc. and take in the comfort of this home. In this respect, therefore, you need not worry. “

The good-hearted Hedwig Frankfurter obviously sees to it that Sofie’s daughter Emmy be reassured about her mother’s situation. Mrs. Frankfurter however must have been realizing that Nazis would censor the incoming letters. The narrowed and improvised circumstances, however, under which Sofie and Frieda are living become very apparent. The descriptions do not seem to apply to the Frühlingstrasse home but rather to the house on Mörikestr. 30 where the sisters were forced to move in December of 1941.

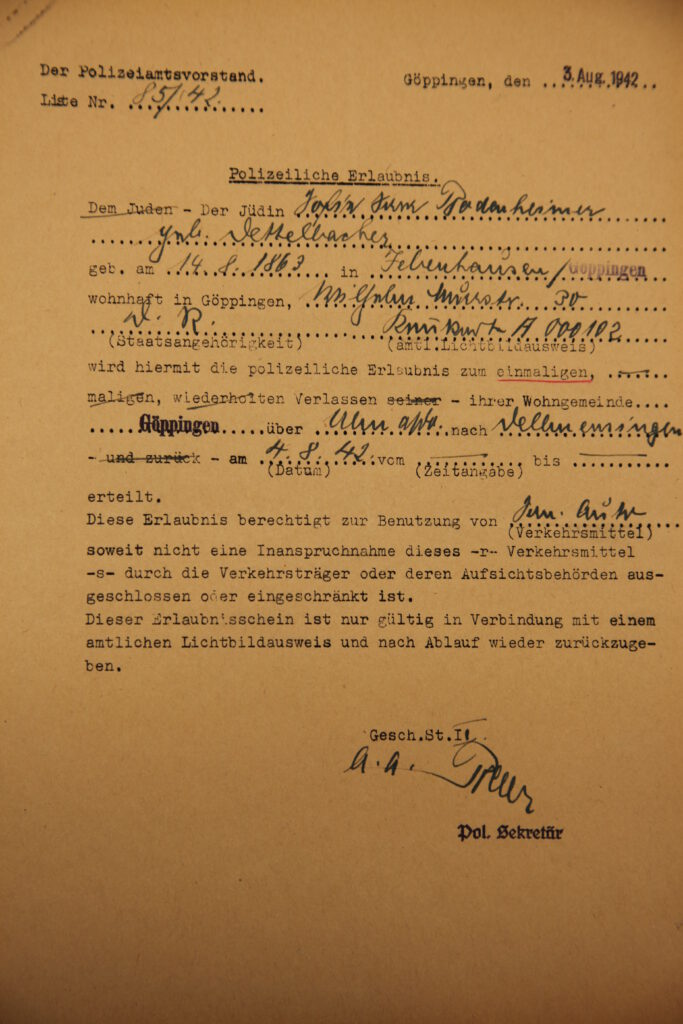

Dellmensingen, Theresienstadt

From Hedwig Frankfurter’s letter dated 22 July 1942 it can be seen where now Sofie Bodenheimer had to move.

“Frieda Dettelbacher is very ill and suffering pains; she and sister Sofie Bodenheimer will next have to go into a home.”

The ‘home’ mentioned is the old castle in Dellmensingen which from 23 February to 21 August 1942 was the compulsory old age home for Jews, most of them coming from Stuttgart and surroundings. Altogether 127 people had to live in the castle, 18 of them died during their stay.

Hedwig Frankfurter informs her friend Thilde Gutmann on 14 August that “Frieda Dettelbacher died 1 – 1/2 days after her arrival at the old age home of Delmensingen and was buried in Laupheim. Now Mrs. Bodenheimer, who long ago could have gone to live with her children but did not want to leave her sister, is left alone”.

There are controversial descriptions of the living conditions at castle Dellmensingen but compared to what the nursing home inmates expected, life in the old castle was still humane. Sofie Bodenheimer stayed here only 2 weeks, then she and the other 100 old people have to leave the castle.

From the restitution archives we hear that:

“At the time of the deportation the Jewish inmates of the castle Dellmensingen were deported to Erbach-Ulm 3-4 km away and were allowed to take with them only necessities. The rest of the possessions were taken in by the Finance Office of Ulm as per then existing regulations.”

The deprived were then brought to Stuttgart by train. What awaited them there was described by the Ulm nurse Resi Weglein:

“Arrival in Stuttgart, transport via buses, ride to Killesberg, take-over by the Gestapo. Immediately upon entering the exhibition hall there were body searches during which my husband’s watch with chain and money were taken. Killesberg ! That horror night remains unforgotten. 1076 people, mostly over 65, sat on chairs and had to sleep in that condition. About 50 very sick patients had bad sleeping quarters … next to us were two critically ill men on a mattress. One of them, Dr. Robert Gutmann from the Dellmensingen home, had lost his mind in this chaos and laid himself on his paralyzed neighbors chest. Eight poor old people died that night, we left 12 deathly sick behind.”

The next day the train went from the Stuttgart Northern station to the concentration camp Theresienstadt. Later Sofie Bodenheimer might have met up there with some friends and acquaintances from Goeppingen as she too is quartered on the floor of the roof of the Dresden barracks. About this place of agony Johanna Gottschalk writes from her own experience:

“Most of the transported people were placed on the roof’s floor of Theresienstadt’s “Dresdner Barracks”, i.e. the people were lying on the floor, during the first weeks without anything underneath, only with what they were wearing on their bodies. The toilets were on a lower level and there were few of the older people who could reach them in timely fashion, since most of them were ill with diarrhea during the first days.”

Theresienstadt: What did the people in Göppingen say when their Jewish neighbors were being deported there in 1942? What should they have known in Göppingen, what must they have known about this place? Frank Jacoby-Nelson, the then-twelve-year-old grandnephew of Sofie Bodenheimer, lived in Argentina with his family during that time. He remembers: “I once happened to come upon my mother and her sister Friedel Spielmann when they were crying. The word ‘Theresienstadt’ was mentioned but I was not given any detailed information about this. (…) I wondered why the name ‘Theresienstadt’ would make them cry because it sounded so pretty.”

So it was possible that these facts were already known thousands of miles from Theresienstadt. Sofie Bodenheimer already died on 24 September 1942 under these murderous circumstances. On the ‘Death Notice’ the (Jewish) doctor puts ‘Heart Asthma’ as the cause of death. He had to fill out the column and could not indicate the true cause. But for sure Sofie Bodenheimer died from a heart condition since her heart had been broken by the Nazi-Germans.

Sofie Bodenheimer and Frieda Dettelbacher are not the only ones from the near relatives to perish. Sofie’s niece Jenny Krämer who had lived in Kassel was murdered in 1942 in Sobibor; her sister Frieda Krämer who lived in Nuernberg was deported the same year to Izbica and subsequently murdered. Both were daughters of Flora Kraemer, nee Dettelbacher, an older sister of Sofie’s.

On September 19, 2012, Gunter Demnig laid a Stumbling Stone in memory of Sofie Bodenheimer.

For remembrances and photos the Stolperstein-Initiative thanks Ellen Cohen, the sole surviving granddaughter of Sofie Bodenheimer, the great-nephew Frank Jacoby-Nelson, the great-niece Margot Karp, and also Lisa Krain who is a descendant of Max Dettelbacher (later Dettelburg), a brother of Sofie Bodenheimer’s.

(24th of April 2022 kmr/ec)

Leave a Reply