Marstallstr. 11 (Today the Youth Detention Center)

…Unexpectedly Early Torn from us

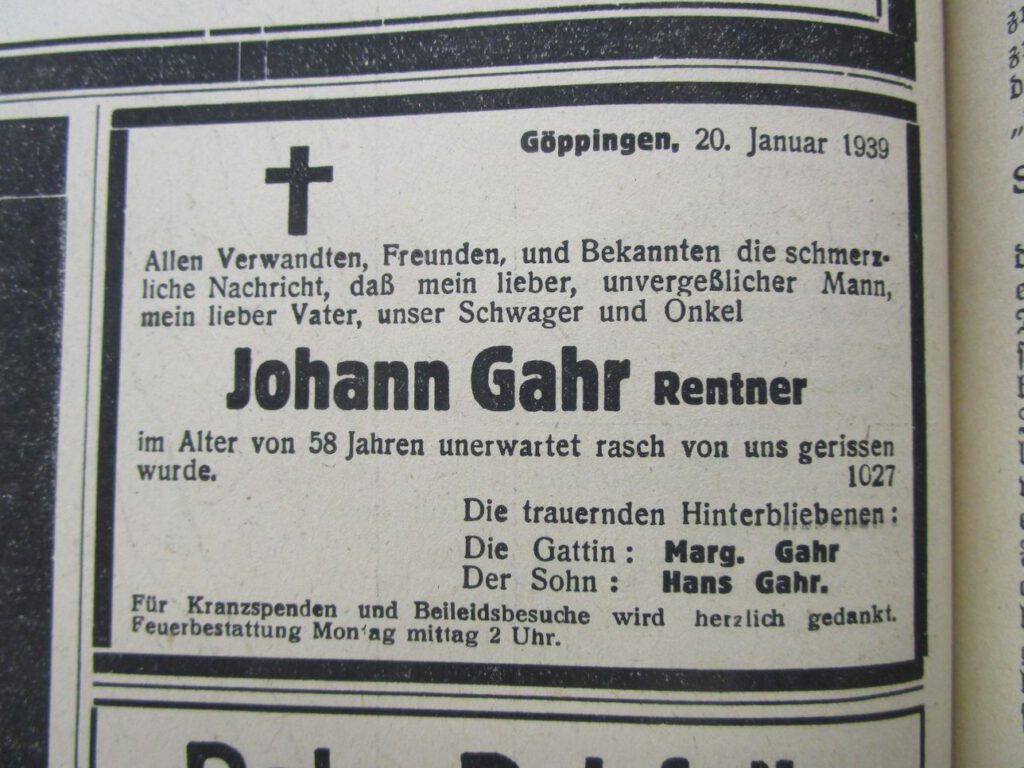

If you leafed through the January 21, 1939, issue of the Göppingen newspaper, ‘The Hohenstaufen,’ you would have come across the announcement of the death of Johann Gahr, a pensioner. The text stated that “at the age of 58 he was unexpectedly torn from us.”

However, this wording did not refer of a fatal disease. Two days earlier Johann Gahr had been arrested and transported to the Göppingen County jail. The preliminary charge against him was high treason. But it never came to a trial because by the next day he was already dead. Suicide by hanging was given as the official cause of death.

In 1946, Johann Gahr’s widow Margarete wrote to the Office for Restitution: “On January 20, 1939, I received word from the jail that my husband had committed suicide but which I found hard to believe. Other Göppingen citizens did not believe this explanation either.” Mrs. Gahr listed several indications which led her to this conclusion: “In my opinion, my husband was murdered during the interrogation.” Sonja Mϋller, the granddaughter of Margarete and Johann Gahr, remembers that her grandmother made these observations: Johann Gahr’s corpse showed marks of blows to the temple. Had Gahr been tortured to death at the Göppingen jail? There are many signs that point to murder, but to this day there is no absolute confirmation of this.

In 1945 the Prosecutor’s Office did not appear to be interested in resolving this case.

The History Leading Up to the Arrest

Oskar Schneider, a man from Donzdorf, was instrumental in the arrest of Johann Gahr and four other anti-fascists. Schneider lived in poverty but must have had a strong desire to feel important. Therefore he often interfered in local issues. Although he was not a member of the KPD [Communist Party of Germany], but he seemed to have moved in those circles and knew several party members. His brother-in-law, a Stuttgart SA member, also knew about this connection. He gave a tip to Stuttgart Gestapo official Ludwig Thumm with the suggestion that he might want to visit Oskar Schneider, which he did in the spring of 1936.

Thumm presented Schneider with a list of about 50 KPD and SPD [Social Democratic Party of Germany] party members and supporters in the Oberamt (county) Göppingen and asked him if he, Schneider, could give a report about these persons to the Gestapo. After thinking it over, Oskar Schneider was willing to do so. It is hard to judge the reason for his motive. Even though he was promised and received financial compensation, it is likely that his desire to feel important played a role in his decision. Schneider attempted to excuse his behavior in front of a denazification tribunal after the war: supposedly he was pressured by being threatened with the loss of the custody of his children.

This testimony might actually have been true but cannot be verified through any other sources. According to his own statements, Schneider provided Thumm with 12-15 reports. It doesn’t appear that these reports contained much incriminating information. Nevertheless it is documented that the so-called ‘Brown Book’ was passed along.

This is a document which explained the role of the Nazis in the Reichstag fire. It cannot be ruled out that Schneider himself encouraged the people he implicated to pass it on. Ludwig Thumm collected these denunciations and passed them along to Stuttgart Gestapo-Chief Mussgay. Surprisingly, this did not lead to any immediate prosecution. One can only speculate about the reasons for this, but probably the Gestapo did not trust Schneider.

However, the collected incriminating evidence was turned over in 1938 to Strehle, Ludwig Thumm’s deputy, who ordered the arrest of five antifascists in Oberamt [county] Göppingen on January 19, 1939: Albert Geiger and Georg Gänzle from Donzdorf, Wilhelm Geiger and Karl Reichert from Sϋssen, and also Johann Gahr in Göppingen.

The fate of Karl Reichert is known: at first he was held for nine months at Welzheim concentration camp and then sentenced to one year four months in prison for “Planning to commit high treason, reading and distributing of the ‘Brown Books’.” Since Johann Gahr was accused of the same crimes, ‘under normal circumstances’ he could have expected a similar sentence, but the Nazi regime was known to be arbitrary with its punishments. The fate of the other men who were arrested at the same time is unknown, but at least they did not die while they were incarcerated. During the denazification tribunals, Johann Gahr’s death was not discussed in connection with Schneider.

The Gahrs – a Communist Family

(from left)

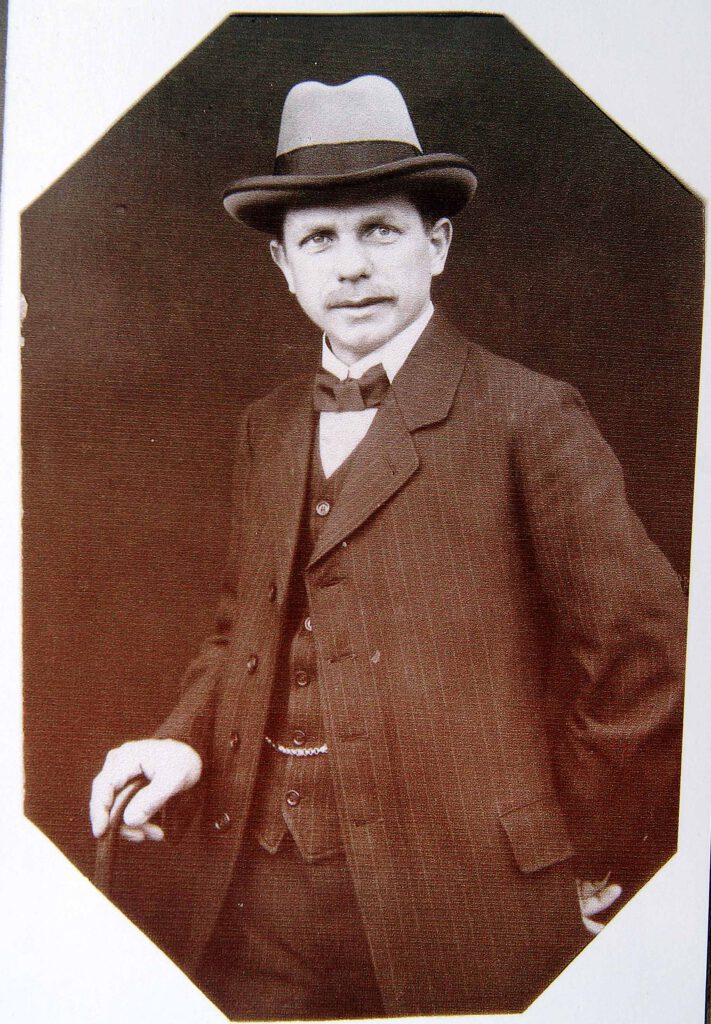

Johann Gahr, born in 1880 in Bayreuth, was an adventurer when he was young. He apparently had not yet developed a political conscience because he and two other young men from Bayreuth volunteered for the Royal Bavarian Regiment which was involved in the bloody suppression of the ‘Boxer-Rebellion’ in China. That means that when Johann Gahr was 20 years old he was in the service of the Colonial powers. He remained in China for another year after the end of the colonial war and didn’t return to Bayreuth until 1903.

Four years later, Johann Gahr, who was a Protestant, married the Catholic Margarete Krug, who was six years his junior. Their son Christian was born prior to their marriage. Their son Hans was also born in Bayreuth, however their youngest child, their daughter Margarete, was born in 1915 in Göppingen, since their family had moved to Wϋrttemberg in 1915.

Even though some ‘minor’ convictions for inflicting bodily harm and gross misdemeanor were recorded during his ‘naturalization’ in 1912, this did not keep him from being declared a ‘Göppinger’.

The Gahr family resided first at Jahnstrasse, later at Middle Karlstrasse. Johann, a shoemaker by trade, worked at first as a foundry worker in Göppingen, then later at the Faurndau shoe factory. Did he first come into contact with the political workers movement while he was working there? It is known that his wife Margarete joined the SPD party in 1911, and it can be assumed that Johann also became a party member at that time. At his place of work he was promoted to shop steward – that means he became a member of the workers council. His granddaughter remembers that from that time on “Politics was very important to the family.”

1914: The members of the European workers movement betrayed the ideals of internationalism and allowed themselves to be incited against each other and get drawn into the war. Johann Gahr, 34 years old, could not avoid becoming involved in the butchery [of World War I]. This would have serious consequences for him. He became an invalid who was 60% disabled and needed a cane to walk. He was not able to work in a factory any longer, and that is when he decided to go back to the trade he was trained in – that of a shoemaker. At least the Gahrs had saved enough money to purchase a small house at Lange Strasse 5 in 1919.

The store and sales area was rented out to a milk and cheese merchant, and Margarete worked there. Johann had his shoe repair business in the back yard, and the family lived in the 64 square meters [689 square feet] apartment on the second floor. Poverty and frugality shaped their lives: Margarete Gahr had to hunt for the best deals and often shopped at Jewish stores because she didn’t want to barter, which sometimes was embarrassing to her husband. The family’s depressing way of life reached a low point when their son Christian died of tuberculosis at the age of 25.

The Gahrs changed their political alliance after the end of the war. Johann and Margarete became members of the KPD [Communist Party], and in 1920 they were instrumental in forming the Göppingen chapter. Until it was banned in 1933, the Göppingen KPD had between 150 and 200 members, but this number fluctuated due to the constantly changing direction at the national level of the party.

Margarete and Johann Gahr took over official duties which must have taken up any free time they might have had. The family was also active in party-related organizations such as the ‘Red Frontline Warriors Group’. The existence of these groups points especially to the newly formed opponents of the workers movement: National Socialism.

The ‘Battle at the Walfischkeller’

During the first few years following the end of World War I, the Nazis did not find much resonance and support in Göppingen. Therefore they wanted to prove their superiority over ‘red’ Göppingen. In December 1922, an armed gang, among them Rudolf Hess, who later became the ‘Fϋhrer’s Deputy’, arrived from Munich. Days in advance, the local Nazi group had put up posters and advertised in the newspaper that a meeting would take place in the ‘Apostle Hall’. The stipulation that ‘Jews will not be admitted’ served as a special provocation. Betty Heimann and Theodor Mayer, both members of Göppingen’s Jewish community, were observed taking down the discriminatory Nazi posters.

The Göppingen trade unions as well as the Communist Party called for workers to protest against the Nazi parade and gathering. When the innkeeper/owner of the Apostle Hall heard about this, he changed his mind and refused to have the Nazis use his facilities for their meeting. Therefore the Nazis, who had already arrived in Göppingen and displayed a show of military strength, had to find another location for their meeting and tried to do so at the ‘Walfischkeller’, a restaurant and inn on the Southside of the railroad tracks. Göppingen’s workers and Jewish citizens saw to it that the Nazis were not able to find a forum for their anti-Semitic hate campaign by blocking access to the Jebenhausen bridge. It came down to hand-to-hand confrontations including firearms, and the day went down in city and state history as ‘The Battle at the Walfischkeller’. The name ‘Gahr’ appears several times in the police reports of this day. It appears that Johann Gahr was instrumental in coordinating the workers’ resistance and that he was a spokesperson with whom the police tried to talk.

Johann Gahr left further imprints in City history, for example as one of the organizers of a march of unemployed workers (not approved by authorities), which attracted 400 participants on July 15, 1931. The result was that 17 people were arrested, and Johann Gahr was jailed for two weeks, Margarete for seven days. It would appear that this was a minor incident without serious consequences.

Only in retrospect does a name carry terrible significance: Gottlieb Hering was the name of the Göppingen Kriminaloberkommisar [chief of detectives] who testified as a witness against Gahr and his co-defendants. Hering was a member of the SPD and was known as a ‘Nazi devourer’ during the time of the [Weimar] Republic. However, when the Nazis came to power, he feared for his position and offered his services to them successfully. In August 1942, the ‘little’ Göppingen policeman was appointed commandant of the Belzec extermination camp, and his ‘career’ as mass murderer continued until the end of the Nazi regime, but this fact was never discussed in Göppingen.

During the 1930s, not only protest against poverty and unemployment defined the political life of the Gahrs, but also the confrontation with the Nazis who were gaining in strength and power. He challenged a Nazi speaker to a debate in 1931, and his name was the signatory on an anti-fascist leaflet.

Under the Reign of the Nazis

In March 1933, the Gahrs were arrested by the Nazis and taken into ‘protective custody’. Johann Gahr was taken to the Heuberg concentration camp near Stetten am Kalten Markt. Margarete was ‘picked up’ on March 15 and after being imprisoned in the women´s prisons in Ulm and Stuttgart she was taken to the womens prison in Gotteszell / Schwäbisch Gmϋnd and imprisoned there until January 21, 1934.

After this extreme intimidation which was followed by constant surveillance, the Gahrs initially seem to have lost their strength and opportunity for resistance. Besides, they were dependent on the good will of the Nazi city administration when they started construction of a two-family house in the suburban Göppingen district of ‘Galgenberg’ in July 1939. The reason why the completion of their building project was delayed until the beginning of 1938 apparently was harassment by the building authorities.

At the beginning of 1939, a few days before the murder of her father, their unmarried daughter Margarete emigrated to Chicago in the USA. This would be a final farewell as she would never see her father again.

Revenge for the ‘Battle’ of 1922?

Walter Lang, the former Göppingen district archaeologist, was the first to suspect a connection between the ‘Battle at Walfischkeller’ and Johann Gahr’s death. He found out that Johann Baptist, Göppingen’s Nazi Kreisleiter [district leader], requested in 1935 to see the police records of the ‘Battle’ of 1922. Did the head of the Göppingen Nazis try to obtain a detailed picture of Gahr’s involvement? Did the Nazis try to find, and actually found the grounds for taking such cruel revenge on Gahr?

After 1945 there were only hesitant attempts made to investigate the fate of Johann Gahr. In November 1949 the Göppingen district court wrote to the State Office for Restitution: “It should be mentioned that the Göppingen Department of Criminal Investigation is currently looking into the circumstances surrounding the death of Johann Gahr. During the hearing on this case, then Justizoberwachtmeister [chief bailiff] and now retired Mr. Keckeisen made statements that were later turned to be untrue. During the summer of that year, the above mentioned Justizoberwachtmeister committed suicide.” The findings of these investigations were not documented; a trial did not take place.

Margarete Gahr’s Path of Suffering

As far as we know, she was the only woman from Göppingen, who had to go through the hell of concentration camps because she was a communist. On September 1, 1939, she was once again taken into ‘protective custody’ in Stuttgart. After three months she was deported to Ravensbrϋck concentration camp where she survived as a Revierarbeiterin [camp hospital worker] – if you can even call this ‘life’ in a concentration camp. She remained under the boot of the Nazis for 77 months and 26 days.

However, they did not succeed in dissuading Margarete from her political convictions. After her liberation she was even more convinced that Socialism was the only form of government that could make life humane and peaceful.

In October 1945 she already showed interest in the anti-fascist womens committees which in 1947 consolidated into the Democratic Womens Association of Germany, and in which she remained a member until it was banned in 1949. During the first local elections in Göppingen in 1946, Margarete Gahr ran as a candidate for the KPD [Communist Party] but was not elected.

After the KPD was banned in 1956, the Deutsche Friedensunion, the DFU [German Freedom Union] was founded in Stuttgart in 1960 which joined together the communist and socialist factions to the left of the SPD. Margarete found her political home in the DFU until it was dissolved in 1980.

It can be taken for granted that she also was a member of the ‘Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes’ (VVN) [Union of Victims of Prosecution by the Nazi Regime] because she received legal assistance in her efforts to get reparation for the physical and mental damages she suffered during her long imprisonment in concentration camps. Only after lengthy negotiations did the German government agree to pay a compensation for the tortures she had suffered.

At least she was awarded a survivors pension in which the State admitted indirectly that Johann Gahr had been murdered by the Nazis. Her pension notification of February 26, 1951, states: “Johann Gahr, your husband, was persecuted by the National Socialist regime and died on January 20, 1939. The cause of death was directly related to this persecution.”

Margarete Gahr lived in her house in Göppingen until 1955; she then moved in with her son Hans and granddaughter Sonja at their residence near Rosenheim, where she died in 1969 at the age of 83.

The Stumbling Stone for Johann Gahr was laid in front of the Marstall, which today houses a youth detention center.

The Initiative Stolpersteine organization wanted to take into consideration the place where Gahr had died. Gunter Demnig understood this and made an exception when he laid the Stumbling Stone there on February 15, 2008, instead of the Gahr residence.

Mrs. Sonja Mϋller, the granddaughter of Johann and Margarete Gahr, and her husband participated in the laying of the Stumbling Stone.

We would like to thank Mrs. Mϋller for the information and photos which she provided.

(4th of Jan. 2017 kmr / ir)

This is a very important and informative article on theses courageous Communists who resisted the nazis as long as they could and then suffered the fate of all who stood against the Hitler regime. Johann was ultimately murdered and the amazing Margarete survived concentration camps and always held to her political position. An outstanding couple.

I have just explored this site because my late mother Judith Horsley was formerly Elfriede Salinger, daughter of Albert and Milda Salinger. He was a dentist in Goppingen until the family moved to Berlin later in the 1930s